Lymphomas in the Young and the Old: How Do They Differ?

While cancer is often regarded as a disease of old age, 84,100 adolescents and young adults (AYAs) in the United States are expected to be diagnosed with some form of the disease this year, with Hodgkin lymphoma representing a large portion of these cases. Although the risk of this immune cell cancer wanes after early adulthood, it rises again later in life, starting around age 60.

Hodgkin lymphoma, therefore, may be considered a disease of both youth and old age—but are the Hodgkin lymphomas that develop in older adults the same as those found in young patients?

To answer this question, Lisa G. Roth, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine, and colleagues set out to characterize the molecular features of Hodgkin lymphomas across the age continuum. She reported their findings at the Advances in Malignant Lymphoma: Maximizing the Basic-translational Interface for Clinical Application scientific meeting, which was organized by the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) in cooperation with the International Conference on Malignant Lymphoma.

The results were also published in the AACR journal Blood Cancer Discovery.

The Effect of Age on Hodgkin Lymphoma

As Roth explained in her meeting presentation, molecular characterization of Hodgkin lymphoma cells can be challenging due to their sparseness in tumor tissue, which is primarily comprised of non-lymphoma immune cells and components of the complex tumor microenvironment. To overcome this hurdle, she and colleagues processed patient samples with flow cytometry to separate the lymphoma cells from other cell types, using several lymphoma-associated biomarkers to isolate enough cancer cells for high-throughput sequencing.

Whole exome sequencing of lymphoma cells from 145 patients—aged 11 to 85 years—demonstrated that lymphomas in younger patients (median age of 30) were significantly less likely to express beta-2-microglobulin (B2M), a gene whose expression is associated with poor prognosis.

Since loss of B2M expression is usually a result of genetic mutations, this finding suggested “that there are differences across the age spectrum with regards to genetics in Hodgkin lymphoma,” Roth noted.

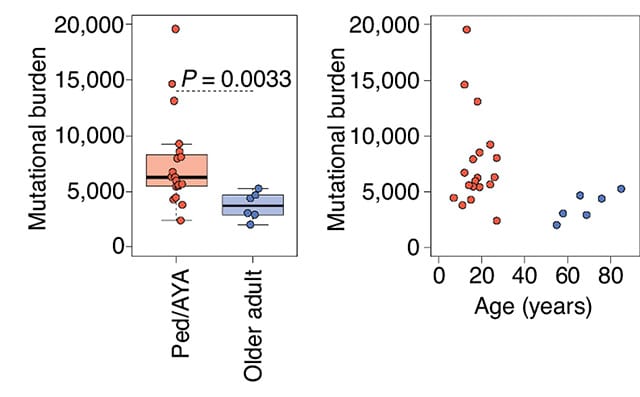

Roth and colleagues then turned to whole genome sequencing for a more comprehensive characterization of the molecular alterations present in Hodgkin lymphomas, analyzing samples from 25 patients representing two age groups: pediatric/AYA patients aged 7-27 years, and older adult patients aged 55-85 years.

Whole genome sequencing of these samples revealed that lymphomas from the younger cohort had significantly more mutations across the genome, even after accounting for technical and biological differences between the groups, such as sequencing coverage, tumor histology, and viral infection.

The higher tumor mutational burden in younger patients appeared to be driven by two “clock-like” mutational signatures, SBS1 and SBS5, that tend to accumulate steadily over time. Roth and colleagues estimated that the mutations within this signature accumulated up to six times more rapidly in lymphomas from pediatric/AYA patients compared with those from older adults, which could explain the greater number of mutations in the younger cohort.

The Implications of Age-related Molecular Differences

Defining the molecular features of cancer cells can reveal how cancers develop in different populations and can inform treatment. Roth noted that while patients are often grouped as either pediatric (under age 18) or adult (over age 18), the molecular differences she and colleagues observed did not occur before and after age 18 but instead occurred between the age groups in which Hodgkin lymphomas are most frequently diagnosed—that is, between pediatric/AYA patients and older adults.

“How can we better group patients based on the biology of their disease rather than ‘pediatric’ versus ‘adult’?” Roth posed, noting that using the “arbitrary cutoff” of age 18 to stratify patients has led to vast differences in how patients are treated even though the biology of the cancer does not change until a much later age.

Understanding how the molecular features of lymphomas vary across the age spectrum could help researchers fine-tune disease classification and better stratify patients for treatment, Roth said. She added that early results indicate that the age-related molecular differences appear to correlate with treatment outcomes, suggesting that these molecular features may have therapeutic implications.