Malignancy, MSI Status, and the Microbiome

The human microbiome – the collection of bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other microorganisms that live inside and on the surface of our bodies – has garnered significant scientific interest in recent years. The Human Microbiome Project (HMP), which was launched in 2007, seeks to characterize the diverse microbiota to help understand how these microbes impact human health and disease. Results from the HMP predict that over 10,000 microbial species coexist within the human ecosystem.

One of the most diverse areas of the human microbiome can be found in the gut. While each individual has a unique composition of gut microbes, alterations to the microbiome can affect our health and may even influence the effectiveness of certain anticancer therapeutics, explained Marios Giannakis, MD, PhD, a medical oncologist and assistant professor of medicine at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and a co-senior author of a recent paper published in Cancer Immunology Research, a publication of the American Association of Cancer Research (AACR).

“The cancer microbiome is being increasingly appreciated as an important component of the tumor microenvironment, and the gut is an area that has a high degree of colonization with many different microbial species,” Giannakis said. “The gut microbiome has been shown to impact the effectiveness of chemotherapy and immunotherapy agents in animal models and in patients, and the impact of the gut microbiome on cancer incidence and progression is an area of active investigation,” he noted.

“There are several ways through which alterations in the microbiome may impact cancer development and outcome,” explained Shuji Ogino, MD, PhD, MS, professor of pathology at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and senior author of the aforementioned study. “The microbiome can elicit an inflammatory reaction, which in turn can initiate or accelerate carcinogenesis, interfere with an effective antitumor immune response, and promote growth or facilitate distant metastases. In addition, even after the cancer has developed, changes in the gut microbial composition may affect the prognosis of patients and the efficacy and toxicity of cancer therapies,” he said.

In their recent study, Giannakis and Ogino wanted to determine how the common oral bacterium Fusobacterium nucleatum can affect immune response patterns in colorectal tumors.

F. nucleatum and colorectal cancer

“While F. nucleatum can been found in healthy tissues, it is also associated with periodontal disease and other infections. In addition, this bacterium has been implicated in colorectal carcinogenesis,” Giannakis explained.

“Multiple studies have demonstrated an enrichment of F. nucleatum in colorectal tumors and adenomas relative to normal colon tissue,” he noted. “Furthermore, we have previously demonstrated an inferior prognosis for patients whose colorectal tumors are positive for F. nucleatum, and experimental studies indicate that this bacterium can augment tumor growth, yet the exact mechanisms are incompletely understood.”

The authors have also shown that F. nucleatum is often found in colorectal tumors that have high microsatellite instability (MSI). “MSI-high tumors, which have an impaired DNA mismatch repair pathway, are hypermutated and consequently have a high number of neoantigens,” Giannakis said. As a result, MSI-high cancers are often more responsive to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Indeed, last year the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the use of pembrolizumab (Keytruda) for patients with MSI-high/mismatch repair-deficient solid tumors whose disease has progressed despite prior treatment, which was explained in detail in a previous post on this blog.

“It is important to point out, however, that responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors are not universal among MSI-high cancers,” noted Giannakis. “In fact, only 30-55 percent of patients with MSI-high tumors exhibit a response when treated with immune checkpoint blockade despite a universally high neoantigen load.”

F. nucleatum, immune response, and MSI status

In their current study, the authors evaluated the association of F. nucleatum with immune response in MSI-high and non-MSI-high tumors. Utilizing tumor samples from more than 1,000 colorectal cancer patients, the researchers measured levels of F. nucleatum DNA and assessed immune response via histopathologic lymphocytic reactions. Tumors were classified as MSI-high if instability was present in at least 30 percent of microsatellite markers as measured via polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Of the 1,041 cases, 864 were classified as non-MSI-high and 177 were classified as MSI-high. F. nucleatum DNA was found in 135 patient samples (13 percent of all evaluated tumors). Thirty-three percent of MSI-high tumors were positive for F. nucleatum, while only nine percent of non-MSI-high tumors were positive for this bacterium.

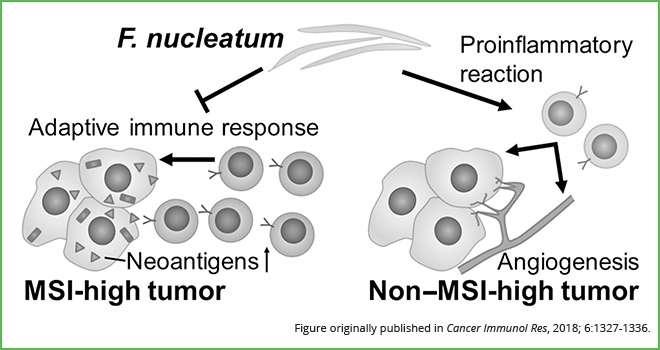

Following multivariable analysis, the authors found that in non-MSI-high tumors, the presence of F. nucleatum was positively correlated with immune response, as observed by an increase in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and intratumoral periglandular reactions. Conversely, in MSI-high tumors, the presence of F. nucleatum was negatively correlated with immune response, accompanied by a decrease in the same lymphocytic reaction patterns.

“Our findings suggest that F. nucleatum may be having a differential role in tumor immunity according to MSI status in colorectal cancer,” Ogino said. “This bacterium may play a pro-inflammatory role in non-MSI-high colorectal cancers and an immunosuppressive role in MSI-high colorectal cancers,” he explained. “More generally, this finding further supports the need to systematically investigate the role of Fusobacterium and the microbiome in colorectal cancer pathogenesis and tumor immunity.”

Results from this study suggest that F. nucleatum promotes immunosuppressive responses in MSI-high colorectal tumors and pro-inflammatory responses in non-MSI-high colorectal tumors.

Microbiome modulation to enhance immunotherapy efficacy

Composition of the gut microbiome has influenced immunotherapy responses in pilot studies of patients with melanoma, lung, and kidney tumors. “A predictive role for the microbiome in immunotherapy and how to manipulate it for the benefit of patients are areas that are worth studying,” noted Giannakis. “Our study suggests that we need to further investigate the interplay between cancer, immunity, and the microbiome to help expand the use of immunotherapies in colorectal cancer.”

“It will be interesting to investigate the presence of F. nucleatum and its impact on the immune microenvironment in non-MSI-high tumors to improve response to immunotherapies,” said Ogino. “On the other hand, the immunosuppressive effect that F. nucleatum has in MSI-high colorectal cancers raises questions about its possible effect on resistance to checkpoint blockade, where the response is not universal.”

This rationale was echoed in an accompanying commentary which also predicts that clinical trials involving fecal transplants, dietary modifications, and drugs that alter the gut microbiome (such as antibiotics and probiotics) will increase dramatically in the coming years.

Interested in learning more about the microbiome? An entire plenary session that discusses recent advances in microbiome research will be presented at the upcoming AACR Tumor Immunology and Immunotherapy meeting, taking place Nov. 27-30.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pa0NVM9aHYU