Why Doesn’t Immunotherapy Benefit Everyone?

Researchers are seeking to understand why some patients do not respond to immunotherapeutics and to identify ways to ensure more get the benefits of these exciting new cancer treatments.

Immunotherapy is dramatically changing the prospects for many patients with a growing number of different types of cancer. But what about those patients whose cancers do not respond to immunotherapeutics, and those whose cancers respond initially but then progress after becoming resistant to the treatments –

Identifying ways to extend the benefits of immunotherapy to these individuals has become the focus of many cancer researchers. A recent study sheds light on potential ways to overcome current limitations.

What is the Problem?

There have been many stories of success with immunotherapy. Take the story of Philip Prichard of Memphis, Tennessee, who was diagnosed with advanced kidney cancer in 2012. When his cancer returned and was found to be inoperable, Philip enrolled in a clinical trial testing the immunotherapeutic nivolumab (Opdivo).

After three months Philip’s tumor had shrunk by 30 percent.

“The quality of my life improved monthly,” he said. “I could feel myself getting stronger, I started to gain weight, I was able to get back to work, and [my wife] Susan and I were able to travel again.”

Nivolumab is among a class of immunotherapeutics known as checkpoint inhibitors. Initially approved for patients with melanoma, these immunotherapeutics have since been approved for the treatment of patients with lung cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma, bladder cancer, kidney cancer, and head and neck cancer.

Some patients treated with checkpoint inhibitors such as nivolumab experience long-lasting or durable responses, and these success stories are certainly cause for excitement.

For example, the results of a clinical trial showed that more than one in three patients (34 percent) with metastatic melanoma were still alive five years after starting treatment with nivolumab. But that also means two-thirds of the trial participants had tumors that did not respond to those treatments or progressed after initially responding.

How Can We Help Nonresponders?

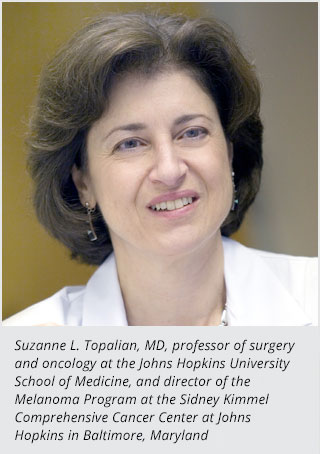

A recent study published in the AACR journal Cancer Immunology Research reports on efforts by Suzanne L. Topalian, MD, professor of surgery and oncology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and director of the Melanoma Program at the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center in Baltimore, Maryland, to address the issue of nonresponse to checkpoint inhibitors targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 brake on T cells .

“Between 15 and 30 percent of patients with renal cell carcinoma, the most common type of kidney cancer, have substantial and durable responses to immunotherapeutics that target the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, such as nivolumab,” said Dr. Topalian, who is also associate director of the Bloomberg-Kimmel Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy at Johns Hopkins. “Researchers are now trying to identify markers that can predict whether or not a patient is likely to respond to these treatments, so that those who are unlikely to respond are saved the time and can avoid the potential adverse effects of a treatment unlikely to benefit them.”

Dr. Topalian explained that some prior studies suggest that renal cell carcinomas positive for PD-L1 are more likely to respond to PD-1 pathway blockers compared to those negative for PD-L1, but that not all PD-L1-positive renal cell carcinomas respond to these immunotherapies.

As a result, she and her colleagues focused their analysis on archived pretreatment tumor samples from 13 patients with metastatic kidney cancer positive for PD-L1 who had gone on to receive nivolumab through clinical trials. Four of these patients were classified as having responded to nivolumab treatment and nine were classified as having not responded.

They identified 110 genes that were expressed at significantly elevated levels in tumors from nonresponding patients and found that many of these genes were associated with metabolism, the chemical processes that generate energy and eliminate waste products in cells.

“If these data are reproduced in larger groups of patients, we could potentially use the information to guide treatment decisions for patients with renal cell carcinoma,” said Dr. Topalian.

She also noted that the researchers are looking to extend these studies to analyze other types of cancer, as well as to confirm the current results in additional renal cell carcinomas from patients receiving anti-PD-1 therapies.

“Such studies may also reveal new drug targets for combination therapies with anti-PD-1,” Dr. Topalian added.