Lending Their Voices to the Call for Cancer Research Funding

Each year, the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) holds Early-career Hill Day, bringing a group of AACR Associate members to Washington, D.C., to advocate for strong funding for cancer research and biomedical science. Along with representatives of the AACR’s Science Policy and Government Affairs office, they meet with lawmakers and Congressional staff members, urging the lawmakers to vote for continued robust funding for the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and National Cancer Institute.

We’re delighted to have guest posts from two of the Associate members who joined the AACR on Capitol Hill on February 27 and 28. Brittany Avin and Francis Enane brought unique approaches to the discussion of why continued funding is crucial in the quest to end cancer.

The power of a voice

By Brittany Avin

PhD candidate, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine

Ever since I lost my physical voice at the age of 13, I have tried to never take for granted the power a voice holds. I lost my voice due to cancer that spread to the nerve feeding my vocal cord. Ultimately, I regained normal vocal function through an implant, and my battle against cancer fueled my life’s mission to fight the disease. I became a cancer researcher, currently working toward my PhD at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and researching the same type of cancer I was diagnosed with over a decade ago.

As a patient and a researcher, I see the dire need for cancer research funding. As a patient, I know the critical need for better, less-toxic treatments, early detection, and prognostic biomarkers. As a researcher, I know the struggles of wanting to fulfill that need, but being constrained due to lack of grant money.

At one point during my PhD work, my lab was between R01 grants, the standard independent grants given by the NIH. We had to decide between necessary experiments, because we didn’t have enough money to do all that was needed. It not only impeded my timeline for productivity as an early-career scientist, but potentially cost time in helping patients.

As a cancer survivor, I participated in many lobby days with the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network. This year, I was ecstatic to be selected to participate in the Fourth AACR Early-career Hill Day on February 27 and 28, this time as a cancer researcher. I joined 15 other early-career investigators and AACR staff in a full schedule of meetings. My group met with legislative staff from the offices of U.S. Senators Ben Cardin (D-Maryland), Chris Van Hollen (D-Maryland), and Robert Casey (D-Pennsylvania), as well as U.S. Representatives Elijah Cummings (D-Maryland), Andy Harris (R-Maryland), Brendan Boyle (D-Pennsylvania), Brian Fitzpatrick (R-Pennsylvania), and Dwight Evans (D-Pennsylvania).

In our meetings, we expressed appreciation for providing a $2 billion increase for the NIH in fiscal year 2019, and for enacting the spending bill on time. We also asked for a two-year, bipartisan budget agreement that lifts the caps on nondefense, discretionary spending. Also, we requested that lawmakers allocate $41.6 billion (a $2.5 billion increase) to the NIH in fiscal year 2020.

During the meetings, I was able to tell my personal story as a survivor and researcher. As scientists, we can live in a jargon-filled bubble, speaking technical language in labs and at conferences. Our ability to continue our research depends upon us being able to communicate to a lay audience, and to lawmakers, what we work on and how our federal funding is beneficial for citizens. We are the future of cancer research, and we must protect and increase our ability to do lifesaving work.

We need to use our voice as a scientific community to advocate for robust, sustained, and predictable research funding for the NIH. It was an honor to use my voice as an early-career cancer researcher, and a survivor, to share this important message.

The need for funding transcends parties and ideologies

By Francis Enane, PhD

Post-doctoral researcher at Indiana University School of Medicine

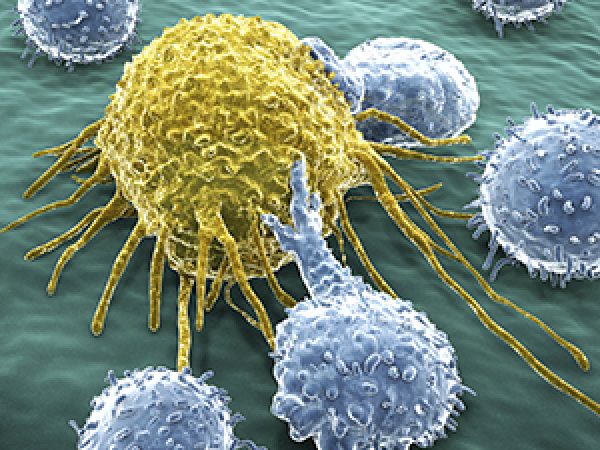

Cancer. It’s arguably one of the most feared diseases in the world, with devastating effects that are felt across the oceans. Encouragingly, progress has been made in the last decade, leading to a 26 percent decline in cancer deaths – approximately 2.4 million lives saved – thanks to research funded through the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

You might wonder, what is the cost of studying cancer? As a young investigator, this cost frequently perplexes me as I peruse funding programs to guide my research and training.

For the NIH to distribute its funds to researchers, it relies on a budget appropriated by Congress and the White House. As expected, priorities change with each new presidential administration and Congress. Yet biomedical funding that is robust, predictable, and sustained is crucial in the quest to find cures for diseases like cancer. Perhaps our leaders need reminders and education on the importance of consistent funding increases.

The opportunity to forge a connection between politicians and scientists motivated me to participate in the 2019 AACR Early-career Hill Day. Along with 15 colleagues, we had the opportunity to ask congressional leaders to work in bipartisan fashion and with the White House to reach a two-year budget agreement that lifts the caps on nondefense, discretionary spending currently in place due to the Budget Control Act of 2011. We also asked Congress to provide a $41.6 billion NIH budget for fiscal year 2020.

Divided into various groups, we blitzed through meetings with more than 60 congressional offices from both the Senate and the House, aiming to cover multiple geographic regions and congressional districts. My group met with leaders and/or staffers from Indiana and Illinois. I discussed my experiences as a translational researcher focused on developing new therapies for treatment-resistant solid tumors. I talked about the emotions and difficulties of reading consent forms to a patient awaiting surgery, promising that providing a small portion of their tumor could lead to therapies that might help millions of other patients. We talked about how keeping this promise is something researchers hold dear to our hearts, but we can only do it with consistent, multi-year NIH funding.

I urged leaders that a vote to increase NIH funding is a vote that saves lives, develops new drugs, generates new companies and technologies, and potentially solves our medical problems. Lastly, I discussed that while political ideologies frequently change, human diseases affect us all regardless of our red and blue state status, and regardless of our wealth or poverty. World-class cures should be accessible to all, and by providing the NIH with the financial resources they need, Congress can make those cures achievable.

The mood on Capitol Hill was collegial, with bipartisan agreement on the importance of NIH funding. We heard encouraging statements from many offices, including that of Republican Senator Todd Young of Indiana, who said, “More money for the NIH is great for the country.” Many of the congressional leaders were heavily involved in health care issues, including Sen. Richard Durbin (D-Illinois), who was drafting a proposal to increase NIH funding by $2.7 billion for fiscal year 2020. We thanked the leaders for their support and encouraged them to continue this momentum for years to come.