AACR Disparities Meeting: The Impact of Structural Racism on Breast Cancer Outcomes

Due to advances in screening and treatment, the survival rate for patients with breast cancer has increased in recent decades. However, this progress has not been felt equally across all racial/ethnic groups, as Black women are still 40 percent more likely to die of breast cancer than white women. Black women are also more likely to be diagnosed with more aggressive and more advanced breast cancers, and they are more likely to face hurdles in their treatment, including implicit bias and access to affordable health care.

Understanding the complex factors that contribute to these well-established disparities can shed light on some of the systemic changes needed to address inequities in health care.

At the 14th AACR Conference on the Science of Cancer Health Disparities in Racial/Ethnic Minorities and the Medically Underserved, researchers examined the impact of comorbidities on breast cancer disparities from various perspectives: Gatikrushna Panigrahi, PhD, and Michelle Doose, PhD, MPH, shared research on how comorbidities may impact breast cancer biology and treatment, and Lauren McCullough, PhD, MSPH, and Jasmine Miller-Kleinheinz, PhD, discussed how structural racism in the housing market may explain why Black women are more likely to have these comorbidities in the first place.

Comorbidities may impact tumor biology and quality of care

Comorbidities, such as obesity and diabetes, can limit treatment options and access to clinical trials, and have been suggested to negatively impact outcomes in patients with breast cancer. Since certain comorbidities are more prevalent among Black individuals, researchers have hypothesized that the higher mortality rates observed in Black women with breast cancer may be due, in part, to the impact of these comorbidities on breast cancer biology and treatment.

Consistent with this hypothesis, Panigrahi, who is a researcher at the National Cancer Institute, observed that hyperglycemia and diabetes were associated with increased cell migration in cell models and increased metastases in mice. By analyzing gene expression in patient breast tumors, he found that tumors from patients who had diabetes had higher expression of genes associated with metastasis and mesenchymal phenotype and decreased expression of DNA repair genes. Together, the results indicate that diabetes, a common comorbidity among Black women with breast cancer, may induce changes to gene expression that promote metastasis, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, and DNA damage, all of which may increase a tumor’s aggressiveness.

Beyond biological impacts, comorbidities may also adversely affect the quality of care a patient receives, according to Doose, a postdoctoral fellow at the National Cancer Institute. Doose reasoned that having multiple comorbidities means patients may receive care for their various diagnoses from several different physicians, potentially from multiple health care settings. This care fragmentation could result in a lack of communication between health care providers with adverse effects on patient care.

“When patient care activities are not organized, or patient care information is not coordinated and shared among all team members, then the care is fragmented,” she said. “There are real consequences of care fragmentation—monetary costs, patient and clinician burden and burnout, and harm to patients due to medical errors that lead to poorer clinical outcome.”

Care fragmentation due to comorbidities may even contribute to the racial/ethnic disparities seen in breast cancer, she suggested.

In her presentation, Doose shared findings from her research examining health care composition and complexity among Black women with breast cancer who had cardiovascular, pulmonary, or metabolic comorbidities. She reported that 79 percent of the patients included in the study experienced care fragmentation, which was defined as receiving care in multiple health care systems. Furthermore, patients with multiple comorbidities were more likely to have a health care team with greater complexity, meaning that physicians from separate disciplines were involved in their care.

“Care fragmentation is prevalent and may exacerbate cancer care disparities,” said Doose. “This illustrates the need for a better understanding of the care fragmentation challenges across diverse practice settings but also within the same health care systems.

“If we want to address cancer health disparities, we need to understand and address care fragmentation from a health care team and health care system perspective across all stages of cancer.”

The studies presented by Panigrahi and Doose provide potential explanations for how common comorbidities might worsen outcomes and exacerbate disparities for Black patients with breast cancer, but they also raise an important question—

Why are Black women more likely to develop these comorbidities?

The social and biological impacts of redlining on comorbidities in Black women

The answer to this question may lie, at least in part, in the longstanding history of racism in the housing market.

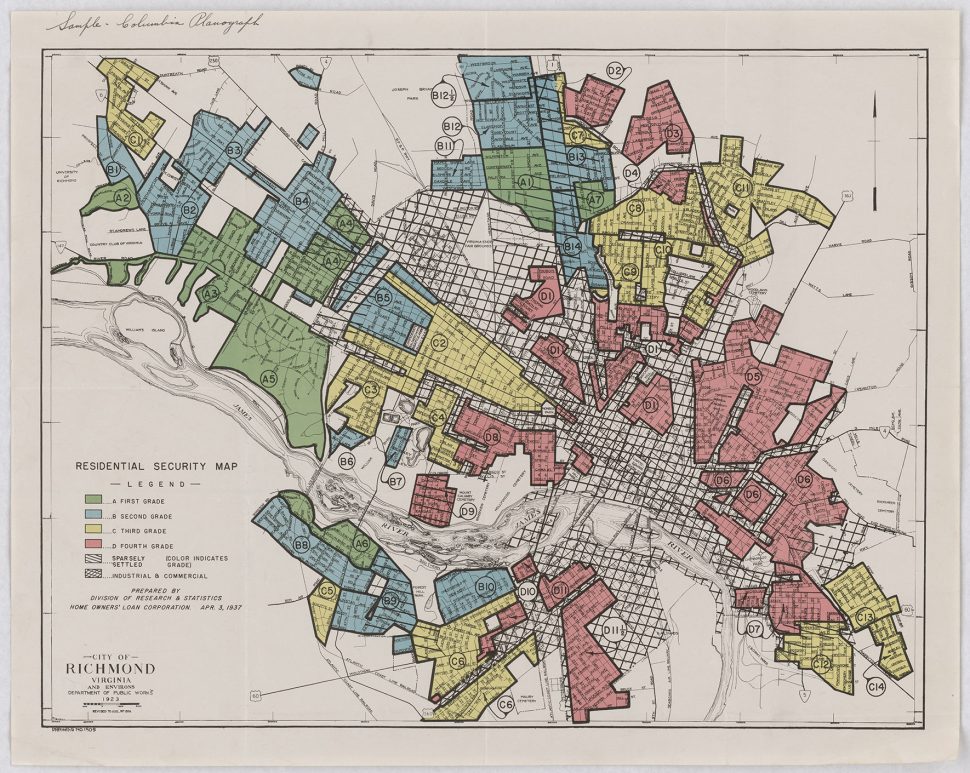

Following the passage of the National Housing Act of 1934, the federal government—ostensibly to help boost the housing market in the aftermath of the Great Depression—issued maps delineating financially “risky” neighborhoods to which mortgage lenders should avoid lending. Unfortunately, the riskiness of each neighborhood was based primarily on its racial makeup, with predominantly Black neighborhoods deemed the riskiest for mortgage lending despite the absence of any evidence that would suggest this to be the case.

This practice, known as “redlining,” led to the systematic denial of mortgages to Black applicants and divestment of resources from predominantly Black areas.

“Banks would not lend to those areas, grocery stores were not built in those areas, parks were not built in those areas,” said McCullough, who is an assistant professor at Emory University.

The repercussions of these actions are still seen today. McCullough and colleagues have shown that historically redlined neighborhoods in Atlanta, many of which continue to have a predominantly Black population, have higher rates of breast cancer mortality today after adjusting for age and cancer stage. Residents of historically redlined neighborhoods also have an elevated risk of late-stage diagnosis, even in neighborhoods with present-day economic privilege, suggesting that factors beyond socioeconomics may contribute to redlining-associated disparities.

“Institutional racism can lead to systematic sorting, or segregation, of people into different types of neighborhoods, which affects access to green spaces, grocery stores, and environmental toxicants,” McCullough explained. She noted that fewer green spaces and grocery stores may limit opportunities for exercise and healthy diets, an idea in line with the finding that residential segregation increases the risk of obesity among Black women.

“We have to think of structural factors as a fundamental cause of disparities,” she added. “These systemic issues have created neighborhoods and cultures that facilitate comorbidities and obesity.”

The lasting consequences of redlining may also induce biological changes that promote breast cancer. Miller-Kleinheinz, a postdoctoral fellow in McCullough’s lab, presented data showing that living in a historically redlined neighborhood was associated with increased DNA methylation at 36 sites in the tumor genome. The majority of these sites were within genes implicated in carcinogenic processes, including oncogenic signaling, chronic inflammation, and immune function.

“Our work highlights that structural inequities, such as redlining, have biological consequences,” Miller-Kleinheinz noted. “Future research should further explore the impact of redlining-associated perturbations on breast cancer outcomes.”

Together with the research presented by Panigrahi and Doose, these findings highlight the need to examine breast cancer disparities with a multifaceted approach—one that includes structural racism and its biological and societal consequences. The studies described here suggest that redlining has led to conditions that increase the likelihood that Black women will develop comorbidities, which, in turn, may increase mortality through their effects on breast cancer biology and/or patient care.

So, how could these findings help address racial disparities in breast cancer? For patients who are already dealing with breast cancer and one or more comorbidities, improving care coordination between different health care teams could streamline treatment and reduce errors, suggested Doose. In addition, Panigrahi proposed evaluating therapeutics that target the gene expression changes associated with comorbidities as a potential approach to improve outcomes. On a larger scale, combatting environmental racism by investing in underserved neighborhoods is just one step toward reducing breast cancer mortality for future generations of Black women.