Colorectal Cancer: Preventive Measures, a New Treatment Approach, and Mortality Disparities

The incidence of colorectal cancer – the fourth most common cancer diagnosed in the United States – has been steadily declining since the late 1990s. Despite this decrease, it is estimated that the lifetime risk of developing the disease is roughly one in 20 for those living in the United States. If the cancer is caught early when it is still localized, the five-year relative survival is almost 90 percent. However, if diagnosed after it has metastasized, the five-year relative survival is less than 15 percent.

March is Colorectal Cancer Awareness Month. Read on to learn about risk factors and prevention, a new treatment approach for certain patients with metastatic disease as described in the AACR journal Clinical Cancer Research, and a look at disparities in colorectal cancer mortality as presented at the 12th AACR Conference on The Science of Cancer Health Disparities in Racial/Ethnic Minorities and the Medically Underserved.

Risk factors and preventive measures

A variety of factors can increase your risk for colorectal cancer. A major component is age, as roughly 90 percent of diagnoses occur in those aged 50 or older. However, research has shown that early-onset colorectal cancer is on the rise.

Men are at a higher risk of developing colorectal cancer compared with women. Race also plays a role in disease incidence: blacks have an increased risk of developing colorectal cancer compared with whites. Additionally, a family history of the disease, or having an inflammatory bowel disease (such as ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease) can also increase your risk.

A host of modifiable lifestyle factors can also contribute to colorectal cancer incidence. These include obesity, tobacco use, alcohol consumption, and a diet high in processed meats.

One major way to prevent colorectal cancer is to get screened for the disease, as screening procedures can identify and remove polyps before they become cancerous. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that those aged 50 to 75 at average risk should be screened for colorectal cancer, and some professional societies recommend starting regular screening before the age of 50. Despite this, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that only half of adults in their early 50s (ages 50-54) are up-to-date on their colorectal cancer screening.

A new treatment approach for metastatic colorectal cancer

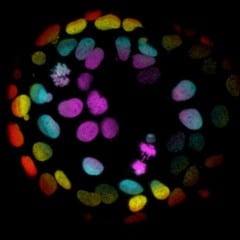

It is estimated that between 8 and 12 percent of metastatic colorectal cancer cases harbor a mutation in the BRAF gene. Mutations to BRAF can result in its constitutive activation, resulting in unchecked signaling of the MAPK pathway, which regulates key cellular processes, such as proliferation. This can lead to uncontrolled cellular growth and can foster cancer progression.

In cancer, the most common mutations to BRAF occur at valine 600 (V600); these mutations are known as class 1 BRAF mutations. Non-V600 BRAF mutations can be divided into two classes – those that are RAS independent (class 2 BRAF mutations), and those that have enhanced binding to RAS and the kinase CRAF, resulting in increased RAS-dependent signaling (class 3 BRAF mutations).

A study published in Clinical Cancer Research sought to determine whether non-V600 BRAF-mutant colorectal cancer tumors, which may not respond to RAF inhibitors, would respond to anti-EGFR therapy. The researchers retrospectively analyzed data from 40 patients with metastatic colorectal cancer – 12 patients with class 2 BRAF mutations, and 28 patients with class 3 BRAF mutations – treated with an anti-EGFR therapy.

Overall, the researchers found that 50 percent of patients harboring class 3 BRAF mutations, and only 8 percent of those with class 2 BRAF mutations, responded to anti-EGFR treatment regimens. When the researchers evaluated responses based on treatment line, they found that 78 percent of those with class 3 BRAF mutations responded to first- or second-line anti-EGFR treatment compared with 17 percent of patients with class 2 BRAF mutations. No patients with class 2 BRAF mutations responded to anti-EGFR treatment in the third-line setting or later, while 37 percent of patients with class 3 BRAF mutations responded.

“Cancer genomic profiling is rapidly transforming the clinical management of cancer patients,” said the study’s senior author, Hiromichi Ebi, MD, PhD, chief of the Division of Molecular Therapeutics at the Aichi Cancer Center Research Institute in Nagoya, Japan, in an AACR press release. “Results from our study indicate that metastatic colorectal cancer patients with certain BRAF mutations should be considered for anti-EGFR treatment, a new indication for this population of patients.”

Racial disparities in colorectal cancer death rates vary considerably across the United States

A study presented at the Cancer Health Disparities conference in San Francisco last fall investigated the overall and race-specific average annual colorectal cancer mortality rate for the 30 most populous cities in the United States. Using data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics and the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey from 2013 to 2017, the researchers could calculate death rates and determine the number of excess deaths due to racial disparity.

The investigators found that the overall colorectal cancer mortality rate was 14.8 deaths per 100,000 people. While the mortality rates for whites was 14.7 per 100,000, the mortality rate for blacks was 20.9, representing a rate difference of 6.7 per 100,000.

Racial disparities in colorectal cancer mortality rates were observed in 25 cities. Among these cities, the disparity rate difference was the smallest (3.55) in Philadelphia and the largest (13.65) in Washington, D.C.

Presenter and study lead author Abigail Silva, MD, MPH, assistant professor in the Parkinson School of Health Sciences and Public Health at Loyola University Chicago, noted that the rate difference of 6.7 per 100,000 corresponds to 2,252 excess deaths of black Americans from colorectal cancer each year.

“Among the 25 cities with a racial disparity, Seattle and Portland had the fewest excess black deaths, with three each. Chicago fared the worst, with 96 excess black deaths due to colorectal cancer disparities,” Silva said in an AACR press release.

“Local level data are critical for improving cancer outcomes for populations and addressing health inequities,” Silva said. “Each city can use this information to make real, evidence-based changes in policies, services, and funding.”

Looking ahead

The AACR is hosting a Special Conference on Colorectal Cancer in October 2021 to facilitate further discussions and collaboration with the goal of making progress for all patients with this disease. Stay tuned for more information!