Building Better Cancer CAR T-Cell Immunotherapy

Researchers are working to expand CAR T-cell therapy successes against blood cancers to solid tumors.

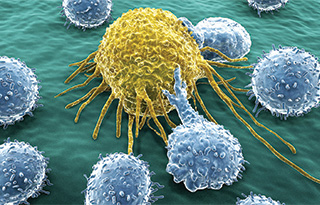

As scientists have learned how to enlist the body’s immune system to fight cancer, several primary strategies have emerged. One approach, called CAR T-cell therapy, has shown promising results with blood cancers. Recently, a pair of research teams took steps toward making this form of cancer immunotherapy effective against solid tumors, too.

The technology behind CAR T-cell therapy is called adoptive T-cell transfer. This process involves removing T cells from a patient’s body and genetically modifying them to express a CAR – a chimeric antigen receptor – so that the modified T cell can then be directed toward a protein present on a tumor cell.

Once “equipped,” the modified T cells are reintroduced to the body, where they multiply and attack cancer cells.

So far, CAR T-cell clinical trials have focused on B-cell malignancies including leukemia and lymphoma. They’ve been very promising, with up to 90 percent of patients experiencing a complete response. However, the CAR T cells tested in these trials cannot distinguish cancerous cells from normal cells. For B-cell malignancies, this is not a problem, because a patient’s immune system can function even when normal B cells are depleted.

But if the same technology were deployed against a solid tumor, it would most likely damage vital organs. The target proteins present on the cancer cells of solid tumors are also present on normal cells, and research has indicated that serious side effects could result if CAR T cells began attacking the normal cells.

So, researchers had set out to engineer T cells that can selectively target cancer cells and spare normal cells. Recently, two different teams of researchers have reported some progress in this effort.

The two teams published their data independently in Cancer Research, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR).

At the University of Pennsylvania’s Abramson Family Cancer Research Institute, researchers in the laboratory of Carl June, MD, focused on a target protein called ErbB2. They hypothesized that lowering the affinity of CAR T cells to ERbB2 could make them only recognize cancer cells that have high levels of ErbB2, while not attacking normal cells, including heart and lung cells, that have low levels of the same protein.

The team engineered a panel of CAR T cells with varying affinity to ErbB2, and set to work experimenting in cell cultures and in animals. Indeed, the low-affinity ErbB2-directed CAR T cells were able to selectively target cancer cells and spare normal cells.

Around the same time, a team at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, led by Laurence Cooper, MD, PhD, set out on a similar challenge.

“The goal – was to make CAR-expressing T cells differentiate friend from foe,” Dr. Cooper explained.

The MD Anderson team chose a different target protein: EGFR, which is present in high quantities in certain brain cancers and in low levels in normal cells, including cells of the skin, kidney and gastrointestinal tissue. Like the Penn researchers, they were able to engineer T cells with low affinity to EGFR to selectively target cancer cells and spare normal ones.

Both studies have proven that safer, more potent CAR T cells may have the potential to benefit patients with solid tumors. It will be exciting to watch the progress in this arena of cancer research.