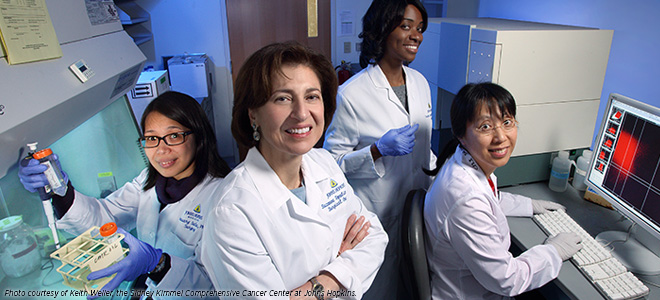

Dr. Suzanne L. Topalian: Developing Cancer Immunotherapy

Dr. Suzanne L. Topalian of the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins is working to find new ways to unleash the power of patients’ immune systems to fight their cancers.

Cancer immunotherapy research holds the promise to fundamentally change the way a number of types of cancer are treated.

But what is immunotherapy? Why are people so excited about this cutting-edge area of cancer research? And how could it impact the care of you or your loved one?

Cancer immunotherapy refers to treatments that harness the power of patients’ own immune systems to fight their cancers. The excitement surrounding these revolutionary treatments stems from the fact that several forms of cancer immunotherapy have yielded dramatic and long-lasting responses for some patients with various forms of the disease.

For example, some patients with metastatic melanoma – a disease that historically has very poor outcomes, with most patients living less than a year after diagnosis of metastases – are reported to be cancer-free 10 years after starting treatment with the cancer immunotherapy ipilimumab (Yervoy).

Despite the potential, however, a limited number of cancer immunotherapies are currently available. Most of those are used to treat melanoma and kidney cancer. Moreover, only a small percentage of patients receiving these treatments have dramatic and long-lasting responses.

Suzanne L. Topalian, MD, professor of surgery and oncology and director of the Melanoma Program at the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, and her team, are working to deliver the promise of cancer immunotherapy to many more people.

The physician-scientist’s research focuses on two approaches to using the immune system to fight cancer – releasing a brake on the immune system called PD-1 and devising therapeutic vaccines that will trigger cancer-killing immune cells to act.

“Decades of basic research at the bench have brought us to the point we are at today, where we are beginning to devise effective ways to increase the activity of the immune system against cancer,” says Dr. Topalian. “One of the things we have learned is that cancers put up special defenses to thwart an immune attack, and my work concentrates on strategies that are designed to overcome this tumor immune suppression.”

Releasing a Brake on the Immune System

Everyone has a cadre of immune cells called T cells that are potentially capable of destroying cancer cells. They are the same cells that help us ward off disease-causing microbes such as the flu virus and bacterial infections such as strep throat.

In many patients with cancer, the tumor engages “brakes” on the T cells, preventing them from fighting the cancers. Dr. Topalian and her team are involved in the clinical development of a new class of cancer immunotherapies that work to release a T-cell brake called PD-1.

One study conducted by Dr. Topalian and her colleagues in this area was reported in Clinical Cancer Research, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. In assessing long-term outcomes for three patients from the first clinical trial of a PD-1-targeted cancer immunotherapy called nivolumab, the researchers found that the patients – one with colorectal cancer, one with renal cell cancer, and one with melanoma – were still benefiting from the immunotherapy three years later.

“There is a rapidly growing list of cancer types for which releasing the PD-1 brake has been reported to benefit patients,” says Dr. Topalian. “However, clinical trials are lengthy, time consuming, and expensive to conduct, and we need to find a way to identify in the lab which cancer types are most likely to respond so that we can prioritize their testing in the clinic.”

To overcome this hurdle Dr. Topalian and other cancer researchers are seeking to analyze samples obtained from patients before they begin treatment with a PD-1-targeted cancer immunotherapy.

Using this approach, she and her colleagues recently reported in another

Clinical Cancer Research paper the identity of a potential marker for predicting whether a cancer will respond to nivolumab treatment, but she says that more needs to be done because using multiple markers may be even more accurate.

“Markers of response to these treatments will not only help identify which cancer types clinical testing should concentrate on but may also help select individual patients most likely to benefit from these treatments,” Dr. Topalian says.

Boosting the Immune System

Enhancing the ability of T cells to eliminate cancer cells can be achieved by an approach to immunotherapy that has been likened to stepping on a car’s accelerator. There are a number of strategies to doing this, and Dr. Topalian’s research focus is on understanding how best to trigger melanoma-killing T cells to act while they are still inside the patient’s body.

One form of cancer immunotherapies that work in this way is called therapeutic vaccines, and effective therapeutic vaccines have traditionally been hard to develop. Dr. Topalian is conducting innovative lab-based research to understand how to create successful melanoma therapeutic vaccines and the optimal way to use them.

One idea that she is testing in the lab is combining therapeutic vaccines with PD-1-targeted cancer immunotherapies to give cancer-fighting T cells a double shot – a push on the accelerator and a release of a brake.

“There are so many possible combinations of cancer immunotherapies,” says Dr. Topalian. “Our preclinical research will help us choose the best options for testing in the clinic. It may be that the best combinations will be different for different cancer types, and preclinical research will allow us to test this out.”