Are Prostate Cancers Biologically Different in African American Men and White Men?

In the United States, the rates of prostate cancer diagnosis and mortality have been steadily declining over the past decades, and the five-year relative survival rate is nearly 98 percent. Data for African American men, however, are concerning: Compared with white men, African American men are 1.8 times more likely to be diagnosed with prostate cancer, and 2.2 times more likely to die from the disease.

A substantial portion of the discrepancies in prostate cancer diagnosis and prognosis could be attributed to disparities in socioeconomic factors, including inequalities in wealth, education, and access to health care, many of which are exacerbated by pervasive racism.

But does biology play a role in influencing the clinical outcomes for African American men with prostate cancer? This topic was discussed in several sessions at the AACR’s Virtual Conference on the Science of Cancer Health Disparities in Racial/Ethnic Minorities and the Medically Underserved, held October 2-4. In their presentations, cancer researchers scrutinized complex and diverse biological pathways, including vitamin D receptor (VDR) signaling, metabolic rewiring, and immune signatures, which offered some clues to the alterations that potentially underpin the observed disparities.

The association between vitamin D receptor (VDR) signaling and prostate cancer was established in the 1980s, and subsequently confirmed in several clinical studies. Considering the recent evidence of an increased risk of prostate cancer diagnosis in African American men, Moray Campbell, PhD, from the Ohio State University, examined VDR signaling in normal and tumor cell culture models of African American and European American prostate cancers. His studies showed that VDR has a higher expression, and binds to vitamin D more strongly, in African American prostate cells than in European American prostate cells. Further, VDR signaling response was suppressed in the African American tumor cells, but not in the normal cells. Notably, the gene networks that were repressed in the tumor cells because of VDR signaling suppression include inflammatory and circadian rhythm pathways.

Serum analysis of samples from African American and European American men with high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HGPIN) revealed that 33 percent of the miRNAs associated with the progression of prostate cancer were regulated by VDR signaling in African American men, as opposed to 2 percent in their European American counterparts. Taken together, the studies show that the VDR signaling axis may intersect with the biopsychosocial processes, which may contribute to prostate cancer disparities.

Metabolic reprogramming is a hallmark of cancer, and an individual’s lifestyle can impact metabolic changes. Christy Charles, a research assistant at Baylor College of Medicine, took a metabolomics approach to comparing the landscape of African American and European American prostate cancers. Analysis of approximately 200 metabolites led to the identification of alterations in the metabolites of the methionine cycle in African American prostate cancers. Specifically, the expression of the enzyme adenosine deaminase, which catalyzes the conversion of adenosine to inosine, was found to be elevated. This explains the observed increase in the inosine to adenosine ratio in African American men with prostate cancer, Charles noted. A closer look using cancer cells in culture showed that an increase in the levels of adenosine deaminase decreased the adhesion potential of the cells, which could promote their metastatic dissemination. Following a dissection of the mechanisms activated by adenosine deaminase in decreasing adhesion in cancer cells, Charles identified inhibiting the activity of adenosine deaminase as a potential therapeutic strategy for some African American men with prostate cancer.

A couple of studies examined the immune landscape of African American prostate cancers. Dennis Adeegbe, PhD, from the Moffitt Cancer Center, studied tumor and blood samples from African American men and white men with prostate cancer to compare immune signatures that may impact antitumor responses in the two populations. Tumor analysis revealed no significant differences in the number of lymphoid cells in the two groups of men; however, the CD8-positive T-cell subsets from the African American patients’ tumors displayed a less activated phenotype, accompanied by upregulation of the immune checkpoint proteins CTLA-4 and PD-1. Analysis of serum samples showed downregulation of cytokines and chemokines that regulate immune-cell function and recruitment in African American patients. Together, these results suggest that the prostate cancers of African American men harbor immunological signatures that impede antitumor responses and help evade immune attack, all of which facilitate tumor aggressiveness and progression.

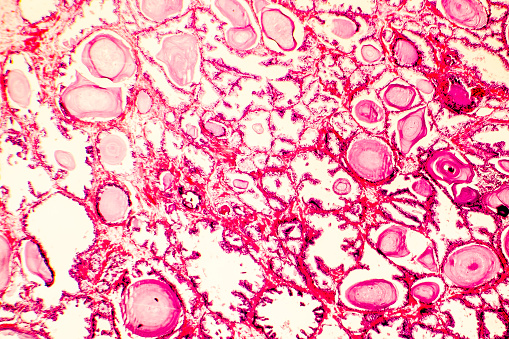

Tamara Lotan, MD, from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, analyzed prostatectomy tissues from 200 African American men and grade- and stage-matched 200 white men by performing protein, genomic, and epigenomic profiling on tumor microarrays. While no differences were observed in the relative abundance of T-cell subtypes, tumors from African American and white men were found to have distinct molecular landscapes, and the immune microenvironment varied by race and by molecular subtypes.

Reducing disparities along the prostate cancer continuum

Timothy R. Rebbeck, PhD, professor of cancer prevention and epidemiology at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and professor of medical oncology at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, delivered a lecture titled “Biological and social influences on disparities in prostate cancer mortality.” Rebbeck highlighted the disparities that exist through the continuum of prostate cancer progression, starting from HGPIN through prevalent cancers (cases that were not diagnosed but detected during autopsy), incident cancer, and prostate cancer mortality. “Blacks have higher rates of these traits at every phase along the prostate cancer continuum,” he noted, referring to the biological and social factors that influence the disparities at every stage of the disease. Rebbeck reviewed the disparities in access to care and prostate cancer screening, differences in the immunological pathways, the different effects some genetic variations associated with prostate cancer may have on prostate cancer risk in Black men versus white men, and disparities in the receipt of treatment.

“Because of this complexity, because different factors are working at different time points during the cancer continuum to result in a disparity, we have to think about how we can tailor interventions to these complex, time-sensitive, and context-sensitive influences,” Rebbeck said.