Experts Forecast Cancer Research and Treatment Advances in 2021

2020 was filled with unexpected challenges for cancer research and patient care. As many of us shifted our lives online in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, cancer research was paused, clinical trials were put on hold, appointments were rescheduled, and conferences were canceled or reformatted.

All this occurred amidst a global pandemic that has killed more than 1.9 million people worldwide, a plummeting economy with record unemployment levels, and a national reckoning with racism and racial disparities in all facets of society—including health care.

But there was also progress.

An unprecedented level of scientific collaboration and dissemination led to rapid research advances, culminating in the authorization of two vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 less than 12 months after the first reported COVID-19 cases. Twenty-one novel oncology drugs were approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2020, including for difficult-to-treat cancers such as triple-negative breast cancer and certain gastrointestinal stromal tumors. The first liquid biopsy next-generation sequencing tests were approved, the first-in-human trial of off-the-shelf CAR T-cell therapy was launched, and the first comprehensive report on cancer disparities was released by the AACR.

With 2020 behind us, what might we expect from 2021?

Each year, we publish predictions from prominent cancer researchers summarizing the key advances in cancer research and treatment we can expect to see in the new year.

This year, we spoke with thought leaders on five timely subjects, including COVID-19, cancer disparities, cancer prevention, immunotherapy, and precision medicine. These researchers provided their thoughts on the greatest challenges and expectations for their respective fields in the upcoming year.

COVID-19 and Cancer

As we begin the new year, it is apparent that the COVID-19 pandemic will continue to affect cancer research and patient care for the foreseeable future.

President of the AACR and Chair of the AACR COVID-19 and Cancer Task Force, Antoni Ribas, MD, PhD, FAACR, discussed the challenges that the cancer field will continue to face as the pandemic persists into 2021, as well as his perspectives on where the field is headed.

Vaccinating patients with cancer

One of the major accomplishments to expect in 2021 is widespread COVID-19 vaccination, which Ribas hopes will be a turning point for patients with cancer. “The pandemic has delayed cancer diagnoses, has limited access to care and lifesaving treatments, and has unevenly impacted already vulnerable populations,” said Ribas, professor of Medicine, Surgery, and Molecular and Medical Pharmacology at Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of California, Los Angeles. “Moving forward, I hope that vaccination will allow us to return to the care that has saved so many lives from the pandemic of cancer, which includes early detection and access to effective treatments.”

Due to the disproportionate risks that COVID-19 poses for patients with cancer, Ribas and the AACR COVID-19 and Cancer Task Force advocated for patients with cancer to be given priority vaccination in a recent article for the AACR journal Cancer Discovery.

Ribas expects that 2021 will also provide additional information about the effects of cancer on COVID-19 vaccination. An important question is whether cancer therapies that either suppress or boost the immune system will alter the efficacy of vaccination, Ribas explained. “The limited evidence we have does not suggest that cancer or cancer treatments have an effect on COVID-19 vaccines, but we need to complete additional trials in patients undergoing various therapies to determine their impact, if any, on the ability to mount a protective response to COVID-19.”

Adapting cancer clinical trials

“The pandemic has led to the biggest change to clinical trials in the last 30 to 40 years,” said Ribas. He predicts that many of the changes will continue into 2021 and beyond due to the positive impacts they will likely have on increasing access to clinical trials in the future.

Prior to the pandemic, clinical trials required numerous in-person visits, not only for receiving treatment, but also for completing paperwork and undergoing routine imaging and blood draws, Ribas explained. However, as medical facilities began to scale back operations last spring, clinical trials were quickly adapted to allow participants to continue their involvement without having to visit the clinic. Patients were able to provide consent remotely, utilize telemedicine for appointments, and receive oral medications and other treatments at home. For procedures that required in-person visits, such as imaging or blood tests, patients were able to visit local facilities rather than having to travel to distant research facilities.

“The pandemic is going to have lasting impacts on cancer research. One benefit of the pandemic is that it has forced clinical researchers to determine which procedures are absolutely necessary to do in person and which can be completed remotely,” Ribas noted. Although he acknowledged that there has been reduced clinical trial enrollment during the COVID-19 pandemic, he expects that in the long run, “these changes will broaden the ability of people to participate in clinical trials, especially for patients who do not live near research centers and may otherwise not have the means to travel for multiple visits.”

Supporting the cancer research workforce

An important goal identified by Ribas for the upcoming year is supporting cancer research through the challenges brought on by the pandemic.

“As the pandemic began, many of the activities that were considered the norm in cancer research had to be changed,” Ribas said, citing the cancellations or adaptations of scientific conferences as one key example. “The first large virtual conference in the field was the AACR Virtual Annual Meeting, which had to be organized within just a month without any road map for this type of meeting.” Twenty-five smaller conferences organized by the AACR were also converted to virtual meetings in 2020.

“It was a big change for the organization and the broader scientific community, but it also provided an opportunity to embrace new technologies to reach more people and make the latest cancer research content available to people around the world,” Ribas noted.

Looking ahead to 2021, Ribas anticipates that most conferences will remain virtual. “Once we reach the tipping point where enough people have been vaccinated to effectively prevent viral spread, we can start thinking about a timeline to resume in-person conferences where there are more opportunities for researchers to interact and collaborate, but there are going to be a lot of logistical factors to consider.”

Ribas expects that the pandemic will continue to be particularly challenging for early-career investigators who are facing a lack of funding and job opportunities in the next year due to budgeting shortfalls at foundations, universities, and research institutions. Other pandemic-related challenges include reduced time in the lab to generate data and the inability to travel to job interviews or establish connections at in-person conferences.

In light of these challenges, Ribas believes supporting early-career investigators should be a priority in 2021. He noted that the AACR COVID-19 and Cancer Task Force is examining ways to address these challenges, such as advocating to lawmakers to increase funding for cancer research. “There are a lot of things we need to act on in a short time,” he said.

Ribas added that cancer research has not only helped improve treatments for cancer, but has also greatly benefited other research disciplines, including treatment and vaccine development for COVID-19. “The vaccines from Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna were both developed using a platform that was initially conceived for cancer immunotherapy,” Ribas explained. “Because of cancer research, this technology was readily available to adapt for COVID-19 vaccination. It took only a month and a half from the time the virus was sequenced before the first patients were receiving COVID-19 vaccines in clinical trials.” Advances in cancer therapeutics have also benefited the treatment of COVID-19, as some of the drugs used in cancer treatment have shown to be effective for patients with COVID-19.

“If we don’t step in and support cancer research through this time, there will be long-lasting consequences for the medical field at large,” he noted.

Ribas is optimistic that the incoming presidential administration will be supportive in addressing the hurdles the cancer research community now faces. “In President-elect Biden and Vice President-elect Harris, we have two longstanding advocates of using science to make public policy and funding decisions,” he said, adding that both Biden and Harris have lost family members to cancer. “We’ve been set back so much by this pandemic, but I expect the new administration will partner with the cancer research community in alleviating some of the major problems that the field is facing now.”

Cancer Disparities

2020 brought us a new pandemic, but it also forced us to reckon with a very old plague—that of racial inequity.

“Several cataclysmic events occurred over this past summer—the horrific murders of African Americans at the hands of law enforcement officers and the COVID-19 pandemic with its disproportionate impact on minorities—all forcing us to confront systemic racism and its effects on public health,” said surgeon and breast cancer researcher Lisa Newman, MD, MPH, chief of Breast Surgery at New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Newman is a member of the AACR Minorities in Cancer Research Council.

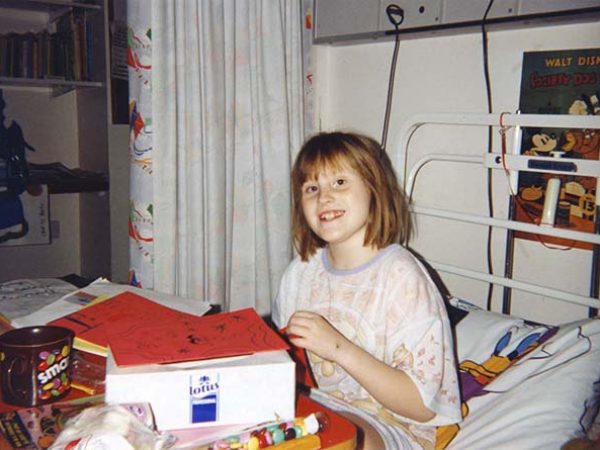

Disparities in health are seen in cancer as well, with minority populations, including African Americans, having higher incidence and mortality rates for many cancer types. Minorities are also more likely to be diagnosed with advanced and aggressive cancers and are underrepresented in clinical trials for cancer treatments.

The biological and social factors that contribute to disparities in cancer incidence and mortality are under investigation. Newman discussed her predictions for where the cancer disparities field is headed in 2021.

Identifying ancestral determinants of cancer risk

Newman anticipates that one of the major focuses of the cancer disparities field in the next year will be studying how genetic ancestry impacts cancer incidence and treatment outcomes. Prior work has shown that Western sub-Saharan ancestry increases the risk of triple-negative breast cancer. This may account for the greater rates of this breast cancer subtype among African Americans, many of whom have Western sub-Saharan ancestry due to the colonial-era trans-Atlantic slave trade. Similarly, Indigenous American ancestry in Latina women has been shown to be associated with increased risk of HER2-positive breast cancer. According to Newman, identifying potentially actionable genetic determinants of ancestry-related breast cancer risk will be one key research direction in 2021. She noted that clinical trials are already underway to evaluate the utility of germline markers, including markers of ancestry, in personalized screening programs for breast cancer.

“We are only beginning to appreciate the value of germline genetics in evaluating ancestry and the role that it plays in cancer risk,” said Newman. “I think we will be seeing a lot of similar research for other cancer types. This is a very exciting direction in cancer disparities research.”

Determining the impact of allostatic load

Newman also expects that the field will continue to study how allostatic load—the “wear and tear” on the body from stress—impacts cancer risk. “We’re learning that cumulative stresses, such as exposure to racism and discrimination over a lifetime, can lead to epigenetic changes that may then affect risk for a variety of cancers,” Newman said. Epigenetic changes can increase cancer risk through effects on the microbiome, among other mechanisms, she added.

Newman explained that the higher rates of certain cancers in minority populations may be due, in part, to the biological changes that occur in response to the unique stresses they disproportionately face, such as racism and poverty. She anticipates that advances in 2021 will provide a deeper understanding of the biological consequences of stress in minority populations.

Understanding social determinants of cancer disparities

Another priority for the field in 2021 will be expanding knowledge about the social determinants of health and how they impact cancer risk, according to Newman. “We are just starting to scratch the surface in understanding how social determinants of health influence disparities in cancer risk and outcomes,” she said.

Factors such as poverty and lack of health care access among minority populations can promote obesity and other comorbidities that increase cancer risk. As an example, the higher poverty rate among African Americans is associated with a higher proportion of African Americans living in food deserts with lower access to healthy dietary options, Newman explained.

Newman anticipates that the COVID-19 pandemic and recession will exacerbate many existing cancer disparities due to the greater losses of jobs and health insurance experienced by minority populations. Furthermore, the hiatus in screening programs at the onset of the pandemic will likely lead to later diagnoses of cancer in communities that already suffer from more advanced stage distribution. “Minority populations with impaired access to screening programs are going to suffer disproportionately,” Newman said.

She also cited the overwhelming impacts of the pandemic on safety-net hospitals, which are mostly found near minority communities and provide the majority of care for patients who lack health insurance. Newman explained that safety-net hospitals have more limited financial margins that have been devastated by the pandemic because of the high costs of critical care associated with COVID-19. “When safety-net hospitals try to return to somewhat normal practices after the pandemic, they are going to be much more behind financially in trying to provide cancer care and appropriate screening. This will end up disproportionately impacting minority populations,” Newman noted.

Nevertheless, Newman is encouraged by the greater social awareness of racial inequities among the general public. “I think the American society has been awakened to the depths and tragedies of systemic racism and disparities in public health this year,” she said. “I hope this awareness will result in the expansion of much-needed research and investment in health equity initiatives to improve outcomes for communities that are socioeconomically disadvantaged.”

Cancer Prevention and Early Detection

While much of cancer research is focused on developing treatments for advanced cancers, a subset of the field aims to understand how to prevent cancer from occurring at all, as well as how to detect cancer earlier, when it is more easily treated.

“The payoffs of cancer prevention are huge,” said Raymond DuBois, MD, PhD, FAACR, who is Chair and President of the AACR Foundation and a Past President of the AACR. “I’m optimistic that we will see increased understanding and enthusiasm for this area of cancer research as we continue to learn more.”

DuBois, also a professor and Dean of the College of Medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina and a member of the National Academy of Medicine, discussed his predictions for the cancer prevention field in 2021.

The PreCancer Atlas: Characterizing premalignant changes

What changes occur as normal tissue transitions to cancer?

Can the changes found in premalignant tissues be targeted to prevent cancer from forming?

To answer these questions, research groups from around the world have been working to generate a PreCancer Atlas with information about mutations and other early changes that occur at the molecular and cellular levels before and during cancer development. DuBois expects this to remain a major focus of the cancer prevention field in 2021 and a key long-term strategy for intercepting cancers at an early stage.

“Characterizing premalignant changes will provide insight into the novel targets that may be present in this early phase of cancer development, as well as the pathways that are operative in the evolution to cancer,” he explained. “Understanding these changes will provide crucial information for developing new therapeutic approaches.”

DuBois is particularly excited about the emerging evidence of changes in the type and density of immune cells in the premalignant microenvironment, which cause the premalignant lesions to become more resistant to the immune system. “I was surprised to learn that this immunosuppressive environment was established so early,” said DuBois, adding that this new information provides an opportunity to explore using vaccines or other interventions to inhibit immunosuppressive cells at an early stage to induce regression of premalignancies.

“This story is still unfolding,” he said. “[This] year is going to be very exciting as publications come out showing the changes that are present in the premalignant tissue microenvironment, the potential vulnerabilities that exist in immune cells, and how we might target them in a nontoxic way to have a big impact.”

Development of biomarkers and diagnostic tests

Another area that DuBois expects the field to focus on in 2021 is the development and validation of biomarkers that would allow researchers to easily detect and monitor premalignant conditions. “It currently takes several months to years to conduct clinical trials examining disease progression and outcomes in patients with premalignant conditions,” said DuBois. “If we had validated biomarkers from premalignant lesions that could reliably indicate how patients were responding to clinical interventions, we could shorten the time and cost needed to conduct those trials.” He noted that this approach has been successful in cardiovascular disease research, where high levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol serve as a biomarker for cardiovascular disease risk, allowing researchers to study the impact of investigational drugs on disease risk with a simple blood test. DuBois expects that findings from the PreCancer Atlas and other efforts will be key to identifying useful biomarkers for premalignancies.

In addition, DuBois highlighted the need for accurate diagnostic tests to assess the risk of disease progression in individuals with premalignancies. “If we had a blood test that could distinguish between patients who were likely to develop a malignant cancer and those likely to develop a benign tumor, we could intervene early and appropriately for each population,” he explained. “We could limit the use of the more aggressive treatments to patients with a greater risk of malignant cancer and avoid those detrimental side effects in patients with lower risk.”

Encouraging healthy behaviors and cancer screenings in the age of COVID-19

A key element for cancer prevention is encouraging individuals to adopt healthy behaviors and undergo routine screenings. “It is estimated that 40 to 50 percent of cancers could be prevented if we could get everybody to follow all of the current recommendations for screening and healthy lifestyle behaviors,” said DuBois. “If we could do that successfully, it would be one of the biggest advances of our lifetime.”

To reach this goal, understanding the reasons underlying unhealthy lifestyles will be critical. Many cancer-causing behaviors, such as smoking and poor diet, are rooted in addiction, so investing in behavioral and addiction science will be important to curbing these behaviors, DuBois explained. “We need to better understand the pathways in the brain that cause these addictions so that we can find more effective ways to intervene that are durable.”

Identifying and addressing the obstacles to cancer screening will also be important. In 2021, a major hurdle will be the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, which has already led to a dramatic decline in screening rates.

“During the early stages of the pandemic, the last thing anyone wanted to do was go to a clinic and risk exposure, so people started putting off routine screenings,” said DuBois. “Now that we’ve realized that we’re going to be living with this virus for some time, we are trying to encourage patients to resume screenings.” Despite this encouragement, screening rates are still far below pre-pandemic levels. “That’s a huge problem, as it means many cancers may not be detected until it’s too late,” DuBois noted. Consistent with these concerns, an editorial by National Cancer Institute Director Ned Sharpless, MD, predicted that there may be 10,000 additional deaths from breast and colorectal cancers over the next decade due to delays in screening caused by the pandemic.

For patients who may be apprehensive about scheduling in-person appointments, DuBois recommends calling the clinic ahead of time to inquire about the safety precautions in place. “In my experience, many health care facilities have clearly defined procedures to help mitigate spread, such as social distancing, requiring masks, and decreasing the density in waiting rooms,” he explained. “Hearing about these has alleviated patient concerns to some degree, but I think this is going to continue to be a challenge until a vaccine is distributed widely.”

Immunotherapy

“Due to the pandemic, there is a much greater appreciation of the immune system among the general public,” said Marcela Maus, MD, PhD, director of the Cellular Immunology Program at Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center and associate professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School “I’m hoping this understanding and the successful elimination of COVID-19 through vaccination will restore optimism and reverence for science and the immune system on a massive scale.”

Perhaps best known for its role in combatting viral and bacterial pathogens, the immune system is also able to respond to cancer cells, a function that has been utilized to treat patients with cancer. This class of cancer therapy—known as immunotherapy—encompasses several forms of treatment, all of which use a patient’s own immune system to target and eradicate their cancer. Immunotherapy has led to durable responses in many patients and has revolutionized cancer treatment over the last decade.

“While vaccination for COVID-19 will be the major immunology achievement of 2021, I expect that immunotherapy will continue to drive increased responses and cures in patients with cancer as well,” Maus noted.

Despite its many successes, immunotherapy does not benefit most patients and can be associated with resistance and severe side effects. Furthermore, the engineering of immune cells for certain forms of treatment requires time that many patients do not have. Maus discussed some of these challenges and the advances she expects to see in this field in 2021.

New combinations for immune checkpoint inhibition

Immune checkpoint inhibitors help release the brakes on the immune system, allowing it to mount an antitumor response. This form of immunotherapy has led to dramatic and durable responses in some patients; however, the majority of tumors do not respond to this treatment, and many of the tumors that initially respond eventually develop resistance.

One strategy to improve the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors is to combine them with other therapies. Maus expects to see new combination therapies emerge in 2021. “I think new combinations of immune checkpoint blockade with chemotherapy and immune agonists will continue to make inroads in the fight against solid tumors,” she said.

Advances and challenges for adoptive cell therapy

Adoptive cell therapy (ACT) is a class of immunotherapy in which a patient’s T cells are extracted, engineered, multiplied, and reintroduced into the patient. ACT is effective for some hematologic malignancies, but it has not been successful for solid tumors. Maus anticipates that there will be advances in ACT for both hematologic malignancies and solid tumors in 2021.

“In hematologic malignancies, I expect engineered T cells to be adopted more widely for patients with lymphoma, and perhaps move up a line or two of therapy,” she explained, adding that treating patients with ACT earlier would lower their exposure to chemotherapy and its long-term toxicities. Maus also predicts that new forms of engineered T cells could potentially become available, including idecabtagene vicleucel (ide-cel) and ciltacabtagene autoleucel (cilta-cel) for the treatment of multiple myeloma.

As far as solid tumors, Maus anticipates that publications in 2021 will demonstrate some efficacy for new therapies in development for solid tumors, but she expects that toxicity will likely be observed before durable responses. “I think any therapy that mediates antitumor responses in solid tumors will have some toxicity, but I think those side effects will be mitigated by medical interventions,” she said. Maus suggested that improving ACT for solid tumors may require combining it with other therapies or adding regulatory mechanisms to the engineered immune cells so that the response can be controlled to limit toxicity.

A challenge that Maus believes the field needs to address in 2021 and beyond is expanding access to CAR T-cell therapy, a type of ACT. “Even though CAR T cells have achieved unprecedented efficacy in patients with lymphoma, they are still relatively underutilized due to the high cost, the high level of care and bespoke manufacturing required, and issues with health care infrastructure and payment models,” she explained.

“Something here has to change,” Maus added. “All of the relevant stakeholders need to find a way to deliver on the promise of potentially curative cancer treatments for all patients.”

Understanding mechanisms of resistance to immunotherapy

Maus also predicts that the advent of new preclinical models in 2021 will bring about a greater understanding of the cellular pathways underlying resistance to immunotherapy. She explained that to date, most preclinical models of resistance have examined the role of just one cell type at a time; however, she expects to see the emergence of more comprehensive models in 2021 that will allow researchers to explore how different immune cells interact with each other and with the tumor. Additionally, Maus expects that single-cell technologies, such as transcriptional profiling, will enable researchers to better define the contributions of all immune cells, including the patient’s normal, non-engineered immune cells. These advances will also allow researchers to determine the impact of various interventions on immune function and immunotherapy resistance, Maus noted.

“There has been a lot of focus on identifying mechanisms of resistance to CAR T-cell therapy and to immune checkpoint inhibition,” she said. “I’m optimistic that these will start to coalesce and lead to rational drug combinations to target resistance pathways and restore immune-mediated elimination of cancer.”

Precision Medicine

In its simplest definition, precision medicine aims to use a tumor’s molecular features to guide treatment, explained Keith Flaherty, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Editor-in-chief of the AACR journal Clinical Cancer Research.

He noted that while basic precision medicine principles have been employed for some time, such as the traditional classification of breast cancer subtypes, the goal of truly precise and personalized cancer treatment has yet to be achieved. However, Flaherty is optimistic that the utilization of next-generation sequencing and large-scale data mining will bring the field significantly closer to this goal—particularly in the immunotherapy realm.

More precise deployment of PD-1/PD-L1-targeted therapeutics

While inhibitors of the PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint have led to dramatic responses in many cancer types, only a small portion of patients experience a substantial benefit from these therapies. Identifying the molecular features beyond PD-L1 expression that determine which tumors are sensitive to these therapies—and using them to stratify patients for treatment—will be the primary direction of the precision medicine field in 2021, Flaherty predicted.

“Looking ahead to 2021, I’d say the use of biomarkers for PD-1/PD-L1-targeted therapies is going to finally bring us into the era of precision medicine,” said Flaherty, noting that most other precision medicine strategies are in earlier stages of investigation. “I expect that we are going to see the adoption of positive selection biomarkers and—for the first time—the use of negative selection biomarkers in clinical trials to triage patients between different immunotherapy strategies,” he added.

The use of liquid biopsy and circulating tumor DNA to detect and monitor such biomarkers has the potential to provide added depth and convenience compared to current methods; however, Flaherty expects that it will be some time before this approach is widely used. “Eventually, these technologies will begin to give us the information we need to analyze retrospective outcomes and identify whose tumors respond,” he explained.

In addition to allowing more precise deployment of existing immune checkpoint inhibitors, Flaherty expects that understanding the molecular features that predict how tumors respond will facilitate the development of next-generation immunotherapies. “Once you understand which tumors are less likely to respond to PD-1/PD-L1-directed antibodies, you can then focus your efforts on developing new immunotherapies specifically for these types of tumors, thereby benefiting patient populations that do not respond to the current options.”

Targeting fusion oncogenes

The development of therapies to target fusion oncogenes is another direction that Flaherty expects the precision medicine field to explore in 2021 and beyond. “We have an increasing appreciation that tumors driven by fusion oncogenes are genetically simple,” he said. “If you can effectively target the fusion oncogene, you can achieve deep and durable clinical benefit.”

A classic example of this approach is BCR-ABL targeting for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. In recent years, therapies targeting NTRK or RET fusions have also been approved for the treatment of various cancers. Other fusion oncogenes that are emerging as potential therapeutic targets include FGFR fusions and BRAF fusions, according to Flaherty.

“It’s becoming increasingly clear that fusion oncogenes may be the best type of mutation to target—better than point mutations—to achieve high response rates,” he added. “There will be some more successes in 2021, but in the next few years, we can probably expect to see a saturation of this area.”

Targeting DNA damage response proteins

Flaherty predicts that developing inhibitors that target proteins within the DNA damage response (DDR) will be another research direction in the upcoming years. “DNA repair proteins such as ATM, ATR, Chk1, and DNA polymerase-β are all subject to genetic alterations in cancer, providing potential therapeutic targets,” he explained.

Flaherty noted that an extensive set of molecular features may define how a tumor responds to inhibitors of these proteins, similar to what has been observed for inhibitors of the DDR protein PARP. While PARP inhibitors are most effective in ovarian and breast cancers that have BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations, they also show efficacy in cancers with other DNA repair deficiencies, as well as in some cancers with no apparent DDR deficiencies at all. Based on emerging clinical evidence, Flaherty expects similar observations to be seen with inhibitors of other DDR proteins. Identifying the molecular features that connote sensitivity to these drugs will be another major research focus of 2021 and beyond, Flaherty predicted.

“We’re beginning to connect the dots between preclinical data about the molecular features found in tumors and their association with clinical responses to drugs targeting the DDR pathway,” said Flaherty. “In 2021, I think we will see mounting evidence that this class of drugs should become a part of standard therapy, admittedly with further research needed over the next few years.”