Alcohol and Cancer Risk: How Much is Too Much?

When the COVID-19 pandemic forced much of the world to shut down, and many days seemed bleak, it was easy to joke about the allure of a splash of rum in a morning coffee, or a cold beer at the end of the day.

It was also easy to ignore a steady drumbeat of studies that showed that alcohol consumption is undeniably linked to cancer risk.

Beyond the jokes, alcohol consumption rose during the pandemic. Numerous studies indicated that people were drinking more alcohol, with stress, increased access, and boredom cited as factors.

A study published in December 2020 in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health showed that 60 percent of respondents reported increased drinking during the pandemic. (Thirteen percent said they were drinking less.) The study also showed that 34 percent of respondents reported binge drinking and 7 percent reported extreme binge drinking.

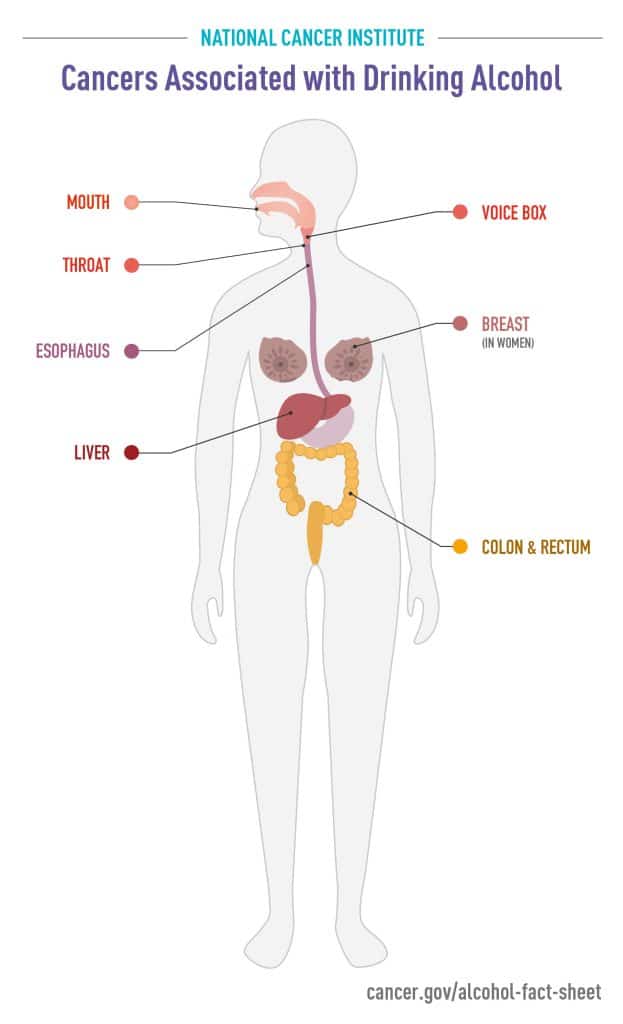

Since then, new research has underscored what many experts have long known: Alcohol increases the risk of many kinds of cancer. An International Agency for Research on Cancer study published in August 2021 in The Lancet Oncology found that globally, more than 741,000 cases of cancer diagnosed in 2020 were attributable to cancer. That figure accounts for 4.1 percent of global cancer cases, and encompassed esophageal, mouth, larynx, breast, colorectal, and liver cancer. Men accounted for about 75 percent of the alcohol-related cases.

Many smaller studies over the past decade had also implicated alcohol in cancer risk. For example:

- A report from the World Health Organization (WHO) found that alcohol caused 7 percent of all new breast cancer cases in WHO’s European region.

- A large study of African American women found that women who drank more than 14 drinks in a week were 33 percent more likely to develop breast cancer than those who drank four or fewer drinks per week.

- The U.S. Surgeon General’s Office discussed cancer risk in its 2016 report, “Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health.”

- The World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research concluded that drinking 30 grams or more of alcohol per day increased the risk of colorectal cancer.

To discuss the latest studies, and to identify “knowledge gaps” in research on alcohol and cancer, in December 2020, the National Cancer Institute convened a workshop and webinar titled Alcohol as a Target for Cancer Prevention and Control: Research Challenges. Conducted virtually, the workshop summarized recent studies on the role of alcohol across the cancer continuum; assessed what researchers still need to learn; and provided a forum for conversations about how public policy and communication could be used to increase public awareness on this topic.

Susan Gapstur, PhD, MPH, a well-known cancer epidemiologist, was a co-chair of the webinar, and recently summarized the event in a paper in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR).

Gapstur is quick to assert that links between alcohol and cancer have long been known. “We’ve known about this connection for more than 30 years; this is not our first conversation on the topic,” she said. Indeed, WHO’s International Agency for Research on Cancer first classified alcoholic beverages as carcinogenic in 1987. Since then, there is now sufficient scientific evidence showing that alcohol plays a causal role in cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract (including oral, pharynx, and larynx cancers, as well as squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus), breast, colorectum, and liver.

For other types of cancer, including prostate cancer, pancreatic cancer, and melanoma, for example, the findings aren’t as clear, Gapstur said. Panelists in the workshop and webinar believe that further research could help clarify the associations of alcohol with risk of cancer types for which the evidence is inconclusive.

As discussed during the workshop and webinar, studies have shown that only 33 to 46 percent of Americans are aware of the connections between alcohol and cancer risk.

Gapstur said that the messages on alcohol and cancer may have gotten muffled amid public health campaigns against drunk driving, underage drinking, and binge drinking. Panelists found ample opportunities for research focused on strengthening accurate messaging on alcohol and cancer, including messaging by clinicians and public health organizations.

How does alcohol increase cancer risk?

This fundamental question does not have one simple answer, Gapstur noted. For example, in the case of liver cancer, heavy alcohol consumption is known to cause cirrhosis, a chronic condition in which healthy cells in the liver are replaced with scar tissue, often causing inflammation and ultimately, leading to liver cancer.

For other cancer types, carcinogenesis may occur when ethanol, the main component of alcohol, is metabolized into acetaldehyde, a known cancer-causing agent. Acetaldehyde interferes with DNA synthesis and repair and causes cytotoxicity and mutagenicity, Gapstur’s paper states. It also leads to the formation of DNA adducts—segments of DNA bound to cancer-causing chemicals.

Further research into the mechanisms of alcohol’s effect on cancer risk could increase understanding of other factors that may interact with alcohol to increase cancer risk.

How much is too much?

There’s an accepted truth among researchers investigating the role of alcohol in cancer: Many people drink more than they say they do.

“Underreporting” is common. There’s also a high degree of variability in how people report serving sizes of alcohol. One person may have a standard serving of 5 ounces of wine, while another may fill a 16-ounce wineglass to the brim, and both may report that they had one glass.

There are some guidelines. The U.S. government’s Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025, recommends that people who do not presently drink alcohol continue to abstain. Those who do choose to drink should limit consumption to two drinks per day for men and one drink per day for women.

The NCI workshop/webinar summary pointed out that few surveys have tried to capture information on alcohol consumption over a lifetime. The age at which one begins drinking, levels of consumption, and episodes of binge drinking could potentially play a role in cancer risk, but that history is rarely available. Also, there is little research on what happens when someone stops drinking, Gapstur said.

“The workshop and webinar examined many cross-cutting scientific evidence gaps. Taken together, if these gaps are filled, they could potentially change what we say about the effects of alcohol on cancer risk, how we communicate that evidence and affect drinking behaviors,” she said.

It’s the holiday season …

With all this information fresh in our minds, how should we approach this holiday season? When global health organizations say that any amount of alcohol raises the risk of cancer, should we abstain completely?

“I think we need to be smart about our consumption.” Gapstur said. “Having a glass of wine or other alcoholic beverage occasionally is unlikely to be harmful. But we need to be aware and understand the risks of consumption, and when you’re balancing those risks, you should be mindful of the full body of evidence of the health effects of drinking.”