Targeting Tumors Based on a Biomarker

The FDA’s new approval for the immunotherapeutic pembrolizumab is the first based entirely on a tumor biomarker rather than the site where the cancer originated.

We have reached a milestone in oncology: The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently announced the first approval of an anticancer therapeutic for use based on the tumor having certain biomarkers and not where in the body the tumor originated.

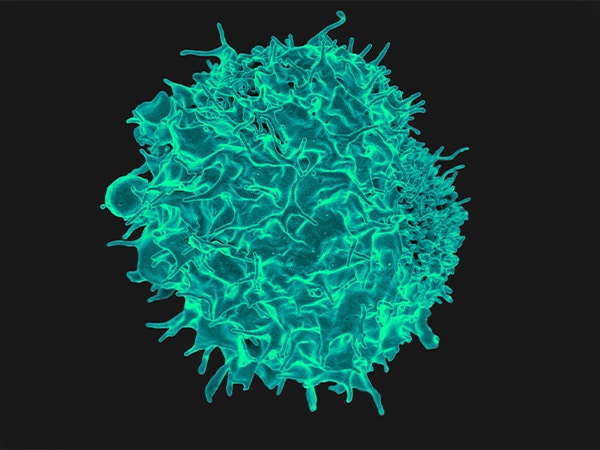

The approval of the immunotherapeutic pembrolizumab (Keytruda) – an immune checkpoint inhibitor that works by releasing a brake called PD-1 on cancer-fighting T cells – is for the treatment of certain adults and children who have unresectable or metastatic solid tumors found to be microsatellite instability-high or mismatch repair-deficient, including those who have microsatellite instability-high or mismatch repair-deficient colorectal cancer.

Pembrolizumab and other immune checkpoint inhibitors have been approved by the FDA to treat various forms of cancer from melanoma and lung cancer to Hodgkin lymphoma and bladder cancer among others. Until this latest approval, each approval was for use in the treatment of a specific type of cancer, as defined by the location in the body where the tumor originated.

The approval pembrolizumab to treat a tumor based on the presence of a biomarker is a major shift away from the traditional approach of approving anticancer therapeutics based on cancer type. In this case, pembrolizumab was specifically approved for those patients whose tumors have progressed despite prior treatment and who have no satisfactory alternative treatment options.

Maintaining DNA integrity is essential for a cell to remain healthy. The integrity of DNA is constantly under threat from errors that arise during cell multiplication or because of exposure to certain chemicals and ultraviolet radiation from the sun. If DNA is not appropriately repaired, mutations accumulate, increasing the chance that a cell will become cancerous. Thus, cells have several interrelated pathways that they use to repair damaged DNA.

Mutations in genes encoding proteins involved in one of these pathways, the DNA mismatch-repair pathway, can result in cells acquiring the microsatellite instability-high characteristic. Mismatch repair-deficiency and microsatellite instability are found in both hereditary and sporadic cancers arising at several anatomic locations, including the colon, endometrium, stomach, and rectum.

In the case of colorectal cancer, it is estimated that about 15 percent of all cases diagnosed in the United States are microsatellite instability-high because of a DNA mismatch repair-deficiency. A significant proportion of these cases occur in individuals with Lynch syndrome, an inherited disorder caused by inherited mutations in DNA mismatch repair pathway genes that significantly increases a person’s risk of developing certain types of cancer, in particular colorectal cancer.

Numerous lines of research have led to the idea that cancers with a high mutational burden are more likely to be responsive to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Given that cancers with a mismatch repair-deficiency have a high mutational load, researchers set out to test in a clinical trial whether mismatch repair-deficient tumors were more responsive than mismatch repair-proficient tumors to pembrolizumab.

Results from this small study, which were published in The New England Journal of Medicine in 2015, suggested that this was indeed the case. Pembrolizumab treatment resulted in tumor shrinkage for 40 percent of the 10 patients with mismatch repair-deficient colorectal cancer, compared with none of the 18 patients with mismatch repair-proficient colorectal cancers. In addition, five of seven patients with mismatch repair-deficient cancers other than colorectal cancer responded to pembrolizumab treatment.

These data led the FDA to grant breakthrough therapy designation to pembrolizumab for the treatment of patients with microsatellite instability-high colorectal cancer in November 2015. This designation is designed to expedite the regulatory assessment of new therapeutics.

According to the FDA, the approval of pembrolizumab for unresectable or metastatic solid tumors found to be microsatellite instability-high or mismatch repair-deficient was based on data from 149 patients with microsatellite instability-high or mismatch repair-deficient cancers enrolled in five small clinical trials. Among these patients, 90 had colorectal cancer and 59 patients had one of 14 other types of cancer, including endometrial cancer, gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer, pancreatic cancer, and biliary cancer.

Pembrolizumab treatment led to tumor shrinkage in 39.6 percent of the patients, with 11 patients having a complete response and 48 a partial response. The percentage of patients who had tumor shrinkage was similar among those with colorectal cancer and those with a different type of cancer: It was 36 percent among the patients with colorectal cancer and 46 percent among the patients with the other 14 types of cancer.

The approval of pembrolizumab for unresectable or metastatic solid tumors found to be microsatellite instability-high or mismatch repair-deficient was based on response data, rather than overall survival data. Thus, the FDA requires Merck, the manufacturer of pembrolizumab, to conduct additional studies to confirm that the immune checkpoint inhibitor improves survival.

Given that recent data from early-stage clinical trials show that pembrolizumab may benefit some patients with gastric cancer and Merck has announced that the FDA would make a decision on this potential use of pembrolizumab by Sept. 22, 2017, it is likely that the number of patients with cancer for whom pembrolizumab is a potential treatment option will continue to rise in the near future.