Second CAR T–cell Therapy Approved by the FDA

Last week, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the second of a revolutionary new type of immunotherapy known as chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T–cell therapy.

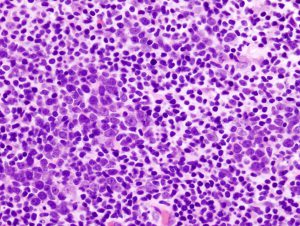

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is the most common type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma diagnosed in the United States. Image via Wikimedia.

The CAR T–cell therapy, which is called axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta), was approved for treating adults with certain types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma whose disease has progressed despite them having tried at least two other kinds of treatment. Specifically, it was approved for treating diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, high grade B-cell lymphoma, and DLBCL arising from follicular lymphoma.

Different types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma grow and spread at different rates. Those that grow and spread rapidly are referred to as aggressive lymphomas. All the types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma for which axicabtagene ciloleucel is approved are aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomas. DLBCL is the most common of these diseases. It accounts for about 30 percent of new cases of non-Hodgkin lymphoma diagnosed in the United States, according to the National Cancer Institute, which means there will be an estimated 21,672 new cases of DLBCL diagnosed in this country in 2017.

All the types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma for which axicabtagene ciloleucel is approved arise in immune cells called B cells, which almost always have a protein called CD19 on their surface.

Axicabtagene ciloleucel targets CD19-positive cells. Each patient’s axicabtagene ciloleucel treatment is customized using immune cells called T cells harvested from his or her blood. Once the T cells have been harvested, they are genetically modified to have a new gene that encodes a protein called a CAR, which is why this type of treatment is often referred to as cell-based gene therapy. After the T cells are modified, they are expanded in number and then infused back into the patient.

The external facing portion of the CAR in axicabtagene ciloleucel recognizes and attaches to CD19 on the surface of the non-Hodgkin lymphoma B cells, which causes the internal facing portion of the CAR to trigger a signaling network that results in the CAR T cells attacking the cancer cells.

The approval of axicabtagene ciloleucel was based on results from 101 patients enrolled in the phase I/II ZUMA-1 clinical trial. According to the FDA statement, 51 percent of the patients who were treated with axicabtagene ciloleucel had complete remission, meaning there was no cancer detectable during at least one follow-up examination. Additional data from this trial were presented earlier this year at the AACR Annual Meeting 2017. These data showed that 39 percent of the 101 patients remained in complete remission after a median of 8.7 months.

Like the first CAR T–cell therapy approved by the FDA, tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah), axicabtagene ciloleucel can cause serious adverse effects, and the approval comes with a boxed warning for cytokine-release syndrome and neurological toxicities. It is also being approved with a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy that requires that health care facilities using the new treatment be specially certified, with staff trained to recognize and manage cytokine-release syndrome and neurologic events.

The huge concern around the serious adverse effects of CAR T–cell therapy is evident from the amount of research being undertaken to find new ways to mitigate these effects and to discover biomarkers that could help identify those patients for whom the risks of these effects are increased. In this regard, the authors of one study recently published in the AACR’s journal Cancer Discovery, have developed a predictive classification tree algorithm to identify patients, within the first 36 hours after CAR T–cell infusion, who are at increased risk for severe neurotoxicity.

The lead author of the study, Cameron J. Turtle, MBBS, PhD, associate member at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, associate professor at the University of Washington, and attending physician on the Immunotherapy Service at Fred Hutch, said in a news release that patients at increased risk for this adverse event may benefit from early intervention, but more studies are required.