Party with a Purpose Benefits AACR and Supports Lung Cancer Research

After a hiatus caused by the pandemic, Party with a Purpose, a cause-driven gala in Philadelphia that supports cancer research, is back. The American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) was selected as the beneficiary, and funds raised at this year’s event will be dedicated to lung cancer research.

At the gala, to be held on Oct. 30, Party with a Purpose will bestow both philanthropic and scientific awards. Dorothy Giordano and the Hon. Frank Giordano will receive the Humanitarian Award in recognition of their philanthropic contributions.

Corey J. Langer, MD, director of thoracic oncology at the Abramson Cancer Center and professor of medicine at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Perelman School of Medicine, will receive the 2022 Scientific Achievement Award. He has chosen Melina Elpi Marmarelis, MD, MSCE, assistant professor of medicine at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania and medical director of the Penn Mesothelioma and Pleural Disease Program, to receive the 2022 Friends of the AACR Foundation Early Career Investigator Award.

We interviewed Langer and Marmarelis to learn more about their research and the impact of these awards.

How did you decide to focus on lung cancer research?

Langer: When I finished medical school, I was taught that cancer, particularly lung cancer, was an automatic death sentence; it was sort of like Dante’s Inferno—“abandon hope all ye who enter here.” Small cell lung cancer was particularly devastating. During my second rotation as an intern, my attending physician admitted a patient with newly diagnosed, extensive-stage small cell lung cancer. She was very sick, trailing an oxygen tank behind her, and had a large pleural effusion that needed to be drained. The attending physician indicated that she would start chemotherapy that evening and would be readmitted three weeks later for her second cycle of chemotherapy toward the end of my rotation. Based on what I’d been taught in medical school less than one year earlier, I doubted she’d still be alive. After receiving chemotherapy, she came back three weeks later feeling much better; the oxygen tank was gone, her X-rays looked much better. After witnessing the impact therapy had on that patient, I was sold. From that point forward, I had my career set on being an oncologist, and my interaction with that attending, and particularly with small cell lung cancer patients, geared me toward thoracic oncology.

Marmarelis: My decision to focus on lung cancer research has a lot to do with Corey Langer. I came to Penn as a fellow and he was my mentor. I was very interested in immunotherapy, but I didn’t know much about lung cancer and I definitely didn’t appreciate what a big role immunotherapy was playing in lung cancer. But we were seeing some amazing responses in patients and a lot of hope in the clinic, so that really drew me to thoracic oncology.

Dr. Langer, what are the most exciting advancements in immunotherapy for lung cancer, and how have they changed the landscape for patient treatment?

Langer: I was an immunotherapy skeptic. That was colored by our experience in the ‘80s and ‘90s when the therapies that were poised to manipulate the immune system were showing serious toxicity, particularly in thoracic malignancy, with very little benefit. When modern immunotherapy centered on checkpoint inhibition came along, we started seeing activity in lung cancer and other malignancies. Some patients experienced phenomenal responses that we could not have predicted a priori, with very little toxicity. It became a juggernaut. We’re seeing five-year survival now in patients with metastatic disease, after disease progression on standard treatments. This is totally unprecedented. Five to 10 years ago, such progress was unthinkable. We’ve completely upended the therapeutic paradigm with the institution of immunotherapy. Unfortunately, the majority of patients still do not benefit long term, but we are now seeing long-term survival in many who would have succumbed to their metastatic lung cancer within the first year or two. We are manipulating the immune system to obtain maximum advantage and basically redeploying the body’s natural defenses against cancer.

Dr. Langer, what are your areas of scientific focus?

Langer: In recent years, I have been involved in studies evaluating the role of checkpoint inhibitors in combination with standard chemotherapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). A randomized phase II trial that I led resulted in early conditional FDA approval for pembrolizumab combined with chemotherapy in patients with treatment-naïve, nonsquamous NSCLC; the benefits were later confirmed in a much larger, global phase III trial, converting conditional into full approval.

Prior to that, in the early 90s, I spearheaded one of the first studies to evaluate the combination of carboplatin and paclitaxel in advanced NSCLC; this regimen remains one of the standard therapeutic regimens we still use today to treat lung cancer. That study, at the time, showed one of the best response rates and survival we had seen to date. The other aspect of my career about which I’m most proud is what we call combined modality. In locally advanced lung cancer, we have seen an evolution from radiation therapy alone to chemoradiation and now chemoradiation followed by immunotherapy. In the ‘90s and early “aughts,” I had the privilege of being the co-principal investigator on a study comparing sequential to concurrent chemoradiation, which showed a survival advantage for concurrent chemoradiation, as we had posited based on prior work we had done. I’ve been involved in combined modality work ever since. It’s really part of my lifelong professional devotion to the integration of different modalities and different cancer disciplines.

Dr. Langer, what does this award mean to you and why did you select Dr. Marmarelis as the recipient of the Early Career Investigator Award?

Langer: It’s a major honor; I think it puts a spotlight on thoracic oncology in particular. Sadly, lung cancer remains the number one cancer killer in the United States. It’s important that the world at large be aware of some of the major advances we’ve made in the last five to seven years in immunotherapy and targeted therapy.

I’m particularly gratified that the award comes in two parts, that I get to help fund a junior researcher with whom I am privileged to work. Melina Marmarelis is one of our up-and-coming clinical researchers. She’s incredibly intelligent, incredibly nice, incredibly goal-directed, and very efficient. She’s heavily invested in conducting clinical trials and she’s just a few years out from finishing her fellowship. With my encouragement, she parachuted into our Mesothelioma Program, and she’s now the lead. I provide some advice, but, at this point, I think it’s more appropriate that I play a role in the background. I want her to really run the show; she, in combination with Keith Cengel of radiation oncology, heads the Mesothelioma Center, which is gaining increasing national prominence.

Dr. Marmarelis, what does it mean to be a physician-scientist?

Marmarelis: Physician-scientists look at some of the questions that are raised while caring for patients and investigate them in various ways. I am a clinical researcher, so for me, my lab is really the clinic, and the questions that come up when I see patients are the ones that we investigate either by looking back at similar patients or by investigating in larger databases or creating clinical trials. We get ideas from what we see in clinic, and we get ideas from what we are observing in our database research, and we definitely have a dialogue between the clinic and the larger-scale research that we do.

Dr. Marmarelis, has there been any recent progress in the treatment of mesothelioma?

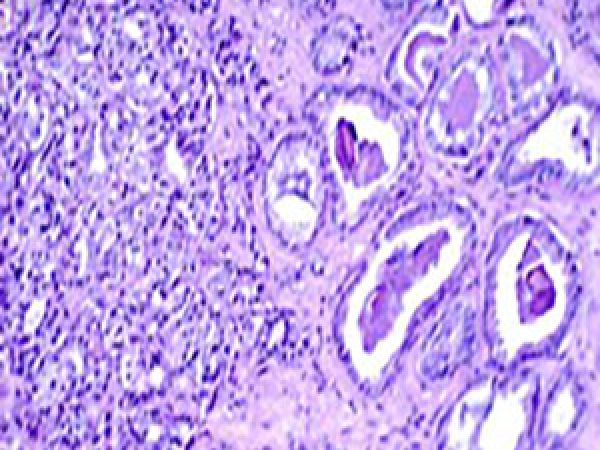

Marmarelis: Mesothelioma is a rare disease that affects about 2,000 to 3,000 people a year in the United States. It is directly linked to exposure to asbestos. It is primarily seen in the pleura, but it can also be seen in the peritoneum. The biggest development in mesothelioma therapy recently was a randomized clinical trial looking at the combination of the immunotherapy drugs ipilimumab and nivolumab versus chemotherapy in untreated patients with pleural malignant mesothelioma. What this study showed was that overall, the combination immunotherapy gave better outcomes to the whole population, but looking closely, what researchers saw was that the patients with a specific type of mesothelioma, called non-epithelial, were the ones that were driving that result because they generally don’t do as well on chemotherapy. So really what came out of that trial were two things: One is that immunotherapy can be very effective in mesothelioma, and the second is that we now need to have a histology-based approach to therapy, which is new. So now we’re looking at the different types of mesothelioma and making treatment decisions about what systemic therapies each of those subsets of patients would benefit from.

Dr. Marmarelis, please talk about your clinical and research focus and the studies you are currently conducting.

Marmarelis: I see patients with lung cancer and with mesothelioma, and my research focuses on early-phase clinical trials in these diseases. I also do larger database analyses that are used to inform clinical trial design. I’ve primarily focused on targeted therapies and post-immunotherapy disease progression. An important aspect is ensuring that we find patients that have molecular alterations that can benefit from targeted therapy. So, I also have several clinical trials along with other investigators looking at improving the rates of molecular testing in newly diagnosed lung cancer patients. In mesothelioma, I’m involved mostly in therapeutic clinical trials, looking at the incorporation of immunotherapy but also novel therapeutic agents.

Dr. Marmarelis, what does the award mean to you, and how will the funding help advance your research?

Marmarelis: I’m very excited about this award. To be able to have additional research funding helps in a number of ways. We have several projects ongoing that need additional support. In particular, I run a large database of patients with EGFR, ALK, and ROS1 alterations collected across 12 sites in North America. Maintaining and cleaning up that database requires a lot of expertise and work. So being able to fund those positions and this important work really helps both to advance the field but also to inform future clinical trials and trial design.

What do you see at the horizon for lung cancer therapy? What are the next developments in immunotherapy?

Langer: I think one of the new and exciting therapeutic strategies are antibody drug conjugates (ADCs), where monoclonal antibodies that target a specific antigen on cancer cells can become the delivery system of a toxic payload. It’s a therapeutic “smart bomb,” a targeted missile that, at least in theory, goes straight to the cancer. For example, with trastuzumab deruxtecan, a prototypical ADC, we are now seeing better response rates than we had observed previously with chemotherapy in lung cancer patients with HER2 mutation. The median progression-free and overall survival seem to be better than what we could have achieved historically, so it is a breakthrough. That’s only one of the next waves of therapeutic research. The other very important wave includes new combinatorial strategies with standard checkpoint inhibitors (CPIs). We have at least five CPIs now approved in thoracic oncology, and I think the strategy, at least for the next five to 10 years, will be to figure out how best to deploy those immunotherapy drugs and how best to combine them with other approaches to manipulate or kickstart the immune system. There’s a lot of hope that various monoclonal antibody combinations, adding vaccines and other immunotherapeutic strategies, will make a major difference in clinical outcomes. Exporting these advances to patients with early-stage disease who have undergone curative resection and to those undergoing definitive chemo-radiation for locally advanced NSCLC holds the promise for the next incremental benefit in thoracic oncology.

Marmarelis: I think we’re identifying that lung cancer is not just one disease, but many diseases that are characterized both by their molecular subtypes and the amount of immune regulation within the tumor microenvironment. I think we’re getting better at tailoring treatment to molecular subtypes, but we’re not quite able to tailor treatment to the level of activity of the immune system surrounding the tumor. I think the next phase will be to use those two characterizations in order to deliver more personalized care to patients with lung cancer.