Annual Meeting 2022: T Cells Provide Hope for Cancer Patients Facing COVID-19

Since COVID-19 first began its siege on the world, much of our scientific knowledge about the disease—and its source virus, SARS-CoV-2—has changed and evolved. One thing that has remained clear, however, is that cancer patients face disparate burdens from both the disease and its effects on health care systems.

The American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) has monitored the interplay between COVID-19 and cancer since the beginning, providing the latest information to researchers, health care providers, and patients. In February 2021, the AACR Virtual Meeting: COVID-19 and Cancer convened researchers from around the world who discussed topics such as the effects of chemotherapy on COVID-19 risk, the effects of immunotherapy on severe disease, and ways to improve cancer screening rates when access was limited. One year later, the AACR Report on the Impact of COVID-19 on Cancer Research and Patient Care paired patient stories with cutting-edge data about how the pandemic reshaped cancer discovery and treatment. The Cancer Research Catalyst blog has published over 50 posts discussing COVID-19, and the AACR has publicly rallied for access to vaccines and boosters for cancer patients and their caregivers.

While vaccines have calmed fears and quelled many of COVID-19’s worst effects, cancer patients do not always reap the same benefits from vaccination as their healthy peers. How has our scientific knowledge expanded to help those who do not respond well to vaccines?

At the AACR Annual Meeting 2022, held in New Orleans April 8-13, researchers presented new discoveries about how different types of immune cells respond to COVID-19 vaccines, including ideas for improving responses in patients with cancer.

The Promise of T-Cell Responses

Many cancer patients experience some form of immune deficiency along the course of their disease, either due to the cancer or to its treatments. Patients with blood cancer are especially affected; hematological cancer development can shift the relative proportions of immune cells, making patients more susceptible to infection, and some immunotherapies that target hematological malignancies catch healthy immune cells in the crossfire.

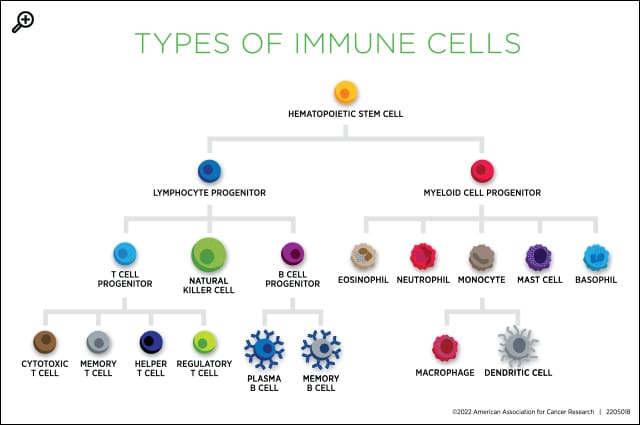

A common immune deficiency among these patients is a lack of B cells, the type of cell that produces antibodies. Antibodies bind to an infected cell and act as a beacon, summoning other immune cells, such as T cells and macrophages, to kill the infected cell.

One key effect of vaccination is the production of memory B cells, which wait in lymphoid organs for signs that an infection has returned. If they encounter the infection again, they stimulate the rapid production of targeted antibodies, potentially enabling a more robust response than to the first infection.

If patients cannot produce and maintain B cells, antibody-mediated responses cannot occur, and memory B cells cannot be stored for future protection against the disease. As vaccine programs rolled out across the country, researchers confirmed that cancer patients with B-cell deficiencies had poor responses to vaccination—including those receiving any form of treatment as well as those receiving stem cell transplants or CAR T-cell therapy. Boosters benefitted some patients, but many still have limited protection from the virus.

Antibody-mediated responses, however, are not the only tool in the immune system’s arsenal for building immunity against antigens it has encountered previously. A handful of researchers are turning their attention to T cells, which remain intact in patients with B-cell immunodeficiencies.

During a session titled “Vaccine Effectiveness in Cancer Patients with Immunotherapy,” Paolo Ghia, MD, PhD, deputy director of the Division of Experimental Oncology, group leader of the B-cell Neoplasia Unit, and head of the strategic research program on chronic lymphocytic leukemia at Università Vita-Salute San Raffaele in Italy, reviewed some recent studies on T-cell vaccine responses in patients with hematological malignancies. Although one study showed a fairly linear correlation between antibody titers and activation of T cells specific to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, Ghia observed that several patients fell outside the linear curve.

Indeed, in another study, researchers found that 86 percent of patients with blood cancer exhibited T-cell responses, including 74 percent of patients with no SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. In yet another study, researchers measured activation of SARS-CoV-2-directed T-cells in patients with and without SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and found that many antibody-negative patients were capable of robust T-cell activation.

“A few studies have shown that T-cell responses may be better maintained or induced compared to serological responses,” Ghia said. “There is hope for these patients, at least in terms of T-cell protection.”

In a minisymposium titled “COVID-19 and Cancer,” Djordje Atanackovic, MD, medical director of the Fannie Angelos Cellular Therapeutics Laboratory and director of cellular and vaccine immunotherapy at the Greenebaum Cancer Center of the University of Maryland, and Elizabeth Ahern, MBBS, PhD, FRACP, a medical oncologist at Monash Health in Australia, also reported promising data on T-cell responses to COVID-19 vaccination.

Ahern studied immune responses in patients with blood cancers and solid tumors and found that both populations had a robust induction of T-cell activation following two doses of vaccine, as evidenced by the production of multiple activation-related cytokines in response to SARS-CoV-2 antigen.

In patients who received CAR T-cell therapy, Atanackovic and colleagues observed a robust increase in SARS-CoV-2-directed T cells after vaccination; the average level of T-cell activation was comparable to that of individuals with a prior COVID-19 infection and slightly higher than that of control individuals without cancer.

“We showed that the same T cells were not only able to recognize the original version of the virus but also the omicron variant as well,” Atanackovic continued.

Hope for the Future

Recognizing the importance of T-cells in mediating COVID-19 immunity provides an opportunity to design specialized vaccines for patients who rely chiefly on T-cell responses to protect them from the disease. Researchers have already begun production and clinical testing on such vaccines, including one presented during the “COVID-19 and Cancer” minisymposium.

While humoral responses are the key target of most vaccines, Claudia Tandler, MSc, a graduate student at the University of Tübingen, and colleagues have designed a vaccine called CoVac-1, which uses antigens selected to leverage the T-cell response. CoVac-1 is a peptide-based vaccine; instead of using mRNA instructions for a large piece of a single protein, CoVac-1 involves the injection of six small protein fragments. These antigens are derived from different parts of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, meaning several independent mutations would need to occur for the virus to develop vaccine resistance, Tandler said.

“CoVac-1-induced T-cell immunity is far more intense and broader, as it is directed to different viral components than mRNA-based or adenoviral vector-based vaccines that are limited to the spike protein and are thus prone to loss of activity due to viral mutations,” she explained in a press release about the study.

Tandler and colleagues enrolled 14 patients with B-cell deficiencies in a phase I/II clinical trial in which the patients received a single dose of the vaccine and were monitored for up to six months. Two weeks after vaccination, 71 percent of patients were able to mount T-cell responses to SARS-CoV-2. The response rate rose to 93 percent at four weeks post-vaccination.

The researchers also measured the potency of these responses and found them to exceed T-cell responses observed in immunocompromised patients after vaccination with an mRNA vaccine, as well as T-cell responses from non-immunocompromised individuals after a COVID-19 infection.

“Based on these promising results, we are currently preparing a phase III approval trial, because we think that CoVac-1 has the potential to help protect this immunocompromised patient cohort from severe courses of COVID-19,” Tandler said.