A Need to Increase Awareness of HPV Vaccines and Cervical Cancer Prevention

Cancer awareness months provide an opportunity to increase public knowledge of all aspects of a particular cancer, from prevention, to treatment, to issues surrounding survivorship. This month is Cervical Cancer Awareness Month, and a paper published yesterday in the AACR journal Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, which highlights disparities in uptake of vaccines approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the prevention of cervical cancer, highlights that we need to do more to educate the public about the availability and effectiveness of vaccines that can prevent cervical cancer.

Vaccines for Cervical Cancer Prevention

The discovery that almost all cases of cervical cancer are caused by persistent cervical infection with certain subtypes of human papillomavirus (HPV) led to the development of a number of HPV vaccines. There are currently three HPV vaccines that have been approved by the FDA for preventing cervical cancer and precancers. The FDA approved each based on clinical trials showing that the vaccine effectively prevented cervical precancers caused by the HPV subtypes that it protects against.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend girls and boys ages 11 and 12 receive three doses of an HPV vaccine. The government agency also recommends vaccination for women age up to 26 and men up to age 21 who did not receive the vaccine as a preteen.

Research highlighted in a previous post on this blog suggests that almost 90 percent of invasive cervical cancer cases worldwide could be prevented if all girls and women for whom vaccination is recommended were to be vaccinated with the most recently approved HPV vaccine, Gardasil 9, which protects against seven HPV subtypes known to cause cancer—HPV16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58.

However, data from the 2014 National Immunization Survey–Teen (NIS-Teen)—an annual survey conducted by the CDC to monitor vaccination uptake in the United States—indicate that just 39.7 percent of adolescent girls ages 13 to 17 and 21.6 percent of boys of the same age had received three or more doses of an HPV vaccine. This low vaccine coverage contrasts starkly with coverage for the Tdap vaccine that protects against tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis: 87.6 percent of adolescents ages 13 to 17 have received one or more doses of Tdap.

Disparities in HPV Vaccine Uptake

The authors of the new paper on HPV vaccination published yesterday in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, analyzed data from 20,565 girls ages 13 to 17 who participated in the 2011 and 2012 NIS-Teen to look for geographic differences in HPV vaccine uptake. They found that adolescent girls living in high-poverty communities and majority Hispanic communities were more likely to have received at least one dose of an HPV vaccine than those living in low-poverty communities and in communities of other racial and ethnic compositions.

A closer look at the data show that the highest HPV vaccine initiation rate was among girls living in communities where the majority of the population was Hispanic (69 percent), and the lowest rate was among girls living in majority non-Hispanic white communities (50 percent). In addition, the odds of HPV vaccine initiation among girls living in communities where 20 percent or more of the population was living below the poverty level were 1.18 times greater than for those living in the least impoverished communities.

Kevin A. Henry, PhD, first author of the Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention study titled, “Geographic Factors and Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccination Initiation Among Adolescent Girls in the United States.”

The first author of the study, Kevin A. Henry, PhD, an assistant professor in the Department of Geography and Urban Studies at Temple University in Philadelphia and member of Fox Chase Cancer Center’s Cancer Prevention and Control program, said in a press release, “Our findings that the rates of HPV vaccine initiation are highest among adolescent girls living in high-poverty communities and majority Hispanic communities, which generally have higher than average poverty rates, are contrary to conventional beliefs that socioeconomic disadvantage is a barrier to health care. It is possible that the availability of safety-net immunization services, such as the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) or Medicaid health insurance for these populations, and their access to HPV vaccines through the Vaccines for Children (VFC) program, may be contributing to the higher HPV vaccine uptake.”

Henry also noted that the findings are encouraging because these same communities often have higher cervical cancer rates. But, he cautioned that continued cervical cancer screening of vaccinated and unvaccinated women is needed because the vaccine does not cover all cancer-causing HPV types and sexually active women could have been infected prior to vaccination.

Increasing Awareness: Beyond the Public

Studies like the one conducted by Henry and colleagues, which identify disparities in HPV vaccine uptake, provide important information to individuals developing public health education messages to promote HPV vaccine uptake. Results from these types of studies distinguish between those who might be more receptive to current education approaches and those for whom improvements are clearly needed.

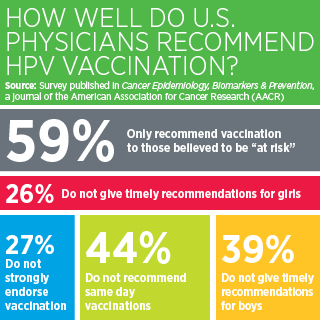

However, another study published in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention late last year showed that it might be possible to increase HPV vaccine uptake by better educating healthcare providers on how to communicate with parents in ways that encourage HPV vaccination.

The first author of that study, Melissa B. Gilkey, PhD, assistant professor of population medicine at Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute in Boston, said in a press release, “We were surprised that physicians so often reported recommending HPV vaccination inconsistently, behind schedule, or without urgency. Of the five communication practices we assessed, about half of physicians reported two or more practices that likely discourage timely HPV vaccination.”

Gilkey added, “We are currently missing many opportunities to protect today’s young people from future HPV-related cancers. Helping providers communicate about the HPV vaccine effectively is a promising strategy for getting more adolescents vaccinated.”

Gilkey added, “We are currently missing many opportunities to protect today’s young people from future HPV-related cancers. Helping providers communicate about the HPV vaccine effectively is a promising strategy for getting more adolescents vaccinated.”

The most recent estimates are that 12,990 U.S. women will be newly diagnosed with cervical cancer in 2016 and that 4,120 will die from the disease. Therefore, we hope that the information garnered from the research highlighted here will help increase awareness of the potential for cervical cancer prevention through HPV vaccination and will lead to dramatically decreased cervical cancer incidence in the coming years.