The Affordable Care Act’s Impact on Access to Cancer Care

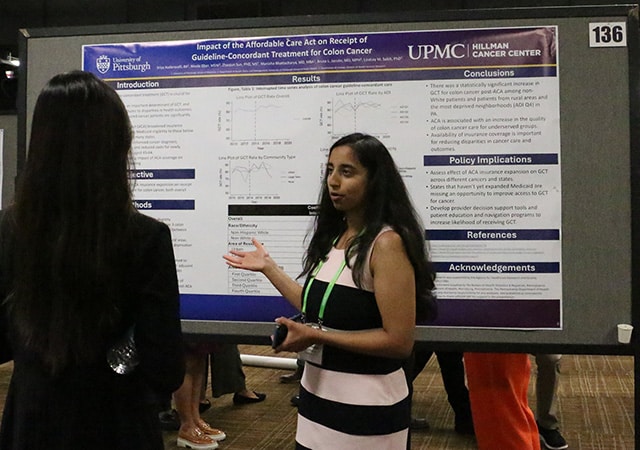

Has the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) improved access to care for cancer patients? It is a question several researchers have asked and attempted to answer in recent years, including Sriya Kudaravalli, a third-year medical student at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, who presented results from a study at the 17th AACR Conference on the Science of Cancer Health Disparities in Racial/Ethnic Minorities and the Medically Underserved, held September 21-24.

“While previous studies have explored the impact of the ACA on cancer screening, stage at diagnosis, mortality rate, access to treatment, and insurance coverage of cancer patients, research regarding the impact of the ACA coverage expansions on quality of cancer care specifically is lacking,” Kudaravalli said during her presentation. “And quality of cancer care can be determined by whether patients are receiving guideline-concordant treatment or not.”

Kudaravalli explained that access to insurance is an important factor in whether a person receives guideline-concordant cancer care, which is associated with improved outcomes, including survival. The ACA’s Health Insurance Marketplace started offering coverage in January 2014. To mark the 10-year anniversary, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) released a report, in which it states that the rate of Americans of all ages without health insurance dropped from 14.4% to 7.7% between 2013 and the third quarter of 2023.

Kudaravalli and her colleagues wanted to see if this coverage expansion led to better cancer care for people across socioeconomic factors, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, insurance status, community type, and area deprivation index (ADI). They chose to examine data from the Pennsylvania Cancer Registry, in part, because Pennsylvania is one of the most populous states to expand comprehensive Medicaid coverage under the ACA. Between 2010 and 2019, they found 3,290 patients, ranging in age from 26 to 64, who had been diagnosed with stage 3 colon cancer.

Then, using medical literature and the criteria established by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, they defined guideline-concordant care for stage 3 colon cancer as the use of adjuvant chemotherapy and the resection of affected regional lymph nodes. Next, they compared the trend in guideline-concordant treatment received pre- and post-ACA implementation. They focused on groups typically thought to be underserved in health care, including those who identify as non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic, those in rural areas, and those in higher ADI neighborhoods. ADI scores, which rank neighborhoods by socioeconomic disadvantage based on variables such as income, education, employment, and housing quality, were grouped into quartiles, with quartile 1 being the least disadvantaged and quartile 4, the most disadvantaged.

Over the course of the study period, they found the receipt of guideline-concordant care increased after the implementation of the ACA on average per year for non-white patients (7.8%), those in rural areas (7.7%), and those in ADI quartile 4 neighborhoods (3.5%). Kudaravalli attributed these changes to the combined effect of Marketplace and Medicaid expansions, as well as other ACA provisions that helped provide continuity of care through access to services like reliable transportation to health care appointments.

“When it comes to policy implications, states that haven’t yet expanded Medicaid should seek to do so because they’re missing an opportunity to improve access to guideline-concordant treatment for cancer,” Kudaravalli said.

Access to Surgery for Prostate, Lung, and Colorectal Cancer

Researchers at the University of Pittsburgh School of Public Health also used data from the Pennsylvania Cancer Registry between 2010 to 2019 to see whether the ACA led to changes in receipt of surgery related to prostate, lung, or colorectal cancer at National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer centers (NCI-CCC) and Commission on Cancer (CoC) accredited hospitals. Their focus was on identifying if access increased for those most likely to be newly eligible for coverage by comparing patients in counties with high uninsurance rates pre-ACA to counties with a lower baseline for uninsurance.

In a paper published in Health Services Research, the authors point out that not only do NCI-CCC and CoC institutions have a workforce with greater expertise in cancer, but cancer mortality rates also tend to be lower for multiple prevalent cancer types, including lung, breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer. In the study, they identified a total of 36,519 patients who met the following criteria: they were between the ages of 26 and 64; diagnosed with lung, prostate, or colorectal cancer; received surgery as their first course of treatment; and they had corresponding discharge records from the Pennsylvania Health Care Cost Containment Council. Of the 148 hospitals where these patients had surgery, three were both NCI-CCCs and CoC accredited while another 53 were only CoC hospitals.

Over the study period, the number of patients who received surgery for cancer at NCI-CCCs increased by 6.2 percentage points. This change was highest among those who received surgery for colorectal cancer and those in urban areas. The authors also noted that a sharper increase was seen after 2016 when Medicaid expansion was implemented in Pennsylvania. While surgical care also increased at CoC institutions, it was not by a statistically significant margin.

Addressing Delays in Treatment

The ACA has also helped to close the gap in other disparities related to cancer care, according the AACR Cancer Progress Report 2024. In one example, researchers at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center examined whether the ACA led to improvements in delays prior to breast cancer surgery for underrepresented minorities, which is associated with worse outcomes. They examined data from the National Cancer Database between 2010 and 2017, comparing the 19 states that adopted Medicaid expansion on January 1, 2014, to 19 states that did not. The cohorts from expansion states included 104,569 women with stage 1 or 2 breast cancer between the ages of 40 and 64 versus 116,315 patients in the nonexpansion cohort.

Overall, the researchers found that the rate of delayed surgery dropped from 9.8% to 8.4% after Medicaid expansion for patients belonging to racial and ethnic minority groups who had Medicaid insurance or were uninsured. The drop was largest among those who were in fact insured with Medicaid (a 2.5% reduction) and for those who had stage 2 breast cancer (a 5% decrease). The researchers did not find any reduction among racial minorities with private insurance in expansion states nor in states that did not expand Medicaid.

In another example cited in the report, a team consisting of several of the researchers from the study above also used data from the National Cancer Database to examine disparities in the initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. While the optimal timing of chemotherapy following surgery is unknown, longer delays in initiation have been associated with adverse outcomes.

This time they looked at data between 2007 and 2017 from the 19 states that implemented Medicaid expansion in January 2014 for patients with stages 1-3 breast cancer who had chemotherapy within six months after surgery. Overall, out of a total of 100, 643 patients, they found the number of women who experienced a delay in starting adjuvant chemotherapy declined from 23.4% to 21.9%. It dropped from 22.2% to 19% among whites, 33.2% to 27.9% in Blacks, and 30.8% to 24.5% in Hispanics. Asian American or Pacific Islander patients also saw a marginally statistically significant decline from 25.2% to 20.4%, but out of a smaller sample size then the other demographics.

Some Barriers to Care Remain

However, some individuals who have received access to coverage through the ACA Marketplaces still face hurdles. In a study published in JAMA Network Open, researchers at the University of Toronto and Emory University examined insurance denials for seven preventive services recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, including breast and colorectal cancer screening. These services were meant to be exempt from cost-sharing under the ACA, but some patients have still had to pay out-of-pocket costs either due to errors or misunderstandings from patients, insurance companies, or hospital staff.

Using claims and remittance data from Symphony Health Solutions of patients insured through employer-sponsored plans or the ACA Marketplaces between 2017 to 2020, the researchers identified 1,535,181 patients who received a combined 4,218,512 preventive services. In total, 1.34% of preventive claims were denied, including screening for diabetes, depression, cholesterol, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, as well as contraceptive administration and wellness visits. The groups who experienced the highest rates of denials across all services included those making under $30,000 annually (2.11%), those with a high school degree or less (1.79%), as well as Asians (2.72%), Hispanics (2.44%), and non-Hispanic Blacks (2.04%).

While a review published in Current Oncology found that the overall impact of Medicaid expansion under the ACA on cancer care has been positive, it also noted that variations in care like this still exist across racial and ethnic minority populations, those in rural areas, and individuals in lower socioeconomic brackets. To better understand these gaps, the authors call on future studies to focus on the effects of social determinants of health and the various ACA adoption models used by different states, and to continue with longer follow-up studies to get a clearer picture of the ACA’s impact over time.