Increasing Awareness of Breast Cancer Health Disparities

The phrase “Knowledge is power” is often attributed to the 16th century English philosopher Francis Bacon. Despite its age, the phrase is relevant to the cancer community today. It underpins the concept of cancer awareness months, which provide an opportunity to increase the public’s knowledge of all aspects of a particular cancer, from the latest ways to prevent it, detect it, and treat it, to issues surrounding survivorship.

This month is Breast Cancer Awareness Month, a type of cancer against which we have made much progress, as exemplified by National Cancer Institute statistics showing that the overall U.S. age-adjusted breast cancer death rate has been falling since the late 1980s. The breast cancer death rate dropped from 33.2 deaths per 100,000 U.S. women in 1989 to 20.7 deaths per 100,000 U.S. women in 2013, the last year for which data are currently available.

However, a recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) highlights that the progress we are making has not been uniform for all segments of the population. The report shows that although overall U.S. age-adjusted breast cancer death rates have been falling, breast cancer death rates are about 40 percent higher among black women compared with white women (28.2 deaths per 100,000 black women compared with 20.3 deaths per 100,000 white women).

This disparity in breast cancer mortality has been increasing in recent years because breast cancer death rates decreased faster among white women (−1.9 percent per year) compared with black women (−1.5 percent per year) from 2000 to 2014.

The breast cancer mortality disparity is concerning because the report shows that although U.S. breast cancer incidence rates decreased among white women from 1999 to 2013, falling from 138.1 per 100,000 to 124.4, they increased slightly among black women during the same period, rising from 117.3 per 100,000 to 122.9.

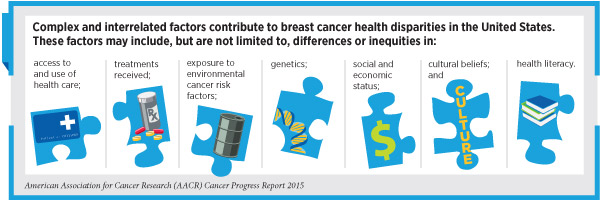

Complex and interrelated factors contribute to breast cancer health disparities in the United States. As a result, a multifaceted approach is needed to address the challenge. One facet is to raise awareness of the issue. Another is to investigate how biological factors, such as a woman’s genetics, contribute to the differences in breast cancer risk and outcomes among different segments of the population.

One such study was presented at the recent Ninth AACR Conference on The Science of Cancer Health Disparities in Racial/Ethnic Minorities and the Medically Underserved. Through their work, the researchers found that triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) in African-American women is much more likely to lack the androgen receptor protein compared with TNBC in European-American women, and that this may contribute to the racial disparity in survival outcomes among African-American and European-American women with TNBC.

Another study to investigate how genetic and biological factors contribute to breast cancer risk among black women was launched earlier this year by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). According to the NCI, the Breast Cancer Genetic Study in African-Ancestry Populations initiative will be the largest-ever study of breast cancer genetics in black women. The agency went on to explain that as part of the study, the genomes of 20,000 black women with breast cancer will be compared with those of 20,000 black women who do not have breast cancer. The data will also be compared with that generated from analysis of the genomes of white women who have breast cancer.

Although it will be a while before the Breast Cancer Genetic Study in African-Ancestry Populations initiative yields data, we look forward to hearing results from other researchers working in this burgeoning field at the 2016 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, which is being held Dec. 6–10, in San Antonio.

For more information about the 2016 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, including how to register, click here.