Harnessing the Immune System to Treat Pancreatic Cancer

Editor’s note: June is Cancer Immunotherapy Month. You can find more information and resources on this topic here.

Cancer immunotherapy, a type of treatment that works by harnessing the power of the immune system to destroy tumor cells, has become one of the hottest topics in cancer research in recent years. It seems as though you can’t turn the page of any scientific journal without coming across at least one study describing new immunotherapeutic approaches to treat cancer. Cancer immunotherapy is also frequently discussed on our blog, as many AACR scientists are working diligently to better understand these treatments and take them from bench to bedside.

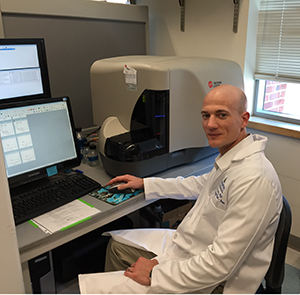

Dr. Eric Lutz, 2013 recipient of the Pancreatic Cancer Action Network-AACR Career Development Award, in his lab.

One of these scientists is Eric R. Lutz, PhD, an assistant professor of oncology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Lutz gained an interest in the immune system early in his career, starting in his first research position. “My interest in tumor immunology sprung from a research technician position I accepted after graduating from college. At the time, I had a wide range of scientific interests, and was looking for something to capture me,” recalls Lutz.

It was then that he met Elizabeth Jaffee, MD, professor of oncology, and Todd Reilly, PhD, then a new assistant professor in oncology, who interviewed him for a research position in their group at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center. “They told me they were studying the development of immunotherapies for breast and pancreatic cancer, and that they were already testing their approach in patients; I was blown away,” he says. Lutz excelled in this position, and ultimately went on to get his doctorate in Immunology and Molecular Biology from Johns Hopkins, all the while maintaining his enthusiasm for tumor immunology.

During his postdoctoral fellowship, also under the direction of Jaffee at Johns Hopkins, Lutz was awarded the AACR-FNAB Fellows Grant for Translational Pancreatic Cancer Research to investigate cancer immunotherapy in the form of a vaccine against pancreatic cancer. “At that time,” Lutz recalls, “cancer immunotherapy was not a popular idea, but that made it even more interesting to me. I’ve been hooked on it ever since.”

But what is it that makes this type of therapy so unique and important? This seems an easy question for Lutz to answer: “Its [cancer immunotherapy’s] potential to provide long-term protection through the development of immune memory; its potential to eradicate large tumor burdens; and its potential to provide protection with less toxicity.”

Additionally, immunotherapy may provide an alternative treatment approach when other therapies fail. “It is important to remember that the mechanisms immunotherapy uses to kill tumor cells are very different from classical approaches, such as chemo- and radiation therapy,” he says. “Unlike these more classical approaches that generally act directly on the tumor cells or their supporting stromal cells, the antitumor effects of immunotherapy are indirect and mediated through the activation of immune cells.”

This aspect of immunotherapy could prove especially beneficial to patients suffering from pancreatic cancer, which has remained a focus of Lutz’s laboratory now that he is an assistant professor. “Pancreatic cancer has been difficult to treat, in part because early detection methods are lacking and most patients have advanced, unresectable disease at the time of diagnosis, but also because common chemotherapeutic agents and radiation have had limited efficacy,” says Lutz. “Since immunotherapy acts through different mechanisms, the drug and radio-resistance of pancreatic cancer does not mean that it will not respond to immunotherapy. In fact, we have shown that patients who fail to respond to treatment with up to three different prior therapies can respond to subsequent treatment with immunotherapy, and we have also observed regression in metastatic lesions following treatment with immunotherapy.” However, while Lutz is enthusiastic about the potential for immunotherapy as a treatment for pancreatic cancer, he does urge that more research is needed, acknowledging that “we still have a long way to go.”

And his group is continuing to uncover these mysteries. In 2013, Lutz was awarded another grant through AACR, the Pancreatic Cancer Action Network-AACR Career Development Award. The goal of this project is to exploit the cancer “mutome” (a group of gene mutations common to pancreatic cancer) for personalized cancer immunotherapy, something he considers to be the future of immunotherapy. “The latest studies are showing that combinations of immunotherapies, or combinations of immunotherapies with other more classical therapies such as chemotherapy and radiation therapy, can be more effective than single agents alone,” he says. “The trick will be determining how to best combine the different therapies that are being developed, and determining how to match the appropriate treatment combination for each patient. I think there is real potential for this and other personalized approaches that are under development.”

When asked about his views on the future of cancer immunotherapy, and the obstacles that it faces, Lutz commented on its limited use. “With a few exceptions, immunotherapy is still predominantly offered only to patients enrolled onto research studies at larger medical centers.” A critical step, he feels, is to move these newer approaches through clinical development and approval so that they become readily available to patients. But he also recommends improved education about such new treatment approaches for doctors and nurses at local community medical centers and hospitals. “We need to train them how and when to use approaches that are approved,” he says. “We also need to increase public awareness to make sure that patients know that options like immunotherapy exist, even if they don’t find out through their local hospital.” Additionally, Lutz supports increasing the number of cancer immunotherapy clinical and research training programs, as well as growing the biomedical workforce – including researchers, physicians, and nurses – to study and administer this therapy.

“There’s no doubt that it’s a very exciting time to study cancer immunotherapy,” says Lutz. “It’s great to see where things have gone over the past 15 years, and to see that many more of us now realize the potential for this type of treatment.”