What are the Side Effects of Immunotherapies and How Do They Arise?

Immune-related adverse events (irAEs) is the collective term used to describe the side effects that arise in response to activation of the immune system by immunotherapies. As this class of cancer treatment yields undisputed effectiveness in cancer patients who respond, a recent focus has been to reduce the irAEs without impeding treatment response.

Immunotherapies, particularly immune checkpoint inhibitors, have taken the concept of treating cancers to the next level, by targeting the cancer patients’ immune cells rather than their cancer cells. Immune checkpoint inhibitors release the brakes on T cells, so they can mount an effective immune attack on cancer cells. The immune checkpoint inhibitor ipilimumab (Yervoy) targets the checkpoint protein CTLA-4, while pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and nivolumab (Opdivo) target the checkpoint protein PD-1. Some, such as atezolizumab (Tecentriq) and avelumab (Bavencio), target the protein PD-L1 present on cancer cells and prevent them from engaging the PD-1 protein on T cells, thereby disrupting the PD-1/PD-L1 axis and releasing the brakes on T cells.

The success of this class of therapeutics can be gleaned from the fact that between 2011 and 2018, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved seven immune checkpoint inhibitors to treat 20 different types of cancers, including melanoma, lung cancer, head and neck cancer, bladder cancer, cervical cancer, liver cancer, stomach cancer, and lymphoma, and for treating patients with any type of solid tumor that is microsatellite instability–high or mismatch repair–deficient.

Understanding irAEs

With the advent of immunotherapy, oncologists and cancer researchers accustomed to the familiar, decades-old set of toxic side effects from chemotherapies and radiotherapy are being challenged with understanding and defining a new set of short-term and long-term side effects, referred to as irAEs, to provide timely and effective remedies to cancer patients experiencing them.

Fifty or more percent of patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors experience some side effects, from rash and local inflammation that can be treated with steroids and/or by temporarily discontinuing the treatment, to severe side effects, such as type 1 diabetes (T1D), thyroid and cardiac issues. While the incidence of adverse events is high, the severity varies, with only a small percentage of patients experiencing serious side effects, explains Jeffrey A. Bluestone, PhD, president and chief executive officer of the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy; and A.W. and Mary Margaret Clausen Distinguished Professor of Metabolism and Endocrinology and Director of the Hormone Research Institute in the Diabetes Center at University of California San Francisco.

In a paper Bluestone and colleagues published in the AACR journal Cancer Immunology Research, they note that irAEs are either a consequence of an autoinflammatory response, caused by the activation of innate immunity, or an autoimmune response, indicated by the presence of autoantibodies and antigen-specific memory T-cell responses.

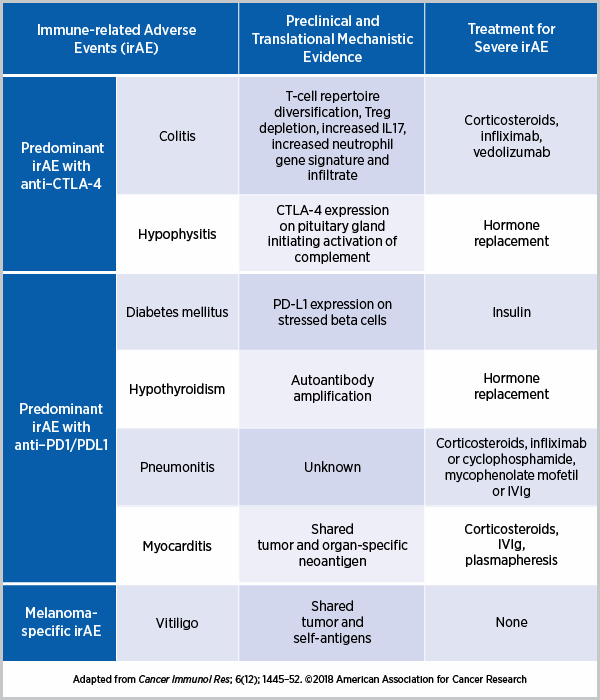

The autoimmune reactions caused by immune checkpoint inhibitors appear to be dependent on the pathways targeted, as explained in a paper published in Nature Medicine. For example, since CTLA-4 is present in the pituitary gland, patients treated with anti–CTLA-4 often develop hypophysitis, an autoimmune disease of the pituitary gland, but this side effect is rare in patients treated with anti–PD1. Whereas the predominant irAEs with anti–CTLA-4 are colitis and hypophysitis, treatment with an anti-PD1/PD-L1 can cause T1D, hypothyroidism, pneumonitis, and myocarditis, among others. Some irAEs, such as thyroid disease, are treatable and the damage reversible; T1D, on the other hand, in which the insulin-producing beta cells are destroyed, is potentially irreversible. Several research groups have attempted to delineate the underlying mechanisms of irAEs, as curated by the authors of the Cancer Immunology Research paper below.

Distinguishing spontaneous autoimmunity from immunotherapy-induced autoimmunity

Autoimmunity is immune responses against our own cells. In some people, these responses cause a range of autoimmune diseases, such as vitiligo, rheumatoid arthritis, and thyroiditis. One approach to addressing and managing irAEs is to differentiate this conventional autoimmunity from immunotherapy-induced autoimmunity.

“I think we are at the very early stages of trying to understand many of the aspects of induced autoimmunity after treatment with checkpoint inhibitors as it compares to ‘conventional’ autoimmunity,” notes Bluestone. He and colleagues point to some of these differences.

For instance, unlike patients with conventional rheumatological autoimmune disorders, patients with disorders induced by anti–PD-1/PD-L1 are negative for rheumatoid factor and other associated proteins, such as cyclic citrullinated protein antibodies. As another example, more than 90 percent of the cases with conventional T1D are positive for autoantibodies against islet-associated antigens, as opposed to less than half of the cases induced by anti–PD-1/ PDL1. Further, the T1D high-risk HLA allele DR4, but not DR3, is more prevalent in patients with immunotherapy-induced diabetes compared with reported frequencies in patients who develop spontaneous T1D.

Whether this means that the irAE happened so quickly that the patients had not yet developed autoantibodies or that different targets and antigens are being recognized, “these are all outstanding and important questions,” says Bluestone. Screening for alternate antibodies in instances where autoantibodies associated with the conventional disease are absent is essential to understand the underlying mechanisms behind these irAEs for further management.

Another outstanding question Bluestone introduces is whether some of the patients experiencing specific irAEs have some aspects of the disease prior to immunotherapy (pre-existing condition) such that the treatment exacerbates it. “Only after we examine the genetics, immune cells, and phenotypic markers in the patients before they get the treatment can we fully understand that,” he notes.

Treating irAEs without compromising cancer treatment response

One important challenge with treating irAEs is ensuring that the approaches do not interfere with antitumor responses. Understanding the interactions between treatment-induced autoimmunity and antitumor immunity is key to developing treatments for irAEs. For example, a common treatment for irAEs is corticosteroids. In one study, among patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with anti-PD-1/PD-L1, those who received corticosteroids to manage their irAE had reduced clinical benefit from immunotherapy, with shorter progression-free survival and overall survival. Several other studies have not observed this association, suggesting the need for more knowledge in this area.

Bluestone and colleagues note that it is important to understand the mechanisms through which corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive agents used to treat irAEs—such as infliximab, vedolizumab, cyclophosphamide, and others—interact with different players in the immune system, in order to achieve optimal effectiveness against irAEs without compromising antitumor immune response.

Understanding and addressing irAEs is a pressing issue for another reason as well: given that only about a third of cancer patients respond to immune checkpoint inhibitors, research labs and pharmaceutical companies are doubling down on efforts to expand the efficacy to more patients, and one of the approaches is to combine different immunotherapeutics to target different pathways.

In their paper in Nature Medicine, Bluestone; CAR T-cell therapy pioneer Carl H. June, MD; and Jeremy Warshauer, MD, note that they expect the incidence and severity of irAEs to increase with the complexity and duration of combination therapies. They add that as immunotherapies are being more commonly utilized as first- and second-line treatments, “immunotoxicity and autoimmunity are emerging as the Achilles’ heel of immunotherapy.”

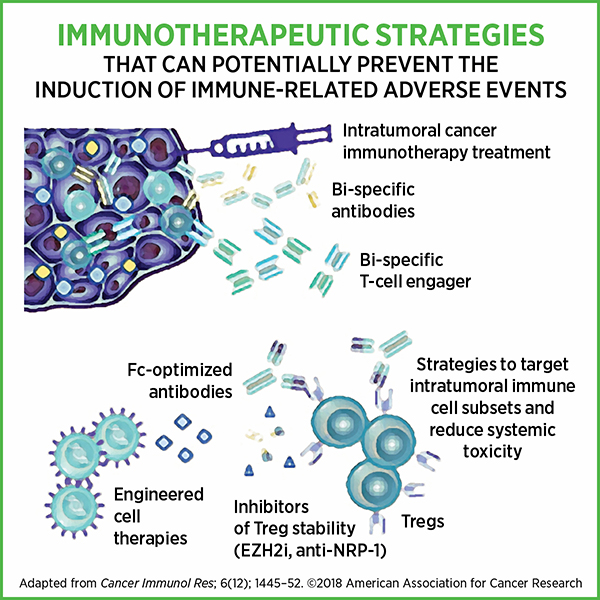

In their Cancer Immunology Research paper, Bluestone and colleagues briefly discuss immunotherapeutic strategies that can potentially prevent irAEs, such as targeting intratumoral T cells directly, using bispecific antibodies to enhance localized targeting of tumor, and using engineered cell therapies to fine-tune immune cell responses. Actively identifying patients who are susceptible to irAEs could help monitor them, provide appropriate care, and prevent complications from potentially life-threatening irAEs while ensuring optimal cancer treatment response.

“I think the biggest challenge for those of us working in this field is not to throw the baby out with the bathwater,” Bluestone cautions. “Immune checkpoint inhibitors are extraordinarily innovative, successful drugs that are changing the face of cancer therapy. The side effect and adverse event issues are real, they are important, they need to be addressed in the long run as we get even more potent immunotherapies, but they should not be perceived at the moment as reasons to not take immunotherapeutics because the drugs themselves have such a positive impact on cancers in certain settings.”