SABCS 2022: The Uncharted Territory of HER2-low Breast Cancer

Imagine a series of switches on a wall.

When a patient is diagnosed with cancer, physicians often decide which treatment to give based on the tumor’s unique profile of which switches are “on” and which switches are “off.” Breast cancer is possibly the best-known example of this decision-making; as one of the first tumor types to be subclassified based on the presence or absence of molecular markers, the positions of these switches have guided treatment for decades.

If a patient’s tumor expresses hormone receptors, such as the estrogen and/or progesterone receptor, they may be eligible for endocrine therapy—treatments that block the activity of the estrogen receptor or the production of estrogen in the body. If a patient’s tumor has overexpression of the growth factor receptor HER2, they may be eligible for drugs that prevent HER2 activation. If neither the hormone receptor switch nor the HER2 switch is “on,” patients often receive chemotherapy.

But what if HER2 isn’t a switch—what if it’s a dimmer?

While researchers know that HER2 expression varies on a continuous scale from very low to very high, treatments targeting HER2 have historically only worked in patients with the highest levels of expression; everyone else has been ineligible whether their tumors have low levels of HER2 or none at all. This paradigm shifted in August 2022, when trastuzumab deruxtecan (Enhertu, T-DXd) became the first therapy approved to treat breast tumors with HER2 expression greater than zero but less than the threshold of eligibility for other drugs.

The new approval has left researchers with several questions: Do HER2-low tumors represent a new subtype of breast cancer? How should physicians measure HER2 in these tumors to determine who will benefit most from T-DXd?

At the 2022 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (SABCS), held in a hybrid format December 6-10, researchers discussed the nuances underlying these questions. In the special session “HER2-low: A Separate Entity?” experts debated whether HER2-low should be considered a biomarker, a separate subtype, or something else entirely. Along with UT Health San Antonio, the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) is a co-sponsor of SABCS and is proud of this ongoing collaboration to benefit patients with breast cancer.

HER2 Detection and Treatment

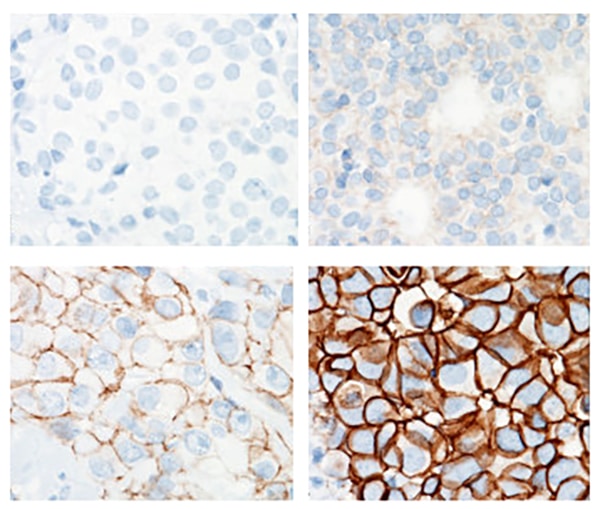

HER2 status is routinely assessed in breast cancer using immunohistochemistry (IHC), which stains HER2 molecules in human tissue. Pathologists then score the sample according to staining strength—IHC-0 if the tissue has no visible HER2 expression, and 1+, 2+, or 3+ as HER2 expression increases.

In the past, most patients were eligible for HER2-targeted therapy only if their tumors had a HER2 staining score of IHC-2+ with confirmed genetic amplification or IHC-3+. Such patients historically received monoclonal antibodies targeting HER2, such as trastuzumab (Herceptin) and pertuzumab (Perjeta).

Unfortunately, some tumors do not respond to these therapies, or they develop resistance, necessitating new treatment options. A new class of drugs called antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs)—two-part molecules consisting of an antibody linked to a toxin—offered some hope. The antibody portion of these molecules recognizes a protein on the surface of cancer cells—in this case, HER2. When the ADC binds to HER2, it is internalized into the cell, where it releases its toxic payload.

Two HER2-targeting ADCs—T-DXd and trastuzumab emtansine (Kadcyla, T-DM1) have been approved to treat tumors with high expression of HER2. However, because even low HER2 expression is sufficient to attract ADCs to the cancer cells, researchers wondered whether T-DXd might effectively treat tumors without HER2 overexpression.

Additionally, studies have shown that once a cancer cell dies following exposure to T-DXd, it releases its toxic payload into the tumor microenvironment, where it can kill cancer cells that do not express HER2—a phenomenon known as the bystander effect.

In the DESTINY-Breast04 clinical trial, patients with HER2-low disease randomly assigned to receive T-DXd had a significantly longer median overall survival and median progression-free survival than patients treated with a physician’s choice of treatment—often endocrine therapy for patients with hormone receptor-positive disease and chemotherapy for patients with hormone receptor-negative disease. These results led to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of T-DXd for the treatment of patients with HER2-low breast cancer.

An Independent Subtype?

With a unique treatment option available, researchers began looking more closely at the molecular and clinical characteristics of tumors with IHC-1+ and IHC-2+ staining. Do those characteristics distinguish HER2-low breast cancer enough from other subtypes to consider it a separate entity?

Giuseppe Curigliano, MD, PhD, an associate professor of medical oncology at the University of Milano and the head of the division of Early Drug Development at the European Institute of Oncology in Italy, argued in favor of a reclassification.

Curigliano explained that HER2-low breast cancer needs to fulfill three criteria to constitute an independent entity: a prognosis distinct from other subtypes, a unique treatment plan, and defining biological characteristics with accurate assays to identify them.

In terms of a distinct prognosis, researchers have noticed that HER2-low tumors are less frequently grade 3 and commonly have a lower proliferation index than triple-negative tumors. Other studies have suggested that patients with HER2-low breast cancer have a longer disease-free survival and lower risk of recurrence than patients with HER2-negative or HER2-high tumors.

As for a unique treatment plan, Curigliano summarized this point in a single sentence: “We have a drug approved for the treatment of the disease.”

Curigliano elaborated by explaining that T-DXd may serve patients with HER2-low tumors better than treatments they would have otherwise received. In a retrospective study presented as a poster during the meeting, in which the outcomes of patients with hormone receptor (HR)-positive breast cancer were evaluated by HER2 status, those with HR-positive, HER2-low tumors experienced fewer pathological complete responses, a shorter median overall survival, and a shorter median progression-free survival than those with HR-positive, HER2-negative tumors when treated with endocrine therapy plus a CDK4/6 inhibitor.

These findings complement the DESTINY-Breast04 trial, which positioned T-DXd as superior to endocrine therapy and chemotherapy for patients with HER2-low disease.

In addition to HER2 expression, a new subtype of breast cancer would require a distinct set of biological characteristics. Curigliano offered several examples of genetic and transcriptomic differences between HER2-low and HER2-negative tumors, including differences in driver mutation prevalence (namely TP53 and PIK3CA), signaling pathway activation (such as androgen receptor signaling and fatty acid metabolism), and overall gene expression profiles.

Curigliano argued that more robust assays to differentiate HER2-low from HER2-negative disease are also crucial. In a study presented at SABCS 2021, 30 percent of patients with IHC-0 breast tumors responded to T-DXd. To assess whether these responses may be driven by tumors with “ultralow” HER2-expression—expression that is undetectable by IHC but potentially detected by sequencing or mass spectrometry—researchers are including patients with HER2-ultralow tumors in the ongoing DESTINY-Breast06 trial.

“We have an obligation for our patients to make these valuable, clinically annotated specimens available for secondary studies with assays that are analytically and clinically validated and that could help us better define which patients are most likely to benefit from these exciting new therapies,” Curigliano said.

A Biomarker of T-DXd Efficacy?

Sara Tolaney, MD, MPH, chief of the Division of Breast Oncology and associate director of the Susan F. Smith Center for Women’s Cancers at Dana-Farber Cancer Center and an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, argued that HER2-low breast cancer falls short of a new subtype.

MD, MPH

Tolaney largely agreed with the subtype criteria outlined by Curigliano, but with one caveat: Distinct cancer subtypes must have distinct molecular drivers. Tolaney stressed that HER2-low tumors are not driven by HER2, as evidenced by the fact that other HER2-targeted therapies do not improve the survival of patients with HER2-low disease. The efficacy of T-DXd is therefore more likely dependent upon the cytotoxic payload than the blockade of HER2 activity.

“This suggests that HER2-low is not a new subtype characterized by an oncogenic driver but is rather a biomarker for the benefit of antibody-drug conjugates that potently target HER2,” Tolaney said.

According to Tolaney, the distinct prognosis and many of the unique biomarkers of HER2-low breast cancer also likely result from other oncogenic drivers, namely the estrogen receptor (ER); as ER expression increases, the likelihood of HER2-low tumors also increases, suggesting a link between the two factors. Further, when researchers adjust for HR status, differences in survival rates between patients with HER2-low and HER2-negative tumors often disappear.

The prevalence of HR-positivity may also explain some biological features of HER2-low disease, such as earlier stage at diagnosis and lower proliferation index, both of which are also common among ER-positive tumors. In one study of breast cancer transcriptomes, Tolaney further showed that samples clustered primarily based on HR expression, and that HER2-low and HER2-negative samples with the same HR status were virtually indistinguishable.

Tolaney also argued that HER2 expression itself is not consistent enough to define an independent entity of breast cancer. Using data from multiple studies, she demonstrated that HER2 expression can vary widely among different areas of a tumor, different metastatic sites, and/or different time points during a patient’s treatment.

“In real life, we need to think about the patient who sits before us, who has multiple different tissue biopsies with different results,” Tolaney said. “Which one do we use to make a decision about selection for trastuzumab deruxtecan?”

Practical Considerations

Whether HER2-low breast cancer represents an independent subtype or not, the survival benefit imparted by T-DXd makes accurate HER2 detection and analysis an urgent priority. The session organizers brought in David Rimm, MD, PhD, director of the Yale Cancer Center Tissue Microarray Facility and Yale Pathology Tissue Services, and a professor of pathology and medicine at Yale School of Medicine, to provide some context around how researchers are working toward better assays.

Rimm explained that the current tests are designed to identify samples with the highest levels of HER2 expression. The staining intensity is calibrated such that the difference between IHC–3+ and IHC-2+ is clear, but that can cause ambiguity in the IHC-0 to IHC-1+ range.

Pathologists also are not as adept at differentiating IHC-0 from IHC-1. In one study, a group of 18 pathologists agreed on whether a set of 170 samples was IHC-3+ or not IHC-3+ 89 percent of the time, but they only agreed on whether the same samples were IHC-0 or not IHC-0 59 percent of the time. Rimm stressed that pathologists must adjust to the importance of differentiating zero from nonzero scores.

Rimm suggested that another solution may involve redesigning the assay to make it more quantitative—measuring the precise concentration of HER2 protein—and more sensitive to differences among lower HER2 expression levels. In such an assay, researchers could use HER2-expressing cell lines (in which the concentration of HER2 protein is easily determined) to create a standard curve that computationally correlates IHC staining intensity with an empirical HER2 concentration.

This, Rimm said, would allow researchers to understand exactly what range of HER2 expression indicates a likely response to T-DXd. “I would argue that most oncologists would not accept an ordinal value for sodium or magnesium or potassium or glucose,” Rimm said. “Neither should you accept an ordinal value for HER2.”

The session also featured Patricia Spears, a patient advocate and research manager of the Patient Advocates for Research Council at the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, who informed the discussion from a patient perspective. Spears agreed with Rimm that precision is crucial when determining eligibility for T-DXd, because getting it wrong could have significant consequences.

On one hand, Spears explained, T-DXd offers a new treatment for some patients previously classified as triple-negative, for whom therapeutic options are limited. Becoming eligible for T-DXd could change the course of these patients’ treatment; however, ADCs also pose side effects that warrant caution in terms of overprescribing. Spears warned against giving T-DXd to patients unlikely to benefit from it, especially to patients with nonaggressive or early-stage disease.

“It’s really important to get this right,” Spears said. “We rely on the pathologists for our treatments 110 percent, and we trust that their information is accurate. Whatever test comes out for this, I really want it to be equitable and accessible to everyone.”