Highlights from AACR Meeting Focusing on Environmental Carcinogenesis

Decades of research have led to the identification of an increasing number of cancer-causing substances in our environment. These substances, known as environmental carcinogens, can be found anywhere, including in our air, water, food, and workplace.

Despite the progress we have made in identifying and increasing awareness of such carcinogens, experts believe that we have a long way to go before we have fully delineated them and successfully regulated our exposures to reduce cancer incidence. Therefore, methods to better identify all of the carcinogens in our environment, to measure our exposure to them, and to prevent cancer caused by them are areas of active investigation in the field.

Cutting-edge research in these and other areas was presented at the recent AACR conference in Charlotte, North Carolina, titled Environmental Carcinogenesis: Potential Pathway to Cancer Prevention. Topics of discussion included the utilization of biomarkers to measure cumulative carcinogenic exposures, how exposures in the workplace can lead to cancer disparities, and how carcinogenic exposures affect the microbiome.

Here we spotlight four studies presented at the meeting that highlight the breadth of research in the field, in addition to a relevant study recently published in Molecular Cancer Research.

Calculating the cancer-related burden of nitrates in drinking water

Many cancer prevention efforts focus on promoting the consumption of a healthy, well-balanced diet to mitigate cancer risk. Such recommendations include choosing water instead of a sugary beverage, and many Americans rely on tap water for their needs. While drinking water in the U.S. is among the safest in the world, contamination can still occur.

Low levels of nitrates and nitrites, which can occur naturally in our water, do not generally pose a health risk. However, high levels of these compounds can result in adverse outcomes. Water can become contaminated with high levels of nitrates and nitrites from many sources, including fertilizers, septic systems, animal feedlots, industrial waste, and food processing waste. Many epidemiological analyses have evaluated how nitrate ingestion affects health risks, and several studies have found an association between nitrate ingestion from drinking water and increased risk of colorectal cancer.

Alexis Temkin, PhD, from the Environmental Working Group, reported a comprehensive assessment of nitrate exposure from drinking water in the entire United States population. Temkin’s group estimates that 2,300 to 12,594 cases of colorectal, ovarian, thyroid, kidney, and bladder cancers are attributable to nitrate exposure from drinking water per year. According to their analysis, medical expenditures for these cancer cases range from $250 million to $1.5 billion, and the economic cost from lost productivity could potentially range from $1.3 to $6.5 billion.

These results suggest that our exposure to nitrates in drinking water has significant health and financial implications.

A model to assess exposures to multiple environmental carcinogens

Exposure to individual environmental carcinogens can pose a health risk. However, recent data suggest that exposure to multiple environmental carcinogens – such as volatile organic compounds, particulate matter, and heavy metals – may synergistically increase adverse health outcomes.

Terry Hyslop, PhD, from Duke University, proposed a way to model multi-pollutant exposure. Using data from the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), including the National Air Toxics Assessment, Hyslop and colleagues developed a model that informs overall exposure levels to multiple toxins and provides measures of multi-pollutant exposure measured at the census tract level.

Amounts of volatile organic compounds, particulate matter, and heavy metals to which people in the United States are exposed could be stratified into five, two, and four levels, respectively. Hyslop reported that 12 percent of U.S. census tracts are exposed to the highest levels of all three categories of pollutants. While the highest levels of pollutants were often observed in metropolitan regions, such levels were also observed in some rural areas.

Environmental quality may contribute to metastatic breast cancer

The EPA has developed an environmental quality index (EQI) to estimate the overall environmental quality of each county in the country. To do this, the EQI integrates data from air, water, land, built, and sociodemographic environments. Researchers can use the overall environmental quality or the individual component quality data to potentially identify how these can affect health outcomes.

A study presented by Larisa Gearhart-Serna, a PhD candidate at Duke University, aimed to identify how environmental quality impacted the incidence of aggressive breast cancer among patients living in North Carolina. Gearhart-Serna and colleagues used cancer case information from the North Carolina Central Cancer Registry from the years 2009-2014 to calculate the odds of having ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), a noninvasive breast cancer, versus metastatic breast cancer, based on the environmental quality of the patients’ home counties.

Gearhart-Serna reported that environmental quality influenced the chances of having metastatic breast cancer compared with DCIS. Among breast cancer patients living in a county with the worst land environmental quality, the risk of having metastatic disease was 5 percent greater than having DCIS; this trend was further strengthened in more rural areas. Among breast cancer patients living in a county with the worst sociodemographic environmental quality, the risk of having metastatic disease was 6 percent greater than having DCIS; this trend was not affected by urban or rural residency.

The results from this study suggest that environmental quality is associated with metastatic breast cancer, and that rural-urban residency may increase these trends in certain environments.

Monitoring first responders’ exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

Due to the inherent nature of their work, first responders, especially firefighters, are exposed to a variety of potentially carcinogenic substances. One such class of potentially carcinogenic compounds is polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which are present in motor vehicle exhaust, fumes from asphalt roads, charred meats, and other sources.

Many PAHs are described as “possible” or “probable” human carcinogens; while many PAHs have been shown to be carcinogenic in animal models, there is not sufficient evidence to definitively understand whether these compounds cause cancer in humans. Despite the lack of complete data, it is important to understand who is exposed to these chemicals, and what amount of PAH exposure they are subjected to.

A study presented by Alberto Caban-Martinez, PhD, DO, MPH, from the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, investigated the occupational exposure of firefighters to PAHs. To assess their exposures to these “possible” or “probable” carcinogens, firefighters throughout South Florida wore silicone-based wristbands for a 24-hour work shift. The wristbands were then analyzed for the presence of PAHs.

Of the 24 wristbands evaluated, all of them contained naphthalene, a possible human carcinogen. Furthermore, 88 percent of wristbands contained benzo[b]fluoranthene, 79 percent contained chrysene, and 50 percent contained benzo[j]fluoranthene, all of which may be human carcinogens.

While preliminary, these results suggest that passive personal sampling devices could be utilized to monitor first responders’ exposure to potential carcinogens.

Increased risk of prostate cancer among World Trade Center responders may be caused by inflammatory cascade

Rescue and recovery workers who responded to the terrorist attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, have shown an increased incidence of many adverse health outcomes, including aerodigestive disorders, musculoskeletal disorders, mental health conditions, and many cancers. The James Zadroga 9/11 Health and Compensation Act of 2010 established the World Trade Center Health Program, which provides medical monitoring and treatment for survivors and responders of the attacks. Over 50 types of cancer are covered by this program, including prostate cancer.

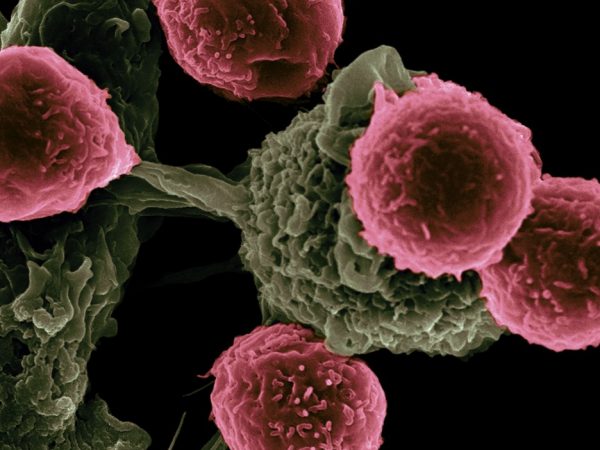

To help elucidate a mechanism for the increased incidence of prostate cancer among this patient population, a study recently published in Molecular Cancer Research compared archival prostate cancer samples by analyzing the differential patterns of gene expression between 15 World Trade Center responders and 14 unexposed individuals. They found that prostate tumors taken from the responders had an upregulation of genes involved in immune modulation and cell death compared to tumors from unexposed patients.

Furthermore, cell-type enrichment analyses found that several pro-inflammatory cell types were upregulated in prostate samples taken from the responders compared to prostate samples isolated from unexposed patients.

“Our results suggest that inflammatory mechanisms are activated in the prostate after exposure to World Trade Center dust, which may give rise to chronic inflammation and contribute to prostate cancer progression,” said co-first author William Oh, MD, in an AACR press release.

What’s next for the field of environmental carcinogenesis?

We are continuing to delineate environmental carcinogens and how their exposure may affect our overall health. To date, the International Agency for Research on Cancer has identified 120 agents to be carcinogenic to humans, including chemical substances such as mustard gas, physical agents like silica dust, and complex/mixed agents such as outdoor air pollution. As highlighted at the meeting, the identification and definition of environmental carcinogens is an area of active research.