FDA Approves First Targeted Therapeutic for BRCA-mutant Breast Cancer

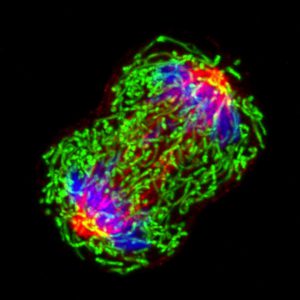

The image shows a dividing triple-negative breast cancer cell. Triple-negative breast cancers occur at an elevated frequency among women with breast cancer harboring an inherited BRCA1 mutation. Image courtesy of National Cancer Institute.

On Friday, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the molecularly targeted therapeutic olaparib (Lynparza) for treating certain patients with metastatic, HER2-negative breast cancer. The FDA also granted marketing authorization for a test to identify those patients eligible to receive olaparib: patients with an inherited, cancer-associated BRCA1 or BRCA2 (BRCA1/2) mutation.

Before this approval, there were no molecularly targeted therapeutics approved for treating HER2-negative breast cancer with an inherited BRCA1/2 mutation. For those patients whose disease was also hormone receptor–positive, endocrine therapy was an option. However, chemotherapy was the only treatment option for those whose disease lacked the hormone receptor and was said to be triple-negative.

About 5 to 10 percent of all breast cancers diagnosed in the United States are attributable to an inherited BRCA1/2 mutation, according to the National Cancer Institute. These mutations also account for about 15 percent of ovarian cancer cases.

A key function of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 proteins is to repair damaged DNA through a process called homologous recombination. Cancer-associated BRCA1/2 mutations cause cells to be deficient in this process, leading to the accumulation of genetic mutations and, sometimes, cancer.

As discussed in a previous post on this blog, researchers have discovered that cells with a cancer-associated BRCA1/2 mutation often rely on a second pathway, called the base excision repair pathway, to repair DNA. They have also found that blocking the function of proteins called poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) proteins, which are involved in the base excision repair pathway, can cause cells with cancer-associated BRCA1/2 mutations to die.

These discoveries provided the rationale for testing PARP inhibitors as a treatment for patients with cancers harboring inherited BRCA1/2 mutations. The first clinical trials to yield results that supported FDA approvals involved patients who had ovarian cancer. There are three PARP inhibitors approved for treating certain women who have ovarian cancer with an inherited BRCA1/2 mutation—olaparib, rucaparib (Rubraca), and niraparib (Zejula). Rucaparib can also be used to treat ovarian cancer with a BRCA1/2 mutation acquired during the patient’s lifetime and niraparib can be used to treat both BRCA1/2 mutation–positive and –negative ovarian cancers.

The randomized phase III OlympiAD clinical trial is the first clinical trial testing a PARP inhibitor as a treatment for patients who had breast cancer harboring an inherited BRCA1/2 mutation to yield results that supported an FDA approval. Results from the trial, which were published last year in The New England Journal of Medicine, showed that the median progression-free survival was 2.8 months longer among the 205 patients who received olaparib compared with the 97 patients who received chemotherapy of their physician’s choice—capecitabine, eribulin, or vinorelbine. The results translated into a 42 percent lower risk of death or disease progression for those receiving olaparib.

Results from the OlympiAD clinical trial also provided the basis for the FDA to grant marketing authorization for the BRACAnalysis CDx test for use as an aid in identifying patients with breast cancer with inherited cancer-associated BRCA1/2 mutations who may be eligible for olaparib.

Other PARP inhibitors, including rucaparib, niraparib, and an investigational therapeutic called talazoparib, are being evaluated in clinical trials as potential treatments for patients who have breast cancer harboring an inherited BRCA1/2 mutation. If the results of these trials are as positive as those recorded for olaparib in the OlympiAD trial, it is likely that we will see additional molecularly targeted therapeutics approved for treating BRCA1/2 mutation–positive breast cancer in the near future.

In addition, as discussed in a recent post on this blog, preclinical studies have shown that PARP inhibitors may be effective against breast cancers with alterations in homologous recombination genes other than BRCA1 and BRCA2. Clinical trials testing this hypothesis have been launched, and we look forward to learning the results of these in due course.