Burning Issues in Skin Cancer Prevention

With warm weather finally here, bringing more people outdoors, it is important to remember that many cases of skin cancer, including 90 percent of cases of melanoma—the most deadly form of the disease—could be avoided by reducing or eliminating exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun, sunlamps, sunbeds, and tanning booths. Despite this knowledge, skin cancer remains the most commonly diagnosed type of cancer in the United States, with nearly 5 million U.S. men and women treated for the disease each year.

To encourage sun safety awareness, remind people to protect their skin while outside, and help reduce rising rates of skin cancer from overexposure to UV radiation from the sun the National Council on Skin Cancer Prevention designates the Friday before Memorial Day as “Don’t Fry Day.”

Here, I discuss why we need initiatives like “Don’t Fry Day.” National initiatives are bolstered by research, and research presented at the recent AACR Annual Meeting 2016 opens the door to future advances in skin cancer prevention.

Here, I discuss why we need initiatives like “Don’t Fry Day.” National initiatives are bolstered by research, and research presented at the recent AACR Annual Meeting 2016 opens the door to future advances in skin cancer prevention.

The Growing Burden of Skin Cancer

Worryingly, as we’ve highlighted previously on this blog, the incidence rate for melanoma has been rising in the United States for more than three decades. Moreover, if current trends continue, researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) anticipate that the number of new U.S. melanoma cases diagnosed each year will rise dramatically in the coming decades, increasing from 65,647 in 2011 to 112,000 in 2030.

Worryingly, as we’ve highlighted previously on this blog, the incidence rate for melanoma has been rising in the United States for more than three decades. Moreover, if current trends continue, researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) anticipate that the number of new U.S. melanoma cases diagnosed each year will rise dramatically in the coming decades, increasing from 65,647 in 2011 to 112,000 in 2030.

Fortunately, the same researchers also predict that nationwide implementation of a comprehensive, community-wide skin cancer prevention program, like the highly successful SunSmart program in Victoria, Australia, could prevent about 230,000 melanoma cases between 2020 and 2030.

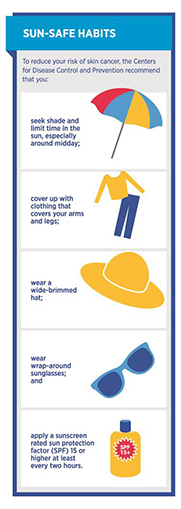

The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Skin Cancer in July 2014 outlined five strategic goals to promote skin cancer prevention in the United States through education, public policy, and research. Among the educational messages emphasized in the report is that everyone needs to adopt as many sun-safe habits as possible, including wearing a hat, sunglasses, and other protective clothing; seeking shade; and using a broad-spectrum sunscreen with a sun protection factor (SPF) of 15 or higher.

Research Holds the Key to New Advances in Skin Cancer Prevention

Sunscreens are a central component of every organization’s sun-safety recommendations, including those put forth by the National Council on Skin Cancer Prevention, the CDC, and the Surgeon General. Sunscreens work by absorbing and/or reflecting UV radiation from the sun. Experts recommend broad-spectrum sunscreens because they have ingredients active against each of the two types of UV radiation that cause skin cancer—UVA and UVB.

However, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) warns that although using broad-spectrum sunscreen is an important part of skin cancer prevention, it cannot fully protect the skin from the damaging effects of UV radiation from the sun.

Therefore, in addition to identifying ways to increase use of current skin cancer prevention approaches, researchers are interested in improving the effectiveness of sunscreens and developing new, more effective approaches to skin cancer prevention.

Data presented at the recent AACR Annual Meeting 2016 in New Orleans, which showed that application of sun protection factor 30 (SPF30) sunscreen prior to exposure to UVB light delayed melanoma onset in a mouse model of the disease, suggest that researchers now have a mouse model to use to identify new, more effective melanoma-preventing agents.

The research team, led by Christin Burd, PhD, an assistant professor in the Department of Molecular Genetics and the Department of Molecular Virology, Immunology & Medical Genetics at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center Comprehensive Cancer Center – Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute, used genetically engineered mice that spontaneously develop melanoma about 26 weeks after the chemical 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4OHT) is applied to the skin.

Burd and Andrea Holderbaum, a senior undergraduate biology major working in Burd’s laboratory, found that if they exposed the genetically engineered mice to a single dose of UVB light one day after applying 4OHT to the skin, melanomas appeared much more rapidly, and there were many more tumors. Applying any of a number of SPF30 sunscreens that contained a range of UV-blocking agents to the mice prior to exposure to the UVB delayed melanoma onset and reduced tumor incidence.

“Sunscreens are known to prevent skin from burning when exposed to UV sunlight, which is a major risk factor for melanoma,” said Burd in a news release. “However, it has not been possible to test whether sunscreens prevent melanoma, because these are generally manufactured as cosmetics and tested in human volunteers or synthetic skin models.”

Burd explained that the model has some limitations, which she hopes she and her colleagues can overcome, but said, “We have developed a mouse model that allows us to test the ability of a sunscreen to not only prevent burns but also to prevent melanoma. This is a remarkable accomplishment. We hope that this model will lead to breakthroughs in melanoma prevention.”

Models such as that developed by Burd and colleagues are sorely needed because the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which has not approved any new sunscreen active ingredients for more than a decade, recently rejected eight applications on the grounds that it needed more data establishing the safety and effectiveness of the agents.

In addition, a recent study by Consumer Reports found that 43 percent of the 60 lotions, sprays, and sticks labeled SPF 30 or higher failed to live up to the SPF claims on the label, further highlighting the need for more research into new approaches to skin cancer prevention.