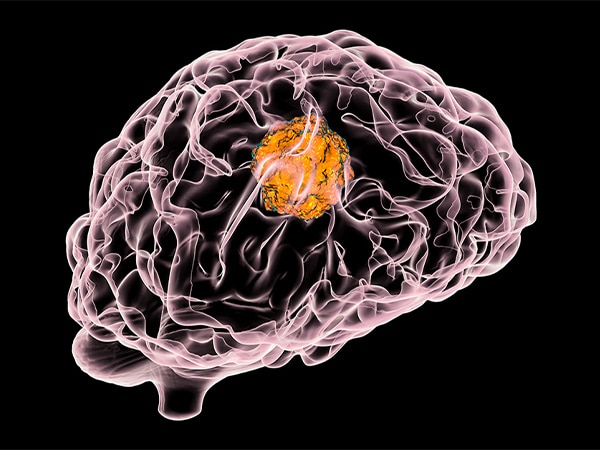

Treating Melanoma Brain Metastases With Immunotherapy

A recent study found that initial treatment with a checkpoint inhibitor was associated with increased median overall survival in patients with melanoma which spread to the brain.

Incidence of melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer, is on the rise in the United States. Federal statistics estimate that more than 95,000 cases of melanoma will be diagnosed each year in the united states.

And if melanoma metastasizes, it becomes more challenging to treat. This is especially true if melanoma spreads to the brain.

Checkpoint inhibitors, a type of immunotherapy that enables patients’ own immune cells to more effectively attack tumors, are now often used to treat advanced melanoma patients. As of July 2018, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had approved three checkpoint inhibitors for treating advanced melanoma – pembrolizumab (Keytruda), nivolumab (Opdivo), and ipilimumab (Yervoy). The combination of ipilimumab and nivolumab is also approved for this use.

Because many clinical trials often exclude patients that have brain metastases, few patients with melanoma that has spread to the brain were included in the initial clinical trials testing checkpoint inhibitors for melanoma. As a result, the survival benefit of these drugs in patients with melanoma brain metastases has not been determined.

In a recent study published in Cancer Immunology Research, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research, researchers analyzed data from more than 2,000 stage 4 melanoma patients who presented with brain metastases between 2010 and 2015. They determined that the initial treatment of those patients with a checkpoint inhibitor was associated with significant improvement in the median overall survival, up from 5.2 months to 12.4 months. Moreover, the four-year overall survival rate rose from 11.1 percent to 28.1 percent.

For a subset of these patients – those whose cancer had only metastasized to the brain, and not to other parts of the body – the results were even more pronounced. Here, initial treatment with a checkpoint inhibitor was associated with an increase in medial overall survival from 7.7 months to 56.4 months, and the four-year overall survival rate jumped from 16.9 percent to 51.5 percent.

“Historically, most approaches to treating CNS [central nervous system] metastases from melanoma as well as other solid tumor types have provided minimal benefit for patients,” said study author David A. Reardon, MD, clinical director of the Center for Neuro-Oncology at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. “The results of our analyses indicate that immune checkpoint inhibitors can achieve a meaningful therapeutic benefit for metastatic melanoma including spread to the CNS. At the same time, not all patients benefit, indicating that much research is still required to optimize the potential of anti-tumor immune responses for CNS metastatic disease.

The authors also found that patients with certain characteristics – such as being younger, having fewer comorbidities, and being insured privately or through Medicare (versus no insurance at all), among other reasons – were more likely to receive treatment with a checkpoint inhibitor.

Senior author Timothy Smith, MD, PhD, MPH, director of the Computational Neuroscience Outcomes Center at the Department of Neurosurgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School, added: “Through the use of nationwide cancer data, for the first time we can evaluate the impacts on survival that these exciting new therapies have for patients with melanoma brain metastases, highlighting the power of population data to help answer critical, but previously unanswerable, questions that we face every day in clinical practice.”