AACR Annual Meeting 2024 Highlights: 6 Days of Groundbreaking Science

How does one recap six days of impactful basic, translational, and clinical research in an hour-and-a-half closing plenary session? One does not. Three, perhaps. Scientific Program chairs Keith T. Flaherty, MD, FAACR, of Mass General Cancer Center, and Christina Curtis, PhD, of Stanford University, invited three distinguished speakers to review the groundbreaking science presented at the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Annual Meeting 2024, held April 5-10.

This year, the program planning committee selected the theme of inspiring science, fueling progress, and revolutionizing care. The final plenary session proudly showcased how a variety of researchers—from basic scientists to epidemiologists to clinical investigators—rose to the challenge presented by this theme to share their contributions to the field of cancer research.

Basic and Translational Research

In a special session titled, “Strategies to Effectively Communicate Science to the Public,” William G. Nelson, MD, PhD, Editor-in-Chief of Cancer Today (AACR’s magazine for cancer patients and their families), advised attendees to organize sprawling scientific stories by boiling them down to three main points. Mikala Egeblad, PhD, of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, took this advice to heart when tasked with summarizing the basic and translational science presented at the meeting.

Egeblad’s first take-home message was to embrace the complexity of cancer and recognize it as a disease that affects—and is affected by—the entire body. Two plenary sessions discussed this concept in detail. One about the tumor microenvironment described new experimental and computational approaches to study how a tumor interacts with its immediate surroundings. It also featured a presentation about how the bacteria that reside inside a tumor can shape the gene expression programs and behavior of cancer cells.

In another plenary, centered around metastasis, researchers described the complexity of metastatic cells, including how signaling from a tumor can reshape the sites of future metastasis. In some cases, such signaling can cause damage to other organ systems, resulting in problems such as fatty liver disease or thrombosis.

Egeblad also mentioned several presentations on how neurons in and around the tumor can stimulate cancer growth, and how the tumor can, in turn, signal back to the neurons to boost their tumor-promoting behaviors. She further highlighted studies of how aging-related clonal hematopoiesis may help activate inflammation and awaken dormant tumor cells, and how aging can reprogram stromal and immune cells.

For her second take-home message, Egeblad emphasized that basic cancer research is expanding our repertoire of drugs and drug targets. In the Opening Plenary, Benjamin Cravatt, PhD, of Scripps Research Institute, discussed a technique called activity-based protein profiling that can find novel binding pockets in previously undruggable proteins, and Nobel Laureate Carolyn Bertozzi, PhD, FAACR, of Stanford University, described how her lab is targeting sugar tags that accumulate on cancer cells.

Egeblad also touched on new models informing basic and translational research, including novel mouse models and drug screening platforms for patient-derived organoids. However, the ever-expanding ability to perform high-throughput transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic analyses on patient tissue may have revolutionized our relationship with model systems. “What we really learned is that the patient is now the model,” Egeblad said.

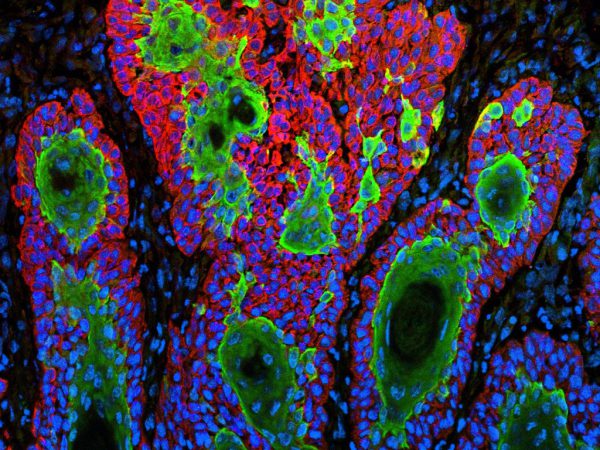

The amount of available data requires new ways of looking at complex information to develop a multidimensional understanding of cancer, Egeblad explained in her third take-home message. Many presentations—including a plenary talk by Peter Sorger, PhD, of Harvard Medical School—demonstrated the power of spatial multiomics approaches, not only in 2D samples but in 3D as well.

Artificial intelligence (AI) can help us make sense of these multidimensional analyses, Egeblad argued. This year featured the AACR Annual Meeting’s first plenary session focused on AI, in which researchers presented new uses for AI in drug development and precision medicine. Two speakers in the Opening Plenary also discussed how AI can identify patterns in massive data sets that humans cannot see, potentially leading to new drug targets or better patient stratification.

“AI is here,” Egeblad said. “There’s so much data, so much information we can gain, but we need computational biology and AI to go through it all.”

Prevention, Early Detection, Population Sciences, and Disparities

Melissa A. Simon, MD, MPH, of the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, echoed the importance of AI in all facets of cancer research; however, she also emphasized the potential pitfalls that may arise from a lack of diversity in training sets, or implicit bias reflected in the programming.

“If we, across the entire translational cancer research spectrum, acknowledge those limitations of AI and the current data available when we [develop] these models and integrate them into our work, then we can move forward in science more equitably,” Simon said.

She added that the use of molecular and genetic profiling to direct treatments and predict outcomes could face the same challenges. In a session in honor of Edith Mitchell, MD, a panel of experts discussed racial and ethnic disparities in biomarker testing, as well as differences in molecular characteristics of tumors from patients of different races.

While newer computational methods can help researchers make sense of such differences, they can only process data that exists, Simon said. She stressed the importance of collecting data on environmental exposures and other social determinants of health to better understand their impacts on cancer biology and health disparities. She also reminded attendees that, when conducting disparities research, one should not conflate race and ethnicity with genetic ancestry; while both can provide important insights, race and ethnicity are social variables, not biological variables, and should be treated as such.

Simon also emphasized the importance of understanding how environmental factors interact with individuals’ unique genetic makeup. The earliest steps of carcinogenesis are influenced by a combination of genetic factors and environmental exposures, she said; additional information about how the two combine can paint a better portrait of each individual’s cancer risk—with implications for personalized prevention and cancer interception strategies.

Other considerations for cancer prevention included the mitigation of environmental risk factors, with a popular session on how new anti-obesity drugs may impact cancer risk. Simon touched on population-based screening approaches—including multicancer early detection tests—to find cancers when they’re easier to treat. However, she cautioned that researchers must carefully weigh the potential harms of overdiagnosis and financial burden when deciding how to implement such tests.

“An important issue in cancer screening still remains how to optimize the trade-off between benefits and harms for both individuals and society,” Simon said. “It’s not just about translating new biological or technological knowledge into new tests but also about knowing who’s at risk, and who should use such tests, when, and how.”

Clinical Research and Trials

Clinical trials committee co-chair Ryan B. Corcoran, MD, PhD, of Mass General Hospital Cancer Center, felt honored to close out the entire meeting with a wrap-up of what he called “an exceptional clinical trial program.”He began by highlighting a handful of new targeted therapies.

KRAS inhibitors, including those that target mutations beyond G12C, have attracted a great deal of attention since the approvals of sotorasib (Lumakras) and adagrasib (Krazati) in 2021 and 2022, respectively. The multi-RAS inhibitor RMC-6236—which, unlike sotorasib or adagrasib, inhibits the active conformation of all three RAS isoforms—showed promising safety and efficacy in patients with lung and colorectal tumors harboring various KRASG12 mutations. Additionally, responses were observed in patients with NRAS mutations, which Corcoran noted were among the first clinical evidence of successful NRAS targeting.

“I think this is an important proof of concept for the field that we can move beyond G12C into other mutations and other RAS isoforms,” Corcoran said.

Novel antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) also had significant representation at the meeting. Corcoran highlighted a phase II trial of sacituzumab tirumotecan, consisting of a topoisomerase I inhibitor linked to a TROP2-targeting antibody. In patients with previously treated gastric cancer, the disease control rate was 80.5% with a median response duration of 7.5 months.

Another presentation featured a novel poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor that showed promising efficacy in patients with homologous recombination repair-deficient breast cancer in the phase I/II PETRA trial. The inhibitor, saruparib, selectively inhibits PARP1, whereas all currently approved PARP inhibitors target both PARP1 and PARP2, leading to higher toxicity.

Corcoran also highlighted a study evaluating a new combination regimen for the existing PARP inhibitor olaparib (Lynparza). In the phase II/III PARTNER trial, researchers found that combining olaparib with platinum chemotherapy, a regimen that previously proved too toxic to use at therapeutically beneficial doses, could benefit patients if olaparib was given on a “gap” schedule—48 hours after the start of chemotherapy. In a cohort of patients with BRCA-mutated breast cancer, olaparib plus carboplatin and paclitaxel improved event-free and overall survival compared to chemotherapy alone. However, the combination did not improve outcomes in a cohort of patients with triple-negative breast cancer whose tumors did not harbor BRCA mutations.

Another novel combination therapy was tested in the phase I/II KRYSTAL-1 trial of adagrasib plus the EGFR inhibitor cetuximab (Erbitux) in KRASG12C-mutated colorectal cancer. The regimen, designed to prevent EGFR-mediated resistance to adagrasib, had a disease control rate of 85.1%, a median progression-free survival of 6.9 months, and a median overall survival of 15.9 months, in heavily pretreated patients. This study was published simultaneously in the AACR journal Cancer Discovery.

New strategies for immunotherapy were also quite popular, Corcoran noted. In another attempt to improve the efficacy of PARP inhibitors, researchers combined olaparib with the immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab (Keytruda) as maintenance therapy in patients with metastatic squamous non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), but the combination did not improve progression-free or overall survival compared with pembrolizumab alone. In contrast, a phase I/II trial combining the checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab (Opdivo) with the PI3K inhibitor copanlisib showed encouraging responses in patients with metastatic microsatellite-stable colorectal cancer, a population that does not often respond to checkpoint inhibition.

In a promising advance for allogeneic CAR T cells, researchers tested CTX130, a CD70-targeting CAR T-cell therapy, in patients with advanced, treatment refractory clear cell renal cell carcinoma. The clinical benefit rate among patients in this phase I trial was 81.3%, including a complete response lasting longer than three years, among the longest ever observed in treatment-refractory solid tumors, Corcoran noted. The developers of CTX130 are now testing an improved version of the therapy, CTX131, in a phase III trial. This study was published simultaneously in the AACR journal Cancer Discovery.

Finally, Corcoran discussed data from a clinical trials minisymposium on cancer vaccines, including updated results from a phase I clinical trial of a personalized neoantigen vaccine, autogene cevumeran, for patients with pancreatic cancer. Researchers showed that the vaccine produced robust expansion of neoantigen-targeted T-cell clones that remained present and responsive for up to three years. Further, patients who experienced T-cell responses had a significantly longer median recurrence-free survival than patients who did not.

All in all, Corcoran was impressed by the data presented at the meeting, clinical or otherwise. “This is actually an incredibly exciting time in clinical oncology,” he said. “We are really seeing [researchers] harnessing and leveraging the phenomenal scientific advances in the last year and translating them into approaches that are truly impacting the lives of cancer patients.”