Broadening Clinical Trial Eligibility: A Tricky Balancing Act

The scientific method is rooted in the careful control of materials, variables, and procedures. Any deviations between experimental groups may introduce bias that could compromise the validity of the findings.

It’s a simple enough principle when at the lab bench, but at the bedside, things are rarely so black and white. Patients who receive a new cancer therapy are inherently heterogeneous, harboring a myriad of comorbidities and medical histories that can complicate their response to the treatment.

Accordingly, strict clinical trial eligibility criteria can ensure patients with comorbidities aren’t inadvertently harmed by drugs’ side effects while also minimizing the odds that a potentially effective drug is deemed ineffective. However, this practice may prevent some patients from receiving potentially life-saving cancer treatment, and when the drug reaches the market, clinicians may not have sufficient data to determine how well it works in patient populations that were underrepresented in the trial.

So, how do researchers ensure a drug is being tested fairly but is also safe and effective in a population of patients who are anything but uniform?

On the heels of recent studies hinting at the benefits of loosening the reigns, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued three draft guidances intended to help clinical researchers mindfully design the eligibility criteria for their trials. Can an overhaul of the status quo help strike the ideal balance between rigorous science and inclusive clinical practice?

The Role of Clinical Trial Eligibility Criteria

In their draft guidances, the FDA stated that, “The purposes of eligibility criteria for clinical trials are to select the intended patient population and reduce potential risks to trial participants.”

On the surface, a lot of these are straightforward. If you’re testing a drug for kidney cancer, for example, patients need to have kidney cancer. For some therapies—especially targeted therapies and immunotherapies—patients’ tumors may need to express certain markers that the drug was designed to target.

Certain obvious safety risks may also affect eligibility criteria. For instance, patients may be excluded if they’re taking other medications that may interact with the study medication. Alternatively, if the study treatment is known to be particularly taxing on the liver, a preexisting liver disease could put patients at unnecessary risk.

But often, eligibility criteria require optimization so they aren’t unnecessarily stringent, explained Hans Gelderblom, MD, chair of the Department of Medical Oncology at Leiden University Medical Center in the Netherlands. Gelderblom and colleagues recently published a study in Clinical Cancer Research, a journal of the AACR, to assess the effect of protocol waivers on the outcomes of patients treated in a large clinical trial.

Failure to optimize the criteria may result in cases such as a patient with liver disease getting excluded from a trial for a drug metabolized by the kidneys, Gelderblom explained. In fact, the FDA cited strict requirements for laboratory values related to kidney and liver function as one of the most common reasons for clinical trial exclusion.

Eligibility may also necessitate laboratory values falling within certain ranges, with no tolerance for values slightly outside those parameters. Careful timing of imaging scans or biopsies to chart the tumor’s response to treatment can also be included in the eligibility criteria, but patients may not be able to meet those deadlines to the letter.

“Unnecessarily strict safety criteria should, where possible, be eliminated when setting up new molecularly driven trials,” Gelderblom said. “This is especially relevant when the study population concerns patients without other treatment options.”

FDA Recommendations for Striking a Balance

In Gelderblom’s study, the most common reasons for protocol exceptions were out-of-range laboratory values and exceptions from required laboratory tests, including biopsies. One of the FDA’s three draft guidances, “Cancer Clinical Trial Eligibility: Laboratory Values,” addressed why laboratory tests are a common source of eligibility restrictions and how they can be potentially reconsidered to allow more patients to enroll.

Studies have shown that eligibility criteria based on laboratory values do not vary much between different clinical trials for cancer therapies, suggesting that they may be carried from trial to trial without careful consideration of which comorbidities may actually pose a risk. Further, reference ranges for “normal” laboratory values may differ based on age, race, and ethnicity, which may enhance disparities in enrollment if these differences are not accounted for.

To solve this, the FDA proposes that trialists provide a clear scientific rationale for each restriction and review them as additional data become available (i.e., between clinical trial phases). The FDA also recommends accounting for disease-relevant changes to organ function. For instance, since liver dysfunction may be more prevalent among patients with liver cancer it should not preclude enrollment.

In “Cancer Clinical Trial Eligibility Criteria: Washout Periods and Concomitant Medications,” the FDA raised similar concerns about the exclusion of patients taking other medications or the mandatory delay between the cessation of one treatment and the start of another. While such restrictions are sometimes important to prevent dangerous drug interactions and may be necessary to accurately test a new therapy’s accuracy, broad exclusion criteria are often employed that may unnecessarily hinder enrollment. As older patients, especially those with cancer, are more likely to take multiple maintenance medications than the general population, they may be more likely to be excluded.

Similar to the guidance for exclusion criteria based on laboratory values, the FDA recommends having a specific rationale for each contraindicated drug class, as well as evidence-based mandatory washout periods that account for the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of the treatment being ceased.

Finally, the FDA addressed eligibility criteria that account for a patient’s “performance status,” or their ability to perform normal daily tasks. Patients with a low performance status are often excluded because they may be more susceptible to side effects, which could more negatively impact their quality of life and skew data related to adverse events.

However, performance status scores are subjective, especially in patients over 65, and may not necessarily indicate additional risk, the FDA explained in “Cancer Clinical Trial Eligibility Criteria: Performance Status.” If a treatment more adversely impacts patients with low performance status, the FDA argued, that data should be known so patients and physicians can be best informed when the drug reaches the market. The FDA recommends including patients with moderate to low performance status whenever possible. If necessary for data analysis, researchers may exclude patients with low performance status from efficacy analyses or stratify patients based on performance scores.

Benefits for Patients and Researchers

The study by Gelderblom and colleagues tested how some of the FDA’s ideas might shape patient outcomes in practice.

Sometimes, patients may be considered for eligibility requirement exemptions, wherein qualified physicians review a patient’s situation and decide whether their enrollment poses a significant risk or may affect the data. Gelderblom and colleagues sought to determine how these exemptions—and, by extension, the broadening of clinical trial eligibility criteria—might affect patient outcomes.

Gelderblom and colleagues assessed survival and response rates for 1,019 patients enrolled in the Drug Rediscovery Protocol (DRUP) trial, a Dutch pan-cancer basket/umbrella trial that matches treatment-refractory patients with off-label targeted therapies based on their tumor’s molecular profile; 82 of these patients received a waiver to enroll despite not meeting all eligibility criteria.

Forty percent of patients who received a waiver experienced a clinical benefit, compared with 33% of patients who met all eligibility criteria; median overall survival was also similar (11 months versus 8 months, respectively). Severe side effects affected 39% of patients granted a protocol waiver and 41% of patients without waivers.

“These findings advocate for a broader and more inclusive design when establishing novel trials, paving the way for a more effective and tailored application of cancer therapies in patients with advanced or refractory disease,” Gelderblom said in a press release about the study.

Boosting the number of patients eligible for clinical trials may have additional benefits. In all three draft guidances, the FDA stressed that loosening eligibility criteria may speed up the enrollment process and allow trials to proceed faster. It may also help broaden the diversity of the trial population, a topic tied closely to a related FDA draft guidance issued in 2022 and updated most recently in June 2024.

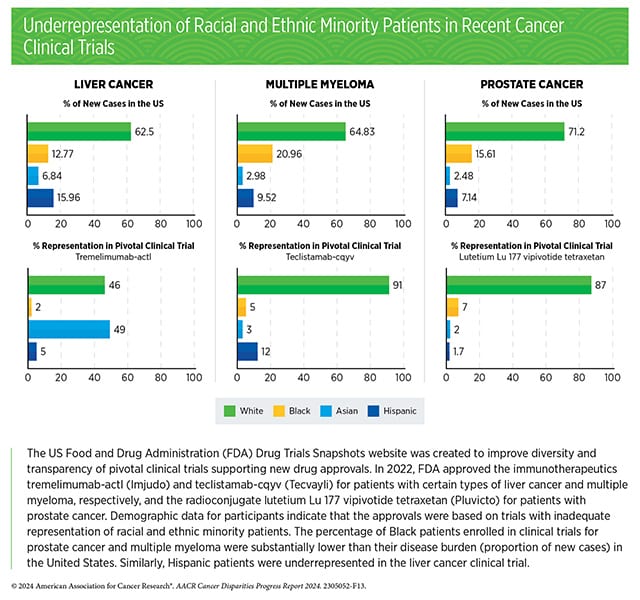

According to the AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2024, almost 90% of pivotal clinical trials supporting the approval of novel cancer therapeutics between 2015 and 2021 lacked adequate representation of Black patients, and 73% lacked adequate representation of Hispanic patients. Further, in a meta-analysis of phase III trials of patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), over 70% of enrolled patients were under age 65, despite the median age of AML diagnosis being 69.

“Fostering efficient and more patient-centric clinical trial designs has long been a priority for the FDA’s Oncology Center,” said Paul G. Kluetz, MD, deputy director of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence, in a statement about the new draft guidances. “Assuring that eligibility for a cancer trial is not overly restrictive can facilitate enrollment of a more diverse and ‘real-world’ group of patients that are more reflective of who will use the therapy in routine care if approved.”

The three guidances described here are the latest in a widespread effort by the FDA to broaden cancer clinical trial eligibility criteria. Five other draft guidances related to this topic were issued previously and can be found on the FDA website. These draft guidances are not yet finalized, but the finalized versions will contain nonbinding recommendations that represent the current thinking of the FDA.