Structural Racism and Cancer Disparities: Looking at All the Angles

Melissa Davis, PhD, is putting health disparities under a lens. One that can take an aerial view of the discriminatory structural barriers responsible for inequities, observe the potential ramifications of those barriers, and zoom in on each little detail of a tumor cell to see how it is being impacted, all while tracing how an individual’s genetic background also plays a role.

“We know that structural racism becomes biology, but how does it become tumor biology?” posed the director of the Institute of Translational Genomic Medicine at Morehouse School of Medicine during the scientific keynote of the 17th AACR Conference on the Science of Cancer Health Disparities in Racial/Ethnic Minorities and the Medically Underserved. “[This] research equity lens … will improve precision. We’ll be able to impact how and why we are studying different populations in a diverse patient cohort. And then how these precision medicine tools will actually become precise.”

The lens she refers to is team SAMBAI (Societal, Ancestry, Molecular, and Biological Analyses of Inequalities), a research project led by Davis and funded by Cancer Research UK and the National Cancer Institute as the first awardee of the Cancer Grand Challenges to focus on health inequities. The team’s logo is a lens meant to represent the different methodologies the team will use to study breast, prostate, and pancreatic cancers among the African diaspora and attempt to zero in on answers that can help address health disparities.

But to understand how Davis arrived at this approach, you first need to understand structural racism and the role it plays in health. Fortunately, not only did Davis provide a brief history lesson, but it was also a theme woven throughout the conference.

What Is Structural Racism?

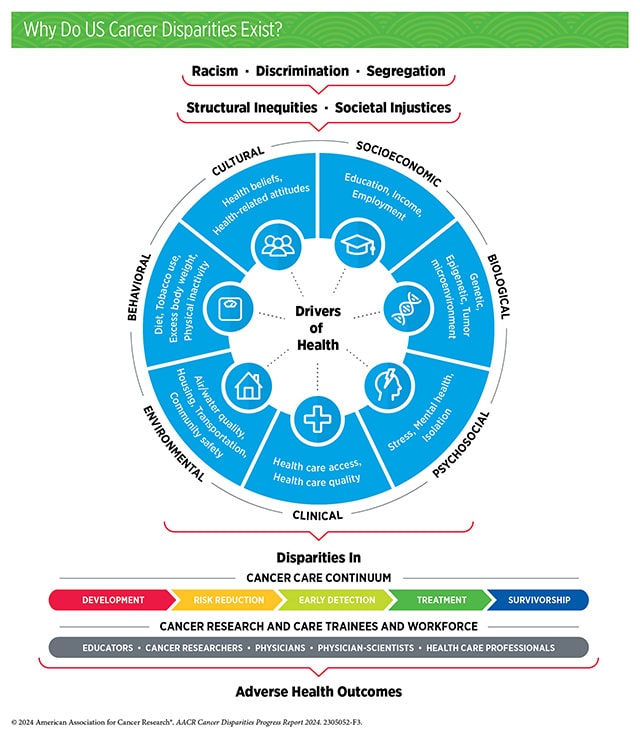

Structural racism, as it was defined by Lauren Barber, PhD, of the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University, during a plenary on that very topic, is the most complex form of racism as it involves “multiple systems and institutions that interact to assert racist policies, practices, and beliefs about people in a racialized group.” These policies can shape factors like education, employment, housing, health care, political participation, and criminal justice—often in interconnected ways that can impact individuals on multiple levels.

In addition to her background as a molecular geneticist turned genomicist, Davis’ life experiences have also helped her to understand how society can impact the science of health disparities. As a product of desegregation practices in the South, she has seen this firsthand. She is also well aware of the history of health injustice in this country, like the “One Drop Rule” which classified anyone with even one drop of “black blood” as African American—no matter how remote the connection—and serves as reminder of how scientists must get to the heart of how populations actually differ.

For example, while socioeconomic status (SES) likely plays some role in disparities related to access to care, Davis also pointed out how statistics show Black patients who live in affluent areas still have higher mortality rates in prostate and breast cancer than their white counterparts who live in poverty.

Under Pressure

Davis and other researchers are trying to determine whether some of these disparities could be caused by the toll chronic stress can take on a person’s body, also known as allostatic load. Among them is Adana A. M. Llanos, PhD, MPH, of the Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center at Columbia University, who explained during a session on structural racism and cancer how a combination of neighborhood disinvestment, racial residential segregation, and the lived experiences of being Black in America can contribute to stress responses that trigger inflammation that could have a negative molecular impact on cells. In one study, Llanos noted how higher allostatic load scores based on biomarker data from samples previously collected from Black women and calculated 12 months prior to breast cancer diagnosis indicated almost twofold greater odds of a higher-grade tumor.

Llanos also discussed another form of pressure leading to higher cancer risk—the need to adhere to certain beauty standards.

“The connection with beauty products and health equity really stems from the staggering numbers that show products that are overwhelmingly marketed towards female identifying women of color,” Llanos said. “They’re advertised to promote Eurocentric beauty standards, so straighter hair, lighter skin, and all of this advertising drives the sales of products that are toxic.”

As Llanos explained, many commercially oxidative hair dyes and relaxers contain mutagens and carcinogens, including endocrine-disrupting chemicals that promote abnormal physiological functioning. She and her colleagues found that that users of both relaxers and hair dyes had greater than twofold increased risk of breast cancer and those who used these products for more than 10 years or who started before age 12 had larger and more aggressive tumors.

Climate Change: A Threat and Opportunity

Redlining was a decades-long government policy that started in the 1930s in which certain neighborhoods, often based on race or ethnicity, were classified as hazardous or less desirable and denied mortgages or other financial services. The disinvestment in these areas led to declines in infrastructure, green spaces, public transportation, schools, and employment opportunities, all of which have made individuals there, among other things, more susceptible and less able to adapt to the effects of climate change, according to Leticia Nogueira, PhD, MPH, of the American Cancer Society.

During a plenary session that discussed how structural racism, climate change, and cancer disparities are connected, Nogueira explained how redlined areas are more likely to become “urban heat islands” during periods of high temperature because the buildings in these areas are made with impervious surfaces, such as asphalt and concrete, that trap heat. These areas are also more likely to lose power during heat waves, which also means people lose access to air conditioning, if they happened to have it.

How does this impact cancer? Iona Cheng, PhD, MPH, of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) and the UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, found that long-term exposure to higher temperatures leads to worse mortality rates for patients with any disease, but is specifically higher for those with colorectal cancer in lower SES areas compared to higher SES areas.

And it’s not just heat; Nogueira noted how people living in redlined areas may face higher exposure to air pollution because they may live closer to highways or have fewer resources to relocate or deal with the aftereffects of hurricanes, floods, or wildfires.

While all of this may sound dire, Christine Ekenga, PhD, MPH, of the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University, said, “Climate change is often considered the greatest global public health threat, but I think it also may be the greatest global public health opportunity.”

Why? Ekenga explained how working to mitigate climate change often has healthy co-benefits, such as lowering carbon emissions, which could decrease air pollution and hence reduce risks for certain diseases. The same is true for other mitigation factors like increasing green spaces in cities, which could reduce the local temperature.

“There’s so much co-benefits that we are seeing that … it’s really a bright future if we continue to push for the solutions to be implemented,” Nogueira added.

A New Lens on Structural Racism and Cancer

Davis’ team SAMBAI will attempt to touch on all of those areas related to how structural racism impacts cancer and more. One of Davis’ key areas of research has been to examine ancestry’s connection to health disparities. For example, she found that patients with higher amounts of West African ancestry were more likely to have triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) compared to other breast cancer types. Further, she identified African-specific alleles of genes that regulate pathways that may drive some of the phenotypes found in cancer.

Research into genomics and epigenomics will continue in one of the five work packages under SAMBAI, and Davis is already excited about discovering new contigs from the African background. (Contigs are sets of overlapping DNA segments that are used to help map out the genome.)

“The most interesting part about these contigs is that they’re not a part of the human genome reference,” Davis explained. “That means they haven’t been a part of any previous epigenetic study. These are uninterrogated regions of the genome that could potentially be driving … differential expression.”

The other work packages include one on societal and social determinants, which will use surveys to track lived experiences and augment it with other information about societal trauma, such as the impact of being displaced by a hurricane. Another one will focus on exposomics, which will use mass spectrometry readings to measure the exposures to particulates and help to quantify the area-level and the self-reported exposures. The fourth involves tumor immunological profiling and can help inform the stress networks that were uncovered in the societal and social determinants work package or the exposures identified in the exposomics one.

“We’ll be able to give you a data set that allows you to tease apart how the metabolic dysfunction of patients and their genetic background are linked to the specific redlining in their area,” Davis said. “And wouldn’t that be wild to be able to say that the decision on how to treat a patient is contingent on where they live in New York City? Because one of the things we’ve been doing as we treat cancer patients … is send them right back into the area where they got the cancer … without any further information about how or why they had the tumor or how to mitigate against it.”

Communicating the Science

The final package in SAMBAI is dedicated to disseminating all the information they gathered not just to scientists, but to the people within the communities who could most benefit from it. That work will be led by Ricki Fairley, a survivor of stage 3a TNBC and self-proclaimed thriver; the CEO of TOUCH, The Black Breast Cancer Alliance; and the advocate keynote speaker at the meeting.

Fairley started by describing what she deemed a crisis. Compared to white women, Black women with breast cancer have a 41% higher mortality rate, 39% higher recurrence rate, and a 71% higher relative risk of death. Black women under 35 get breast cancer at twice the rate of white women and die at three times the rate. Fairley was also alarmed by the lack of Black individuals included in clinical research for treatments. Citing the AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2024, she noted that 90% of the pivotal clinical trials that supported the approval of 82 novel therapeutics between 2015 and 2021 lacked adequate representation from Black patients.

Fairley said that these disparities, and others, forced her to create a new definition for Black breast cancer: “The constellation of exposures, experiences, and lack of science for black women diagnosed with breast cancer that causes us to face disproportionately worse breast cancer outcomes.”

Fairley said that her job as an advocate is to “eradicate Black breast cancer. That means lending that person in the dark a hand … try to give them the information that they need.”

Through projects like the When We Tri(al) campaign, she has helped increase the participation of Black women in clinical trials by clearing up misconceptions, such as the notion that people may just get a “sugar pill and die.” So far, she has signed up 19,373 Black women for clinical trials.

When she described her ideal clinical trial site, she painted an image of being welcomed into a nice home where someone can care for her kids as she sits for her shot with a warm blanket, a cup of tea, and some Luther Vandross playing in the background.

“That’s how it should because it’s not about science for us, it’s about love,” Fairley said. “It’s about another birthday, another wedding, another family thing, another sunrise. And so, when you guys think about the science, think about how you’re helping someone live longer or have a life.”

She said that should also apply when communicating science. Fairley emphasized using words patients can spell and concepts they can understand, because it needs to come from a voice they can trust. And she encouraged attendees to think about the concept of cultural humility and the need to collaborate with individuals on their terms.

As Davis previously outlined, collaboration is something that is at the heart of the five work packages, as each of the studies can help better inform the others.

Speaking about the end goal of SAMBAI, she said, “One of the hopes is that we’ll deliver a toolkit so that [researchers] can use our multidisciplinary set of workflows in any patient population in the world in any disparity that you want to use it in.”

For more research articles, reviews, and commentaries about disparities in cancer, including the impact of structural racism, check out this collection from the AACR’s peer-reviewed journals.