New Cancer Therapies Approved in U.S.

The FDA recently approved new therapeutics for acute lymphoblastic leukemia, metastatic melanoma, and advanced ovarian cancer.

In December 2014, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued three approvals for new medications to treat several aggressive types of cancer. Decades of basic biomedical research lay the foundation for the development of new cancer therapeutics.

The FDA’s recent decisions demonstrate continued progress against the more than 200 diseases we call cancer and highlight the promise of cancer immunotherapy, which seeks to harness a patient’s own immune system to fight their disease, and personalized cancer medicine, which uses our growing understanding of cancer genetics to develop new treatments.

The newly approved therapeutics provide new approaches to treat certain patients with:

- Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), a form of leukemia that is less common among adults than children, but more deadly for adults.

- Metastatic melanoma, a disease that is projected to kill almost 10,000 U.S. residents in 2015.

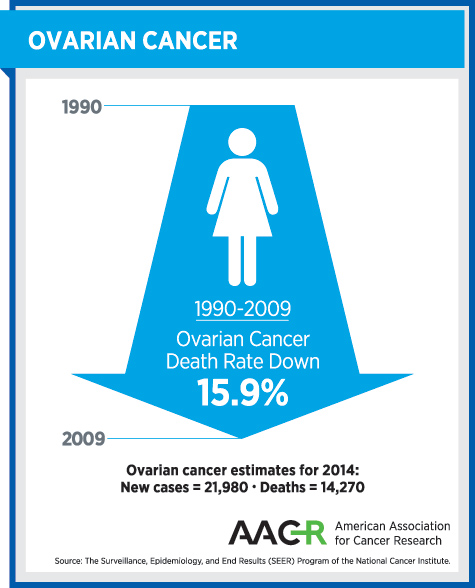

- Advanced ovarian cancer, which accounts for 60 percent of diagnoses of this form of cancer and has a 27 percent 5-year survival rate.

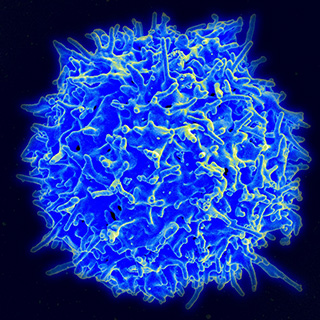

Cancer immunotherapy is the collective term for treatments that harness the power of a patient’s own immune system to fight their cancer. Several of these groundbreaking treatments have yielded dramatic and long-lasting responses for some patients with a number of types of cancer, and they hold the promise to transform outcomes for patients with other forms of the disease.

Two of the cancer treatments approved by the FDA in December 2014 were cancer immunotherapeutics. Both were approved several months earlier than expected, adding to the excitement surrounding the field of cancer immunotherapy.

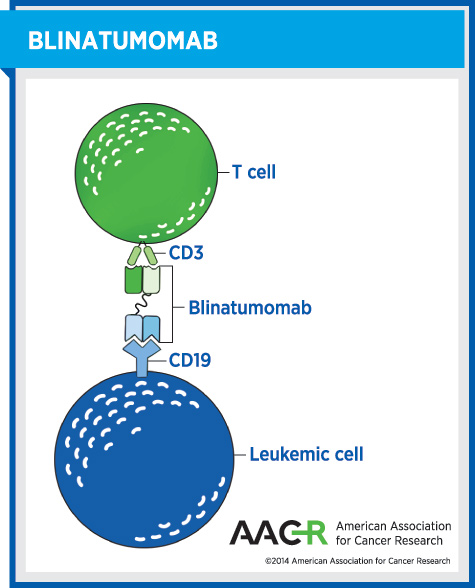

Blinatumomab (Blincyto), was approved for treating certain patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Specifically, it was approved for adults with relapsed or refractory precursor B-cell ALL without the Philadelphia chromosome.

Although this is a rare form of cancer – fewer than 2,250 U.S. adults are projected to receive a precursor B-cell ALL diagnosis in 2014 – patients with this aggressive disease have a dismal outlook. The median survival is between two and eight months, and there is an urgent need for new treatment options.

The second cancer immunotherapeutic to receive an FDA approval in December 2014 was nivolumab (Opdivo).

Nivolumab was approved for treating patients with metastatic or unresectable melanoma who are no longer responding to other drugs. It is the second in a class of cancer immunotherapeutics called PD-1 inhibitors to receive approval from the FDA for the treatment of this condition. The first member of this class, pembrolizumab, was approved a few months earlier in September 2014.

The 2014 FDA approvals of pembrolizumab and nivolumab are helping transform the treatment landscape for melanoma, a disease projected to kill almost 10,000 U.S. residents in 2015.

Moreover, these cancer immunotherapeutics are showing promise in clinical trials as potential treatments for other types of cancer, including non-small cell lung cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma, and renal cell carcinoma. It is hoped that there will be a string of new FDA approvals for groundbreaking immunotherapy agents to treat other forms of cancer in the near future.

A third new cancer treatment to be approved by the FDA in December 2014 was a

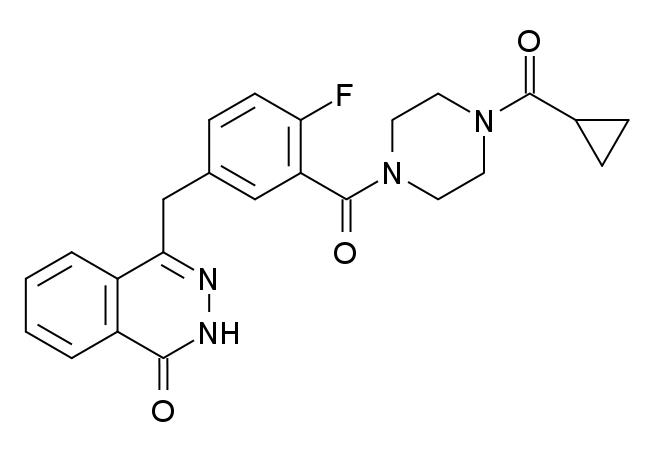

personalized cancer medicine called olaparib (Lynparza).

This FDA decision will impact a subgroup of patients with advanced ovarian cancer – those who have already been treated with three or more types of chemotherapy and who have a deleterious or suspected deleterious germline BRCA mutation, as detected by a test called BRACAnalysis CDx, which was approved by the FDA at the same time as olaparib.

Prior to the approval of olapraib, there were no personalized cancer medicines approved for treating women with ovarian cancer. Progress against the disease was urgently needed, as highlighted by the fact that more than 60 percent of ovarian cancers are diagnosed at an advanced stage, for which the five-year survival rate is just 27 percent.

Olaparib is the first in a new class of personalized cancer medicines called poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors. It exerts its anticancer activity, at least in part, by blocking the DNA repair function of PARP proteins, which can ultimately trigger cell death.

There are several pathways that can trigger repair of damaged DNA in addition to the base excision repair pathway in which PARP proteins play a role. One of these pathways involves the proteins BRCA1 and BRCA2, and BRCA gene mutations that disable this pathway are estimated to be present in about 15 percent of ovarian cancers diagnosed in the United States. Preclinical studies have shown that cancer cells with one DNA repair pathway out of action as a result of a BRCA mutation are particularly susceptible to blocking of the base excision repair pathway using a PARP inhibitor, and these studies provided much of the rationale for the clinical testing of olaparib.

The three new cancer treatments approved by the FDA in the final month of 2014, as well as the approvals that are expected in the coming months, illustrate the continuous progress we are making against cancer.

However, it is imperative that we accelerate the pace of progress because it is anticipated that cancer will be the cause of death for 589,430 U.S. residents in 2015, and this number is predicted to dramatically increase in the coming decades without new preventive interventions and treatments.