Investigational Combination Therapies Improve Responses to Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy research has exploded over the past decade and has led to the approval of seven immune checkpoint inhibitors by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of a multitude of cancers.

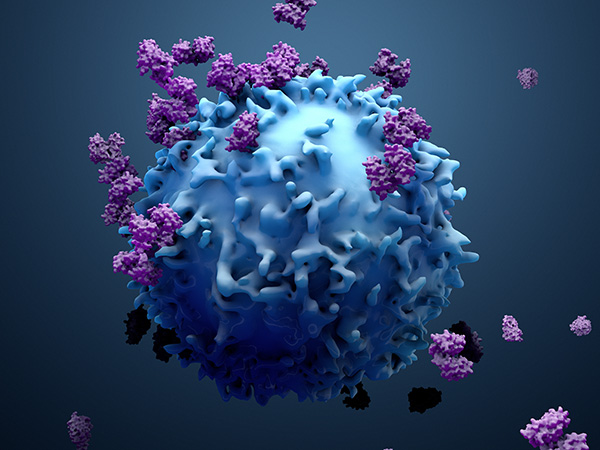

Immune checkpoint inhibitors kill cancer cells by releasing the brakes on the immune system, thereby allowing it to mount an antitumor response. This form of immunotherapy has led to dramatic responses in some patients; however, most patients’ tumors do not respond to immune checkpoint inhibition, and resistance can develop in tumors that initially respond.

One strategy to improve responses is to combine immune checkpoint inhibitors with other therapies. Two studies recently published in Cancer Discovery, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR), examined investigational combination therapies and their impact on responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors.

A mechanism-based approach to overcome resistance in preclinical models

A preclinical study by Antoni Ribas, MD, PhD, professor of medicine, surgery, and molecular and medical pharmacology at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA); director of the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy Center at UCLA; and director of the Tumor Immunology Program at the Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, and colleagues used a mechanism-based approach to understand and overcome resistance to immune checkpoint inhibition in melanoma models. Ribas is President of the AACR.

The researchers focused on mutations of the JAK1, JAK2, and beta-2-microglobulin (B2M) proteins, all of which regulate key immune-activating pathways. JAK1 and JAK2 are involved in the interferon signaling pathway, and B2M is involved in antigen presentation. Loss-of-function mutations in these proteins have been detected in some patients’ tumors that were resistant to immune checkpoint inhibitors, consistent with preclinical studies suggesting that alterations within interferon and antigen-presenting pathways may be involved in resistance.

To better understand the potential roles of JAK1, JAK2, and B2M in resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors, Ribas and colleagues deleted the genes encoding these proteins in several melanoma cell lines. They found that JAK1- and JAK2-deleted cells had reduced interferon signaling, suggesting that mutations in JAK1 or JAK2 might promote resistance by preventing the activation of interferon signaling, an early step in immune activation. In contrast, B2M-deleted melanoma cells retained intact interferon signaling but had decreased levels of MHC class I on the cell surface. Consistent with reduced MHC class I levels, B2M-deleted cells were not recognized by T cells in a co-culture system, suggesting a potential mechanism by which B2M mutations promote resistance to immune checkpoint inhibition.

Using mouse models of melanoma, Ribas and colleagues showed that JAK1-, JAK2-, or B2M-deleted tumors did not respond to single-agent treatment with an immune checkpoint inhibitor that targeted the mouse PD-1 protein. Based on the results from their cell culture experiments, the researchers hypothesized that activating interferon signaling in JAK1- or JAK2-deleted tumors may overcome resistance to the immune checkpoint inhibitor. Consistent with their hypothesis, combining the anti-PD-1 therapy with an agonist of the interferon-activating TLR9 protein led to increased levels of immune-stimulating cytokines, increased tumor infiltration of immune cells, and a significant reduction in tumor growth in mice with JAK1- or JAK2-deleted tumors.

In mice with B2M-deleted tumors, combining the anti-PD-1 therapy with bempegaldesleukin (BEMPEG)—an IL-2 agonist that stimulates immune cells—led to increased immune cell infiltration, reduced tumor volume, and longer survival compared with anti-PD-1 treatment alone. The antitumor effects of BEMPEG were found to be dependent on CD4+ T cells and natural killer cells but not on CD8+ T cells. This finding was consistent with the reduced MHC class I levels on B2M-deleted cells, which precluded recognition by CD8+ T cells.

The authors concluded that disruptions in interferon signaling or antigen presentation could promote resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors and that this understanding could help guide the development of therapies to overcome resistance in patients. Furthermore, they proposed that combining anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibition with agonists of TLR9 and IL-2 could overcome resistance in tumors with mutations in JAK1/2 and B2M, respectively.

BEMPEG and anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibition in patients with solid tumors

In another study recently published in Cancer Discovery, researchers examined a similar combination of BEMPEG and the anti-PD-1 therapy nivolumab (Opdivo), in patients with various solid tumors and found that the combination was well tolerated and led to clinical responses.

The phase I clinical trial enrolled 38 patients with locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors who had not previously received immunotherapy. Of these patients, 11 had melanoma, 22 had renal cell carcinoma, and five had non-small cell lung cancer.

Patients received one of several test doses of BEMPEG, followed by one of two different doses of nivolumab. Objective responses were observed in 22 of 37 (59.5 percent) evaluable patients, and complete responses were observed in eight patients. The median time to response was 1.9 months; the median duration of response was not reached after a median follow-up of 18 months. Of the 24 patients who received the recommended phase II dose, 16 patients (66.7 percent) had an objective response, with a median 67.6 percent tumor reduction. The authors noted that the observed objective response rates were higher than those historically observed with nivolumab monotherapy in prior studies.

In addition, responses were observed regardless of baseline levels of PD-L1 or tumor immune-cell infiltration, suggesting that the combination therapy may also be effective for patients whose tumors would not be expected to respond to nivolumab alone.

The most common treatment-emergent adverse events associated with the combination therapy were flu-like symptoms, rash, fatigue, itchiness, joint pain, decreased appetite, and headache. Eight patients experienced grade 3 or 4 treatment-emergent adverse events. There were no treatment-related deaths.

The results from this phase I trial suggest that combination therapy with BEMPEG and nivolumab may be an effective treatment for patients with solid tumors. Phase II and III clinical trials have been initiated to evaluate the combination in patients with renal cell carcinoma, urothelial cancer, muscle-invasive bladder cancer, and melanoma.

These studies describe just two of the many combination therapies that are being explored to improve responses to immune checkpoint inhibition. The findings underscore the importance of understanding mechanisms of resistance to guide treatment and illustrate how preclinical and clinical studies can contribute to advancing treatment.