Educating Himself and Fellow African Americans About Cancer and Clinical Trials

After his 2011 PROSTATE CANCER diagnosis, U.S. Army Col. (ret.) Gary Steele learned about cancer health disparities and the importance of participating in cancer clinical trials.

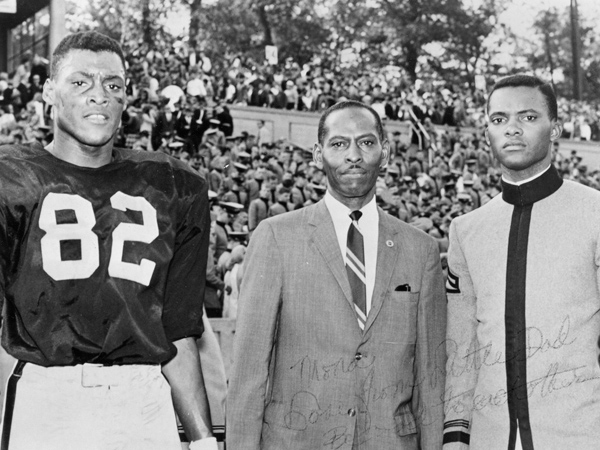

U.S. Army Col. (ret.) Gary Steele has deeply instilled values of service ingrained by his parents and molded through his years as a cadet at the U.S. Military Academy. Col. Steele made history at West Point as the first African American varsity football player and went on to serve in the Army for 23 years.

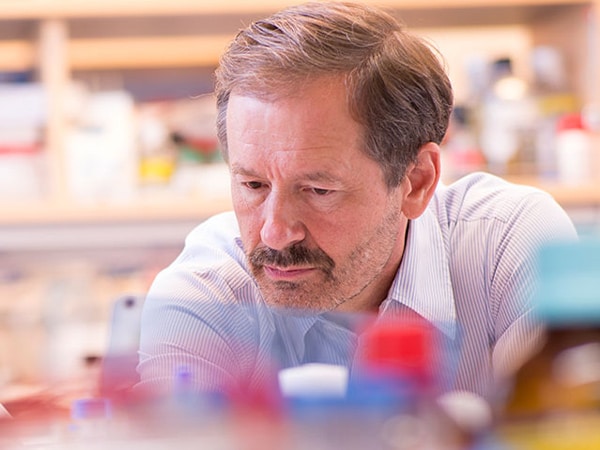

Diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2011, Col. Steele has a new mission to educate others on cancer health disparities and what he has learned from his own cancer journey and experience with cancer clinical trials.

“When I think about cancer and I think about the large numbers of African Americans impacted by so many types of cancers, I think about the need for education,” said Col. Steele.

Col. Steele’s survivor story was featured in the AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2020, one of the latest initiatives from the AACR to support and advance cancer health disparities research. The report provides a comprehensive overview of the science of cancer disparities and issues a broad call to action to advance health equity.

After a series of treatments that failed to halt his prostate cancer, Col. Steele and his wife, Mona, traveled to the Johns Hopkins Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center for a second opinion. His Hopkins team suggested a clinical trial.

“I had them explain to me what a clinical trial was because I didn’t know. I was not educated at all on this stuff,” recalled Col. Steele. After talking through their options, Col. Steele says he and his wife decided to participate in the trial.

“We have two sons and I thought that if I end up being okay with this clinical trial, then I could be helping my sons,” he said.

While his initial focus was on himself and his family, Col. Steele’s views evolved to include the potential benefits to others, especially other African American men with prostate cancer.

“Maybe something that I say or something that I do through the clinical trial path will help somebody make a decision that’s going to help themselves and help this huge thing we know as cancer—which is much bigger than the individual,” he said.

The ability to think beyond oneself and serve the larger group is something that was instilled in him by his parents.

Col. Steele’s father, Frank Steele, enlisted in the U.S. Army in the 1940s and his first duty station was at West Point, where he served as a Buffalo Soldier. Before the military was desegregated, Buffalo Soldiers were regiments of Black military personnel who first earned their nickname from the Indians for their warrior valor.

Decades later, Col. Steele and his brother attended West Point as cadets. Col. Steele gained a great appreciation for the value of teamwork on the football field.

“I was just one person. I was the only black guy on the team, but we were a team,” he said. “It takes more than one to win.”

Col. Steele and his Army teammates put up impressive numbers and scored some big wins during his three years as a varsity player, which helped earn Col. Steele a place in the Army Sports Hall of Fame in 2013.

Col. Steele says he has been clean and clear of prostate cancer since late 2015. He credits his ongoing participation in the clinical trial for his success.

“It worked for me. I can only say educate yourself, take care of yourself. Think of your family and think about paying it forward.”

The appreciation for paying it forward came full circle for Col. Steele in 2017, when he was diagnosed with his second cancer that disproportionately impacts African Americans—multiple myeloma.

His second diagnosis hit close to home and again highlighted the broader value of participating in cancer clinical trials when Connie, a long-time family friend and the wife of one of Col. Steele’s West Point buddies, was diagnosed with multiple myeloma, a blood cancer that is expected to be diagnosed in nearly 35,000 people in the U.S. in 2021.

Connie, who ultimately died of her cancer, participated in a clinical trial for the therapeutic that is now standard of care for multiple myeloma. Today, Col. Steele’s myeloma, and that of many other patients with the disease, is being managed by that therapeutic.

“I look at what she did to pay it forward for me,” said Col. Steele. “At the end of the day, you know, there is that one saying that is on your tombstone. There is the date you were born. And there is the date you die. But there is also a dash in between. So, the question is really about what you do with that dash.”

Return to AACR Stories Home