How Two Nobel Prize-winning Discoveries Help Shape Liver Cancer Prevention

Unlike cancer incidence rates overall, which are decreasing in the United States, the incidence rate of liver cancer has been increasing in recent decades.

While there are a host of risk factors that contribute to liver cancer risk—including heavy alcohol use, cigarette smoking, and obesity—the leading cause of liver cancer is infection with the hepatitis B virus (HBV) or the hepatitis C virus (HCV). In fact, it is estimated that at least 80 percent of global hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cases, the most common type of liver cancer, are caused by chronic infection with HBV or HCV.

These two types of viruses, which are transmitted through the blood, are especially problematic because infected individuals often do not have symptoms until serious complications arise. The liver, which is under constant attack from the virus, can become fibrotic over time as healthy cells are replaced by scar tissue. These changes to the liver can reduce its function and can ultimately lead to the development of liver cancer.

The discovery of hepatitis viruses didn’t occur until the second half of the 20th century. In the 1960s, while analyzing blood samples from different populations across the world, Baruch Blumberg, MD, PhD, identified the surface antigen of HBV. Blumberg and others found that this antigen was present in those with hepatitis, and that HBV could cause liver cancer. Blumberg received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1976 for his work on HBV.

The discovery of HCV would follow in later years. Harvey Alter, MD, and colleagues demonstrated in the 1970s that many cases of transfusion-related hepatitis were not related to hepatitis A or B, yet the blood transferred from these patients could cause hepatitis in chimpanzees, indicating the presence of an unknown pathogen. Later studies demonstrated that this pathogen had viral characteristics, and the subsequent disease associated with this virus was known as “non-A, non-B” hepatitis. Michael Houghton, PhD, and others isolated the genetic sequence of the virus, which was named HCV. Finally, Charles Rice, PhD, and colleagues proved that HCV could cause hepatitis. These three scientists received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine this year for their discovery of HCV.

The work of Blumberg and others led to vaccinations for hepatitis B, which are now administered in the United States as routine preventive care. Despite vaccination efforts, it was estimated that over 250 million people worldwide were infected with HBV in 2015. As discussed last year during AACR Annual Meeting 2019, HBV is not currently curable, yet lifetime administration of antiviral treatment can suppress viral infection and reduce liver cancer incidence. Infection with HBV is the leading cause of HCC incidence in Asia and Africa.

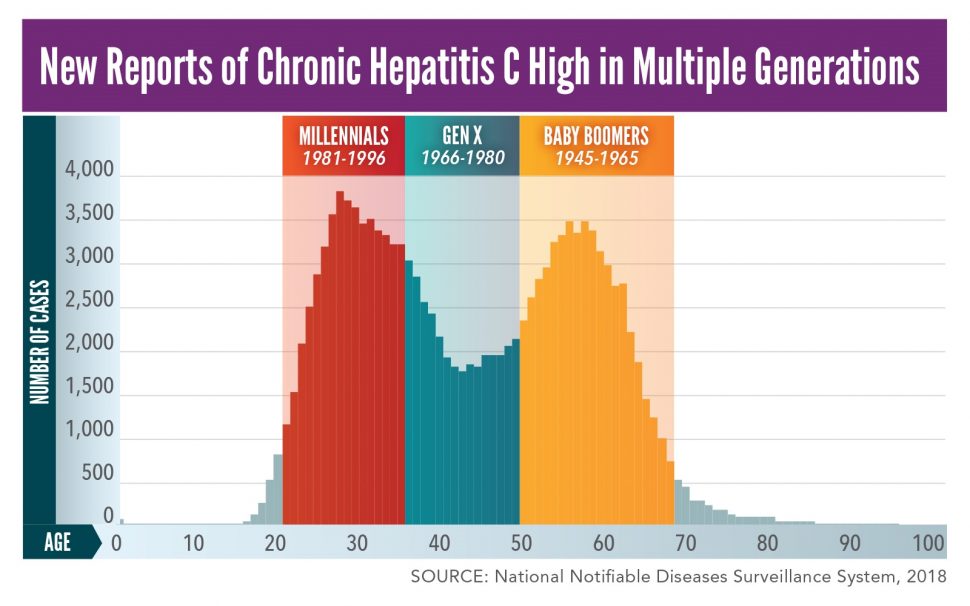

While there is not yet a vaccine for hepatitis C, there are many effective treatments for HCV infection, which can reduce the incidence of HCC. However, because most people with an HCV infection do not have symptoms, many are not getting tested for the virus. As a result, hepatitis C is increasing rapidly in the United States—between 2009 and 2018, the annual rate of reported acute hepatitis C tripled, and young adults (those ages 20-39) had the highest rate of new hepatitis C cases in this time frame. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) now recommends a one-time screening of all adults 18 years and older for infection with HCV. Additionally, the CDC recommends that pregnant women during every pregnancy and those with ongoing risk factors (including those who currently inject drugs and share drug preparation equipment) be tested for infection with HCV. Infection with HCV is the leading cause of HCC incidence in North America, Europe, and Japan.

October is Liver Cancer Awareness Month. While there is no standard screening test for liver cancer, preventive measures—such as abstaining from heavy alcohol use and cigarette smoking, maintaining a healthy weight, getting screened for infection with HCV, and immunization for hepatitis B—can reduce the risk of developing liver cancer.