Why Does Immunotherapy Not Benefit Everyone Long-term?

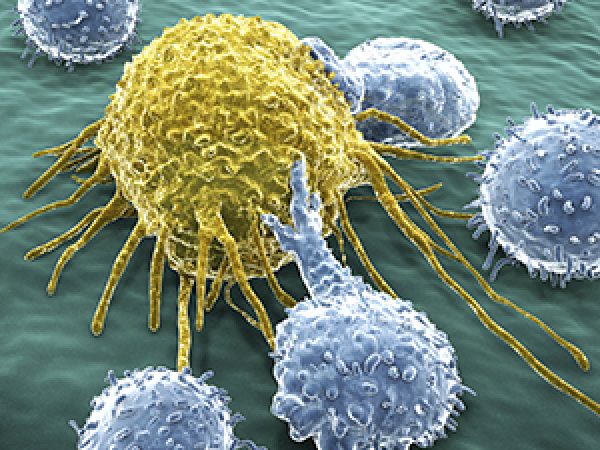

Immunotherapy is revolutionizing the treatment of cancer. As discussed in an earlier post on this blog, immunotherapeutics that work by taking the brakes off immune cells called T cells have been particularly transformational, dramatically improving outcomes for some patients with an increasing array of cancer types. But what about those patients whose cancers do not respond to these immunotherapeutics, and what about those whose cancers respond initially but then progress after becoming resistant to the treatments?

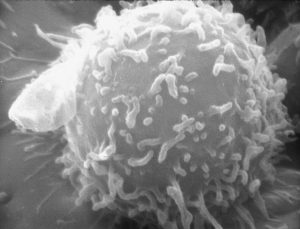

Electron microscopic image of a single human lymphocyte. Many FDA-approved immunotherapeutics work by taking the brakes off immune cells called T cells or T lymphocytes, allowing them to fight cancer. Photo provided by the National Cancer Institute.

Identifying ways to help these individuals is the focus of an increasing number of researchers.

Here, I outline the challenge that these researchers are trying to overcome and highlight two recent studies that point toward potential ways to overcome the issues. Both these studies are funded in part by a Stand Up To Cancer–Cancer Research Institute Cancer Immunology Dream Team Translational Research Grant. The American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) is the Scientific Partner of Stand Up To Cancer, which is a program of the Entertainment Industry Foundation.

What is the problem?

There have been many stories of success with immunotherapy. Take the story of Donna Fernandez, who was diagnosed with stage 4 lung cancer in 2012. After her cancer did not respond to chemotherapy she opted to participate in a clinical trial testing the immunotherapeutic nivolumab (Opdivo), and is now living life like she did before her diagnosis.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R-zeFz8ng_I

A recent study, which was highlighted previously in a post on this blog, showed that more than a third of patients with metastatic melanoma who received nivolumab, an immunotherapeutic that works by releasing the PD-1/PD-L1 brake on T cells, are still alive five years after starting treatment. This number is extremely exciting given that the National Cancer Institute calculates that the five-year relative survival rate for all patients with metastatic melanoma diagnosed between 2005 and 2011 was just 17 percent.

Despite the obvious cause for excitement, this means that about two-thirds of patients with metastatic melanoma who were treated with nivolumab had cancer that did not respond to the immunotherapeutic or progressed after initially responding.

How can we help nonresponders?

A recent study published in the AACR journal Cancer Immunology Research reports on efforts by Suzanne L. Topalian, MD, professor of surgery and oncology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and director of the Melanoma Program at the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center in Baltimore, Maryland, to address the issue of nonresponse to immunotherapeutics targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 brake on T cells.

“Between 15 and 30 percent of patients with renal cell carcinoma, the most common type of kidney cancer, have substantial and durable responses to immunotherapeutics that target the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, such as nivolumab,” said Topalian, who is also associate director of the Bloomberg~Kimmel Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy at Johns Hopkins, in a news release. “Researchers are now trying to identify markers that can predict whether or not a patient is likely to respond to these treatments, so that those who are unlikely to respond are saved the time and can avoid the potential adverse effects of a treatment unlikely to benefit them.”

Topalian explained that some prior studies suggest that renal cell carcinomas positive for PD-L1 are more likely to respond to PD-1 pathway blockers compared to those negative for PD-L1, but that not all PD-L1–positive renal cell carcinomas respond to these immunotherapies.

As a result, she and her colleagues focused their analysis on archived pretreatment tumor samples from 13 patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma positive for PD-L1 who had gone on to receive nivolumab through clinical trials. Four of these patients were classified as having responded to nivolumab treatment and nine were classified as having not responded.

They identified 110 genes that were expressed at significantly elevated levels in tumors from nonresponding patients and found that many of these genes were associated with metabolism, the chemical processes that generate energy and eliminate waste products in cells.

“If these data are reproduced in larger groups of patients, we could potentially use the information to guide treatment decisions for patients with renal cell carcinoma,” said Topalian.

She also noted that the researchers are looking to extend these studies to analyze other types of cancer, as well as to confirm the current results in additional renal cell carcinomas from patients receiving anti–PD-1 therapies. “Such studies may also reveal new drug targets for combination therapies with anti–PD-1,” said Topalian.

How can we help patients whose cancer becomes resistant to immunotherapy after initially responding?

If we are to address the issue of the emergence of resistance to immunotherapeutics targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 brake on T cells, it is imperative that we understand the mechanisms underpinning the acquisition of resistance. This knowledge has the potential to point to combination treatments that could be used after resistance has developed or even to prevent it emerging in the first place.

A paper published recently in The New England Journal of Medicine reported efforts to understand mechanisms of melanoma resistance to the anti–PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab (Keytruda) by a team of researchers led by Antoni Ribas, MD, PhD, professor of medicine, surgery, and molecular and medical pharmacology at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and director of the Tumor Immunology Program at the UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Ribas, who is also a member of the AACR Board of Directors, and his colleagues analyzed serial tissue samples taken from four patients who had metastatic melanoma that had initially responded to treatment with pembrolizumab but had then progressed. The samples analyzed were taken prior to pembrolizumab treatment and after disease progression.

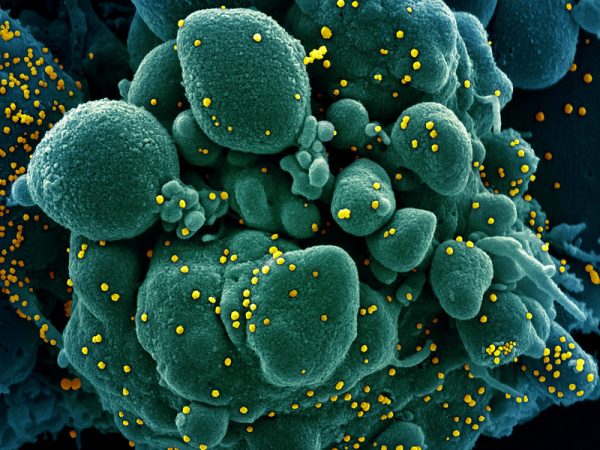

In samples from two of the four patients, the researchers found that resistance was associated with loss-of-function genetic mutations in JAK1 or JAK2, which made the cancer cells less sensitive to one of the immune system molecules that help fight the cancer, a molecule called interferon-ɣ. In one of the other patients, the acquisition of resistance was associated with a mutation in the β2m gene that impaired the ability of T cells to recognize the cancer cells.

The first author of the study, Jesse Zaretsky, who is a doctoral student in Ribas’ laboratory, told The Washington Post that the fact that the fourth patient’s tissue didn’t have those genetic alterations indicates that other mechanisms of resistance may be discovered in the future.

What is next?

These studies provide some of the earliest insights into the reasons why some patients do not respond to immunotherapeutics targeting PD-1 or respond at the beginning and later relapse. This is an important area of research and one that we will likely hear a lot about at the International Cancer Immunotherapy Conference, which is being hosted by the Cancer Research Institute (CRI), the Association for Cancer Immunotherapy (CIMT), the European Academy of Tumor Immunology (EATI), and the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) in New York, Sept. 25–28.

It’s great that two-thirds of patients who suffer from metastatic melanoma and tried Immunotherapy have benefited from it because of initially responding. One of my aunts has cancer, and she was recommended to try nivolumab and see if it will help her condition. I will send these details to my cousin so they can look for a specialist that will evaluate my aunt for Immunotherapy.