Q&A With Raymond DuBois, MD, PhD, on Colorectal Cancer Prevention and Treatment

Basic scientific discoveries, like the unraveling of the mechanisms of DNA repair, for which Paul Modrich, PhD, of Duke University, Thomas Lindahl, PhD, of the Francis Crick Institute and Clare Hall Laboratory in the UK, and Aziz Sancar, PhD, of University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, shared the 2015 Noble Prize in Chemistry, have been central to developing the current approaches to cancer prevention and treatment. Deficiencies in DNA mismatch repair, a process by which some types of DNA damage is repaired—the underlying mechanisms of which Modrich deciphered—causes one of the most common forms of hereditary colon cancer.

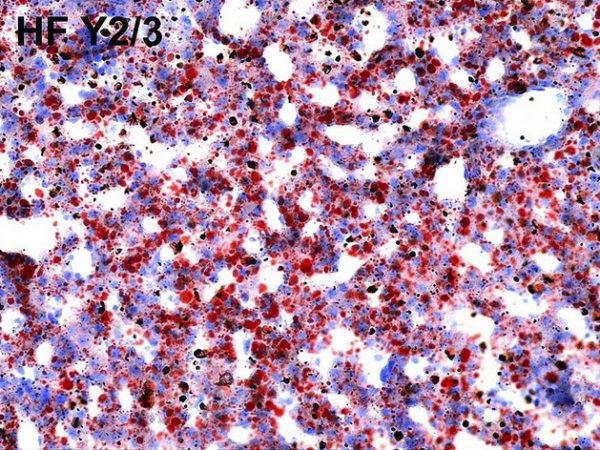

Micrograph showing tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in a case of colorectal cancer with evidence of microsatillite instability-high on immunostaining.

Colorectal cancer screening has been particularly effective at reducing colorectal cancer incidence and death rates. However, a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published in August shows that despite the successes achieved with colorectal cancer screening, we remain far short of achieving the Healthy People 2020 target of having 70.5 percent of U.S. men and women ages 50-75 up to date with screening by 2020. A recent study published in the AACR journal Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, also identified large pockets of the country where colorectal cancer death rates are not declining as much as they do in the rest of the nation.

We asked Raymond DuBois, MD, PhD, executive director of The Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University, and president and chairman of the AACR Foundation, to share with us his thoughts on just how far we have come with preventing and treating colorectal cancers, and what more needs to be done.

What are the current colorectal cancer screening guidelines and what are the challenges with getting people to adhere to these guidelines?

We have colorectal cancer screening recommendations from several agencies, including the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), the American Cancer Society, and the CDC. And so sometimes I think the public has difficulty understanding what would be the best approach when they are faced with so many different choices.

Overall, the recommendation is to get a colonoscopy after reaching the age 50 and if the test result is completely normal, to get screened every ten years. An alternative would be to get a flexible sigmoidoscopy with annual fecal immunochemical test (FIT); a positive result with FIT indicates the need for a colonoscopy. Sigmoidoscopy is a lot cheaper and it doesn’t require anesthesia, but it only covers the left side of the colon; therefore, it is possible to miss abnormalities that might be occurring on the right side of the colon. Furthermore, some agencies place age limits on screening.

Another option is the stool DNA test that is shown to have some efficacy. However, there are some logistical issues with that because you have to collect quite a bit of stool—a gallon of stool—and then you have to store that in your refrigerator before you ship it to the company. These setbacks cause issues with adherence to screening.

But the bottom line is that some screening is better than no screening.

What are the risk factors for colorectal cancer?

There are known risk factors for colorectal cancer, such as family history, a sedentary lifestyle, unhealthy diet, and being overweight. A family history of colorectal cancer can increase the risk by two to threefold. It also appears that there’s been an increase in the rates of colorectal cancer among people below the age of 50, which may simply be because we are screening more so that we are noticing those patients more than we did before; nevertheless, being diagnosed with colorectal cancer at a younger age is of concern.

What are the challenges with prescribing aspirin for the prevention of colorectal cancer?

The USPSTF recently issued a draft statement recommending low-dose aspirin to prevent cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer in adults ages 50 to 59 years whose 10-year cardiovascular risk is 10 percent or greater, who do not have an increased risk for bleeding, who have a 10-year life expectancy, and who can take low-dose aspirin daily, for at least 10 years.

It is important to note that the benefit of taking aspirin or other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) comes with longer-term exposure. One has to take these medications on a regular basis over multiple years (15-20) to achieve a real benefit. However, high doses can lead to ulcers and bleeding problems as aspirin inhibits platelet activity. So, it is important to ensure that people take the right dose on a regular basis to avoid such complications. For those with a history of ulcer disease it is important to speak with their doctors first to learn if aspirin is right for them.

How can precision medicine help colorectal cancer prevention?

With precision medicine approaching the clinic, we are starting to learn in depth the molecular mechanisms that initiate and promote colorectal cancer. Data gathered from analyses of liquid biopsies and tissue biopsies are helping us to more efficiently predict when and how to intervene with prevention approaches.

Can you tell us about your recent research on the role of inflammation in promoting colorectal cancer?

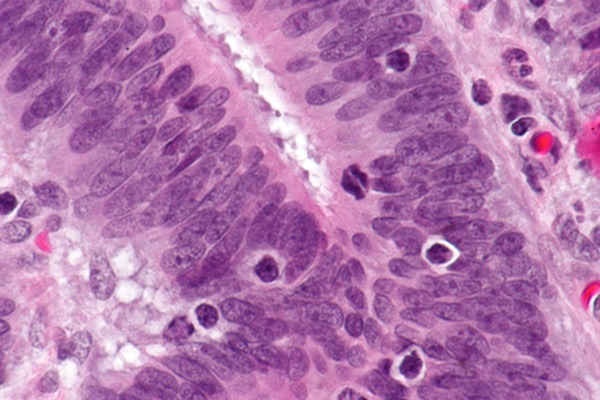

We recently published a paper in Gastroenterology, in which we found that colorectal cancer stem cells proliferate in the presence of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), a hormone-like substance that promotes inflammation. When tested in animal models, colon cancer cells primed with PGE2 were found to metastasize to the liver much more readily. We also found that inhibiting the receptor, EP4, to which PGE2 binds, leads to the inhibition of EP4-receptor-mediated PI3-Kinase and MAP-kinase signaling pathways, which dramatically lowered the metastatic spread of these cancer cells.

We are very excited about our findings and are collaborating with individuals in the pharmaceutical industry who are developing inhibitors to PGE2 receptors. Preliminary studies using animal models look encouraging. We are hopeful about developing a drug that would more precisely target the PGE2 pathway, with the goal of lowering metastatic spread in patients or possibly even in cancer prevention.

How are the drugs that are being developed to target the PGE2 pathway different from existing NSAIDs?

The molecular target and the mechanism of action of the EP4 receptor antagonist we are currently testing in our preclinical studies are completely different from those of the NSAIDs. NSAIDs target the proximal part of the inflammatory pathway called the cyclooxygenase pathway and inhibit the enzymes required for the synthesis of all prostaglandins, including PGE2, PGI2, and PGD2. The EP4 receptor antagonist, on the other hand, is very specific to one of the receptors PGE2 binds to, and does not interfere with the enzymes required for the synthesis of other prostaglandins. This will likely lower the risk of bleeding and cardiovascular side effects dramatically.

What is the prospect of combining aspirin or NSAIDs with immunotherapy to treat colorectal cancers?

Currently there are some limitations to treating colorectal cancers with immune checkpoint inhibitors because so few patients respond to this treatment. We have come to understand that the patients that respond best to immunotherapy are the ones that have tumors with a higher mutational load and with some infiltration of leukocytes.

A recent study published in the New England Journal of Medicine discusses outcomes from a phase II clinical trial, in which patients with defects in enzymes in a DNA repair pathway called the mismatch repair pathway were found to have more lymphocytic infiltrates in their tumors, and were more likely to respond to the immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab (Keytruda). These studies show that the tumor microenvironment plays an important role in determining the outcomes to immunotherapy in colorectal cancers. We are aggressively looking for combinations of immunotherapy and anti-inflammatory drugs that would make immunotherapy applicable to a larger number of colorectal cancer patients.

Our laboratory is currently testing a combination of an immune checkpoint inhibitor with the EP4 receptor antagonist. Preliminary data from preclinical studies look very promising, in that we are seeing better outcomes with the combination than when these agents are tested individually.

What efforts are being made in increasing cancer awareness among the public and narrowing the disparities in colorectal cancer screening and treatment outcomes?

Public education and awareness is key to our fight against cancer. When people go to see their doctor, it is always good to ask about cancer screening and make sure you receive the recommended cancer screening tests so that you can try to avoid being diagnosed with the disease at a late stage, when it is more difficult to treat.

Screening and treatment outcome disparities are areas that the research community is still trying to improve upon. The colorectal cancer screening tests are, for example, covered by most of the providers and with Medicare, but there is a lot of variability in coverage with Medicaid and, as we know, there are some states that haven’t expanded Medicaid coverage as outlined in the ACA, which affects people in the lower socioeconomic class. If Medicaid programs could be expanded across the whole country, which could offer payment for screening in some of these lower socioeconomic groups, it clearly would have an impact on mortality from colorectal cancer.

Efforts are also being made to develop noninvasive blood tests for colorectal cancer with which to cost-effectively screen the whole population, and then, only select those with positive test results to undergo colonoscopy. Such initiatives would not only reduce the costs, but also allow for better, more effective screening approaches. There are several research groups working on this, but presently we do not have a validated test for clinical use.

We need more efforts to try to make sure that all racial and ethnic groups and those in the lower socioeconomic class are better informed about the utility and value of screening in reducing the risk. The challenge is that there are just so many different cancer organizations that exist and I think the public does get inundated with multiple cancer messages that are not always clear or helpful. The AACR Foundation strives to ensure that we educate the public and support innovative cancer discoveries in order to understand, prevent, treat, and cure cancer as effectively as we can.

Raymond DuBois, MD, PhD, served as the 2008-2009 president of the AACR, was inducted as a fellow of the AACR Academy in 2013, and currently serves as the chairman and president of the AACR Foundation. He is also executive director of the Arizona State University (ASU) Biodesign Institute. Among his responsibilities at ASU, DuBois holds the Dalton chair in ASU’s School of Health Solutions, and joint appointments in the Departments of Chemistry and Biochemistry. He also co-leads the Cancer Prevention Program at Arizona’s Mayo Clinic. DuBois previously served as provost and executive vice president of academic affairs at MD Anderson Cancer Center, as well as director of the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center. DuBois is a recognized authority in the molecular and genetic basis for colorectal cancer.