The Cost of Cancer Disparities

The Eighth AACR Conference on the Science of Cancer Health Disparities in Racial/Ethnic Minorities and the Medically Underserved, held Nov. 13-16 in Atlanta, continued to shine light on the disparities that exist across many types of cancer. On Wednesday, Nov. 18 from 3 to 4 p.m. ET, we’ll be participating in a Twitter chat hosted by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) focusing on cancer health disparities; you can join us by using the hashtag #CancerDisparities.

The AACR’s disparities conference covered a wide array of issues this year, from the biological factors that make some racial and ethnic groups especially prone to certain types of cancer, to intriguing new ways to improve prevention and detection. Douglas Lowy, MD, acting director of the NCI, delivered the keynote address, titled “Understanding and Overcoming Cancer Disparities in the U.S. and Abroad.” His presentation is available here.

A few presentations also touched on the economic impact of disparities. On the opening day, S. Yousuf Zafar, MD, associate professor of medicine at Duke Cancer Institute in Durham, N.C., led an educational session called “Disparities/Equity in Oncology Treatment and Prevention: Practice, Policy, and Cost Barriers.” He also discussed what he called the “financial toxicity” of cancer care, while Veena Shankaran, MD, associate professor at the University of Washington School of Medicine, addressed “Financial distress in patients with cancer: Contributing factors and potential solutions.”

Hannah K. Weir, PhD, senior epidemiologist with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

Additionally, Hannah K. Weir, PhD, senior epidemiologist with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, presented her study on how the disparity in one type of cancer – colorectal – takes a heavy economic toll on the nation as a whole.

Colorectal cancer provides an interesting window into health disparities. Just a few decades ago, the disease disproportionately affected white patients, and those with higher socioeconomic status (SES). Over time, as growing awareness led more people to get screened, the gap narrowed and has now reversed itself. Today, African-Americans and members of lower SES communities are more likely to get colorectal cancer, and more likely to die from it. According to the NCI, the nationwide incidence of colorectal cancer is 51.6 cases per 100,000 people; the rate among African-Americans is 62.1 per 100,000 people, and among whites, the rate is 51.2 per 100,000. The death rate nationwide is 19.4 per 100,000 people, compared with 26.7 among African-Americans and 18.9 among whites.

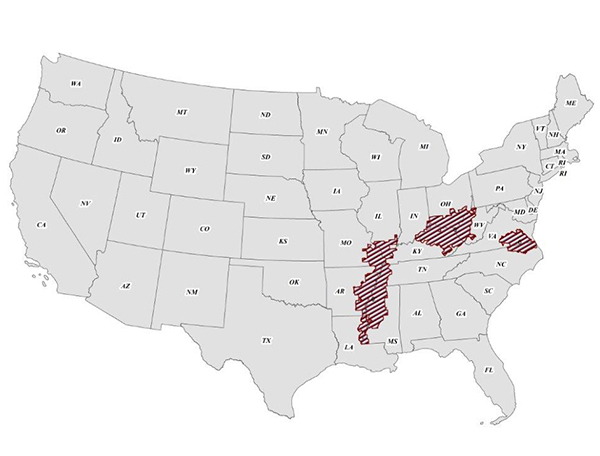

This past summer, the AACR published research on three geographic hot spots where colorectal death rates are much higher than the overall U.S. rates. All three – the Mississippi Delta, west central Appalachia, and eastern Virginia/North Carolina – experience high poverty rates.

This map shows the three “hot spots” identified in the study. Graphic courtesy of the American Cancer Society.

In order to evaluate the economic impact of the colorectal cancer disparity, Weir and her fellow researchers applied the colorectal cancer mortality rate from higher SES communities to lower SES communities and found that 16.8 percent of the deaths in lower SES communities were potentially preventable if the mortality rates had been equal.

Weir determined that eliminating avoidable colorectal cancer deaths would result in $4.2 billion in nationwide productivity gains in men and $2.2 billion in women.

Weir said “productivity gains” reflect wages and salaries, as well as expected financial contributions to family care. They do not include the cost of diagnosis, treatment, and care (although those direct costs have also been well documented in disparities research).

Beyond the dollar figures, Weir’s study showed that in lower SES communities, 194,927 years of potential life were lost due to premature colorectal deaths, compared with 128,812 years of potential life lost in the higher SES communities.

“Those are years in which these people would have been contributing to the financial welfare of their family and their community,” Weir said.

Weir and her fellow researchers said that increasing awareness of colorectal cancer in lower SES communities could help decrease the number of deaths, thereby reducing the economic toll the disease takes.