Recent AACR Conference Evaluates the Effects of Aging and Obesity on the Tumor Microenvironment

The first AACR virtual meeting of 2021, held Jan. 11-12, focused on the tumor microenvironment, the complex framework of immune cells, blood vessels, fibroblasts, and other cell types that surround a tumor and can affect disease progression or response to treatment. This special conference, titled The Evolving Tumor Microenvironment in Cancer Progression: Mechanisms and Emerging Therapeutic Opportunities, drew nearly 350 virtual attendees and featured eight plenary sessions spanning diverse topics in the field.

One of these plenary sessions, “Systemic drivers of progression: from aging to obesity,” focused on how modulation of the tumor microenvironment by aging and obesity could potentially be exploited to treat cancer. Speakers in this session included Marco Demaria, PhD, from the European Research Institute for the Biology of Aging (ERIBA) in Groningen, Netherlands; Ashani Weeraratna, PhD, from Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore; and Daniela Quail, PhD, from McGill University in Montreal. The final keynote of the meeting, delivered by Judith Campisi, PhD, from the Buck Institute for Research on Aging in Novato, California, gave an overview of senescence, a dynamic process associated with aging and cancer.

Senescence: an evolutionary balancing act

Cancer, Campisi began, is largely a disease of aging, as the vast majority of cancers are diagnosed in individuals over the age of 50. “We are actually remarkably protected against cancer,” she said, noting how tumor suppressors help to delay the onset of cancer until later in life.

Campisi explained that tumor suppressors fall into one of two categories: caretakers or gatekeepers. While caretakers help to safeguard the genome by preventing or repairing DNA damage, gatekeepers eliminate or arrest damaged cells, either through apoptosis or senescence.

Senescence is a state of cell cycle arrest. While senescent cells have stopped dividing, they remain metabolically active and can influence their surrounding microenvironment through a multifaceted secretory phenotype, or SASP (for senescence-associated secretory phenotype). The SASP is dynamic and can change over time, said Campisi, resulting in both immunosuppressive and proinflammatory effects.

Senescence is tied to a host of processes, including wound healing, embryonic development, and most notably, aging. Senescence is also linked to both tumor suppression and metastasis, making it “an evolutionary balancing act,” Campisi said.

Senescence in anticancer treatments

Senescent cells accumulate as we age and seem to promote either the onset or the progression of many different chronic diseases, Demaria explained. However, “senescence is still a very important tumor suppressive mechanism because of the stability of the cell-cycle arrest,” he said.

Because senescent cells cannot multiply, senescence is a desired outcome of many anticancer therapies, said Demaria. Indeed, many cancer therapeutics can induce senescence in malignant cells, he said. However, because many of these therapies are given systemically, this can cause premature senescence in tissues unaffected by cancer, which could lead to secondary pathologies and side effects.

Demaria reviewed results from his study published in the AACR journal Cancer Discovery, which illustrated that premature senescence, as induced by chemotherapy in cancer-free mice, resulted in a variety of pathologies, including physical dysfunctions, cardiomyopathy, myelosuppression, and inflammation. The study also revealed that mice with cancer treated with chemotherapy followed by treatment with a senolytic drug—which eliminated the senescent cells—experienced reduced metastasis and tumor relapse compared with mice treated with chemotherapy alone. While this so-called “two punch” approach could reduce the detrimental effects of therapy-induced senescent cells, Demaria wondered if any pre-existing drugs could generate a type of senescence that is better tolerated.

His research group turned to cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors, such as abemaciclib (Verzenio) and palbociclib (Ibrance), which are approved treatments for certain patients with breast cancer. They found that treatment with either abemaciclib or the chemotherapeutic doxorubicin induced cellular senescence in healthy mice—however, the SASP associated with these two treatments were markedly different. Notably, the SASP in abemaciclib-treated animals lacked pro-inflammatory factors associated with the NF-κB signaling cascade. Further studies revealed that abemaciclib treatment was less toxic than doxorubicin treatment in healthy mice, and while doxorubicin-induced senescence fostered tumor growth in mice implanted with breast cancer cells, abemaciclib-induced senescence did not.

“While different cancer treatments, such as CDK4/6 inhibitors or standard chemotherapy, can induce premature senescence in mice, the type of senescence is very different,” Demaria said. He noted that anticancer interventions with CDK4/6 inhibitors may result in better outcomes for those at increased risk for frailty and disease, including populations of advanced age.

Aging and lipid metabolism in melanoma

Weeraratna began her presentation by noting that the human population is rapidly aging, and that nearly a quarter of the global population will be over the age of 60 by the year 2050. This observation, coupled with the fact that older individuals are more susceptible to cancer, will culminate in a significant public health burden in the coming years, she said.

The Weeraratna laboratory is particularly interested in melanoma, a disease in which older patients tend to have poorer prognoses compared with younger patients. She reviewed a study, recently published in Cancer Discovery, which investigated how changes in lipid metabolism in the aged microenvironment can affect responses to targeted therapy in the context of melanoma.

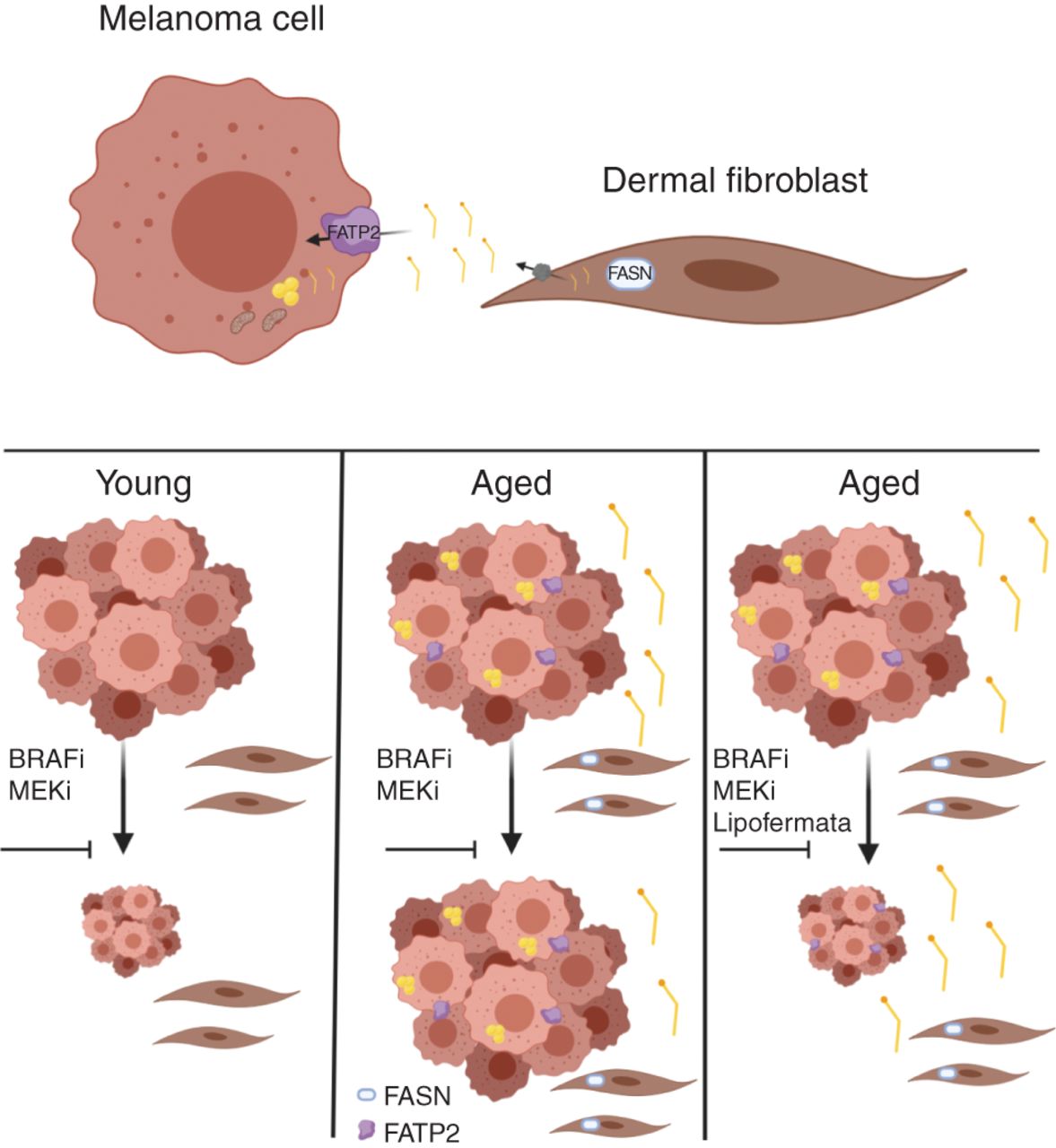

Fibroblasts are key players in the tumor microenvironment, and as fibroblasts age, they can affect the behavior of melanoma cells, Weeraratna said. In her study, Weeraratna and colleagues demonstrated that aged fibroblasts have increased expression of fatty acid synthase (FASN) compared with young fibroblasts, and that melanoma cells grown in conditioned media from aged fibroblasts accumulated more lipids compared with melanoma cells grown in conditioned media from young fibroblasts. Further analyses revealed that the fatty acid transporter protein FATP2 was responsible for this lipid accumulation, and that the expression of FATP2 was elevated in patients with melanoma over the age of 50.

Weeraratna and colleagues then analyzed how targeting FATP2 (either pharmacologically or through genetic knockdown) affected melanoma growth in mice treated with BRAF and MEK inhibitors. While FATP2 did not affect melanoma growth in young mice, targeting FATP2 in aged mice sensitized the animals to targeted therapy and increased their survival, suggesting a potential therapeutic approach for older patients with melanoma.

“It’s really important that we consider the aging microenvironment when treating patients and designing preclinical studies,” Weeraratna concluded.

Obesity and breast cancer metastasis

While aging may be inevitable, the same is not true for obesity. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), however, the prevalence of obesity was estimated to be over 40 percent between 2017 and 2018 in the United States. As described in detail in this previous post, obesity can foster tumor progression through a variety of mechanisms. Importantly, obesity is associated with an increased risk for more than a dozen different cancer types.

In addition to being a risk factor for cancer, obesity can influence cancer metastasis, Quail said. She reviewed results from a study which demonstrated that obese patients with breast cancer develop lung and liver metastases roughly two years earlier than non-obese patients, a finding that did not hold true for brain and bone metastases. This suggests that there are site-specific effects of obesity on different tissue microenvironments, Quail noted.

The Quail laboratory is specifically interested in obesity-driven breast cancer metastases in the lung. Quail detailed her work which illustrated that neutrophils accumulate in the lungs of obese mice, leading to an increase in lung metastasis. Additional work in mice revealed that this process is driven by the production of reactive oxygen species and NETosis (a process which releases NETs, or neutrophil extracellular traps), disrupting the integrity of the endothelium and enabling the extravasation of tumor cells into the lung in obese animals, Quail explained.

To understand if these findings had translational relevance, Quail and colleagues analyzed human lung metastasis samples using mass cytometry imaging and found a significant correlation between BMI (for body mass index) and markers of NETosis. They also wanted to elucidate if weight loss had an effect on lung inflammation. Quail and colleagues evaluated serum samples before and after a weight loss intervention among morbidly obese women and found that participants who lost 10 percent of their body weight had a significant reduction of IL5 and GM-CSF, two key inflammatory factors that facilitate the expansion and trafficking of neutrophils into the lung in obese mice.

“These data suggest that weight loss may be partially effective in reversing some of the pro-metastatic effects of obesity,” Quail said.

Check back for continued coverage of this meeting and other special conferences on this blog.