FDA Expands Use of First CAR T-cell Therapy to Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Earlier this week, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved expanding the use of the immunotherapeutic tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah) to include certain patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

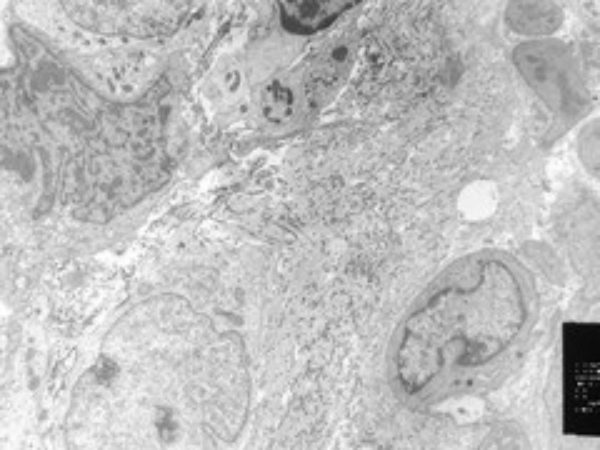

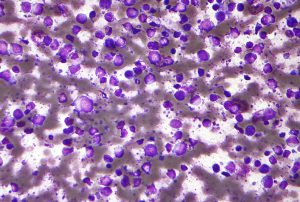

Micrograph of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, the most common type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Image by Nephron, via Wikipedia.

In August 2017, tisagenlecleucel became the first of a revolutionary new type of immunotherapy known as chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T–cell therapy to be approved by the FDA. That approval, which was highlighted in a post on this blog, made tisagenlecleucel a treatment option for children and young adults up to the age of 25 who had a diagnosis of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) that is refractory, meaning that it has not responded to standard treatments, or has relapsed after successful treatment at least twice.

This week’s approval is for the use of tisagenlecleucel as a treatment for adult patients who have large B-cell lymphoma that is refractory to or has relapsed after they have tried two or more types of systemic therapy.

The term large B-cell lymphoma encompasses a number of types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), high grade B-cell lymphoma, and DLBCL arising from follicular lymphoma. DLBCL is the most common of these cancers. In fact, according to the National Cancer Institute, it is the most common type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma diagnosed in the United States, accounting for about 30 percent of new cases of the disease. Thus, it is expected that there will be 22,404 new cases of DLBCL diagnosed in the United States in 2018.

As the name suggests, large B-cell lymphomas arise in immune cells called B cells, which almost always have a protein called CD19 on their surface. CD19 is the target of tisagenlecleucel.

Tisagenlecleucel is not a uniform treatment. As explained in the previous post about the immunotherapeutic on this blog, each patient’s treatment is customized using immune cells called T cells harvested from his or her blood. The harvested T cells are genetically modified to have a new gene that encodes a protein called a CAR, which is why this type of treatment is often referred to as cell-based gene therapy.

After modification, the T cells are expanded in number and then infused back into the patient, where the CAR directs them to CD19-positive large B-cell lymphoma cells and triggers them to attack once they get there.

The approval of tisagenlecleucel for relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma was based on data from the multicenter, phase II JULIET clinical trial. Initial results from the trial, which were presented at a scientific conference in December 2017, showed that after three months of follow-up of 81 patients, 32 percent had complete responses and 6 percent had partial responses. Forty-six of these patients had been followed for an additional three months, and among these patients with six months of follow-up, 30 percent had a complete response and 7 percent had a partial response. Given that most responses were sustained between the time points analyzed, the median duration of response was not calculable.

The researchers reported at the conference that 86 percent of patients who received tisagenlecleucel had grade three or four adverse events, with 58 percent having cytokine-release syndrome and 12 percent having neurological adverse events. These are known adverse events following CAR T-cell therapy. However, they can be life-threatening. Thus, tisagenlecleucel approvals come with a boxed warning for cytokine-release syndrome and neurological toxicities, and the immunotherapeutic is only available through a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy program. This program requires that health care facilities using tisagenlecleucel be specially certified, with staff trained to recognize and manage cytokine-release syndrome and neurologic events.

The new approval makes tisagenlecleucel the second CAR T-cell therapy approved for large B-cell lymphomas. The first, axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta), was approved by the FDA for this use in October 2017. With many new CAR T-cell therapies under development, including some targeting proteins other than CD19 and some designed to be much simpler to manufacture, and many researchers investigating ways to improve the ones that we already have, it is clear that there will be more posts about this new approach to cancer treatment on this blog in the future.