Creating a World Where Precision Oncology is a Reality for All

By Vivek Subbiah, MD, Sarah Cannon Research Institute

It is both the best of times and a challenging time to be a precision oncologist. Precision oncology is a transformative approach in cancer treatment that leverages comprehensive genomic testing and other methods to better understand the unique biological underpinnings of each patient’s tumor to tailor more effective therapies. While significant and exciting progress is being made in this field, we must also address the challenges of implementing these approaches in the real world, particularly regarding financial considerations and lack of access. Nonetheless, there is hope.

Twenty years ago, they said we could not sequence the human genome. But in 2003, the Human Genome Project accomplished its goal for an estimated $3 billion. Now, in 2024, we can get sequencing for a few thousand dollars in U.S. academic centers and commercial companies. Going by Moore’s Law, the cost is expected to decrease even further.

Within the next decade, I envision a landscape where precision oncology is seamlessly integrated into routine care. This future would be characterized by more precise, effective, and less toxic treatment options, hopefully resulting in improved survival and quality of life for cancer patients earlier and earlier in the disease course. To make this future a reality, however, we will need to address other areas beyond achieving more cost-effective diagnostic tools and therapies.

Identifying the Right Targets for precision oncology

One of the primary challenges in broadly applying precision oncology is the heterogeneity of tumors. Although significant progress has been made in identifying better targets for cancer therapy, the molecular portrait of a tumor encompasses much more than just genomics. This situation can be likened to the story of the six blind scientists and the elephant, where each scientist describes the animal based only on the part they touch—the tusk, tail, trunk, ear, etc.—missing the whole picture.

In this context, genomics represents just one piece of the puzzle. The other critical components include proteomics, microbiomics, immunomics, and more. While the use of genomics to develop matched therapies for various tumor types has led to groundbreaking treatments such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) and monoclonal antibodies, we have reached a plateau with these targeted therapies and immunotherapies. A comprehensive understanding of the tumor’s molecular landscape is necessary to advance beyond this point.

What Advances Can We Expect in the Next Decade?

The future promises a shift away from the monotherapy, one-size-fits-all approach to more personalized treatments that incorporate real-time sequencing, real-time drug delivery, and combination therapies tailored to individual patient profiles across multiple dimensions.

The good news is that ongoing research is focused on identifying novel targets, developing new agents, and understanding resistance mechanisms to existing therapies. This will pave the way for new personalized treatments and the ability to target previously “undruggable” targets such as KRAS, MYC, and P53. Over the next decade, we anticipate a significant rise in the use of antibody-drug conjugates, bispecific antibodies, radiopharmaceuticals, proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs), CRISPR-based therapies, and other treatments specifically designed to address unique molecular pathways and underpinnings of cancer.

Designing Clinical Trials

Another challenge is the need for robust clinical evidence to support the use of precision oncology approaches, which requires well-designed clinical trials and comprehensive data collection.

Adaptive trial designs such as basket or umbrella trials allow for simultaneous testing of multiple therapies or targets within a single study, increasing the efficiency and flexibility of clinical trials. Incorporating biomarker-driven patient selection and real-time data monitoring can also enhance trial success rates and accelerate the development of effective treatments. Another option is N-of-1 studies in which a single patient is evaluated and serves as their own control.

But clinical trial design is just one part of the equation, clinical trial access must also be considered. The inclusion of a diverse patient population is necessary to ensure the generalizability of trial results and to address disparities in clinical research.

Role of AI

The 2024 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to John J. Hopfield, PhD, and Geoffrey E. Hinton, PhD, for pioneering work in machine learning through artificial neural networks. In Chemistry, David Baker, PhD, received half the award for advances in computational protein design, while Demis Hassabis, PhD, and John Jumper, PhD, shared the other half for breakthroughs in predicting protein structures. These achievements, rooted in artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, are set to transform precision oncology.

Today, we have access to an abundance of health care data from clinical trials, genomic studies, imaging studies, and epidemiological research. However, this data often remains siloed within its respective domains, making it nearly impossible for humans to analyze the vast spectrum comprehensively. Fortunately, we are entering an era of AI and machine learning. These technologies will significantly enhance our ability to interpret complex genomic data, predict treatment responses, identify actionable mutations and biomarkers for novel targeted therapies, and uncover patterns of response and resistance mechanisms, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Additionally, digital health tools including electronic health records and telemedicine are facilitating the integration of genomic data into clinical practice and patient monitoring. However, there is still work to do in the standardization of genomic testing and data integration to ensure the benefits of these technologies can not only be incorporated into routine care but will also become widely accessible.

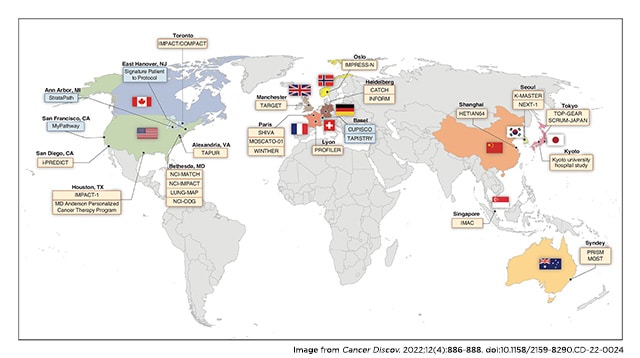

This will require continued innovation and real-time collaboration among technology developers, clinicians, policymakers, regulators, and payers. Globally, it will also mean improving health care infrastructure in some countries to ensure that genomic testing and advanced treatments are available to wider, diverse populations.

Expanding precision oncology Access Globally

Democratizing access to advances in both technology and medicine will also require global harmonization across regulatory bodies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and its equivalents around the world. For the most part, we have seen access to precision oncology drugs confined to both the sides of the Atlantic, with countries like Australia and Japan only recently added to the list. That means something like two-thirds of the world lack access to precision medicines, so we need to think globally and act locally.

For example, in the United States, the FDA has already made significant progress with initiatives like the accelerated approval pathway and tissue-agnostic drug development in oncology. These programs provide many patients, especially those with rare cancers, access to precision medicines. But how can similar programs be implemented in other countries? And how can we collaborate with local policymakers to ensure that more precision medicines are available globally?

Additionally, we need more effective methods for data sharing and conducting post-marketing surveillance across countries. This will undoubtedly be a challenge over the next decade, requiring increased collaboration between regulatory bodies, industry, and the academic community. Such efforts are essential to create a more agile and responsive regulatory environment worldwide.

Developing a Genomically Savvy Workforce

Both locally and globally, there is a pressing need for comprehensive training for health care teams, particularly at the physician level, to ensure they are well versed in genomic medicine and its applications. The pace of education for oncologists has not kept up with the rapid evolution of genomics and targeted therapies. Increasing genomic literacy among health care providers will also enhance their ability to explain these therapies to patients, which is crucial for facilitating informed decision-making by both parties.

Genomically savvy physicians and health care teams can also help bridge gaps in health care disparities by raising awareness of genomic testing and related therapies or clinical trials, particularly among underserved populations. By addressing these challenges and leveraging technological advances with a multistakeholder, all-hands-on-deck approach, we can move closer to a world where precision oncology and personalized cancer treatment become a reality for all.

Vivek Subbiah, MD, is a medical oncologist, clinical trialist, and precision oncology advocate. He is the chief of early-phase drug development at Sarah Cannon Research Institute (SCRI). He manages SCRI’s nine drug development units and expands early-phase programs across its network of over 1,300 physicians in 24 states. Subbiah has been principal investigator in over 150 phase I/II trials and co-investigator in over 250 clinical trials, contributing to drug approvals for over 15 indications worldwide. An expert in tumor-agnostic precision oncology, he led BRAF and RET studies to FDA approval and has over 400 peer-reviewed publications. He is also active on social media @VivekSubbiah and hosts the JAMA Oncology podcast.