How Can We Reduce the Risk for Esophageal Cancer?

Cancer of the esophagus, a relatively rare cancer, is a diagnosis that approximately 18,440 Americans are expected to receive in 2020. A look at the incidence and mortality charts from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database shows that the rates have been steady for the past two decades. One potential step toward progress is raising awareness; April is esophageal cancer awareness month.

Esophageal cancer is relatively difficult to diagnose. If caught early, which happens in less than 20 percent of patients, the five-year survival rate is about 46.7 percent. For the roughly 40 percent of patients who are diagnosed when the disease has spread, five-year survival is a dismal 4.8 percent.

Who gets esophageal cancer?

Esophageal cancer is more common in men than in women. Esophageal adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma are the most common types of esophageal cancer. More people are diagnosed with esophageal adenocarcinoma each year than squamous cell carcinoma. Black men and women are more likely to be diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus than whites. While esophagoscopy, biopsy, brush cytology, and few other tests are often used to detect esophageal cancer, there are no standard or routine tests to screen for this disease.

As with most other cancers, the chance of developing esophageal cancer increases with age. In addition to age, major risk factors for esophageal cancer include smoking, heavy alcohol use, and a diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus.

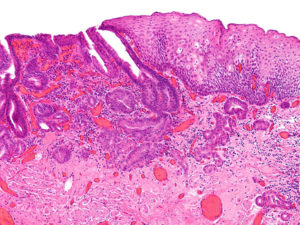

Barrett’s esophagus, a precursor to esophageal adenocarcinoma, progresses through gradual changes in the lining of the esophageal epithelium. These changes occur through stages defined as low-grade and high-grade dysplasia. Research has shown that the risk for esophageal adenocarcinoma in those with Barrett’s esophagus is increased by 11-fold; however, only 0.12 percent of those with Barrett’s esophagus are likely to be diagnosed with esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a known risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma, and patients with GERD are more often screened for Barrett’s esophagus through endoscopy than those without GERD. A new device called Cytosponge was recently tested to detect Barrett’s esophagus. Read about it in Cancer Today.

A study published recently in the AACR journal Cancer Prevention Research that compared patients with Barrett’s esophagus and controls with and without GERD noted that when stratified for GERD symptoms, the associations of other risk factors, including demographic, clinical, and lifestyle factors, with Barrett esophagus did not change, suggesting that a combination of risk factors should be considered in developing individualized esophageal cancer screening efforts for patients with Barrett’s esophagus.

In a recent study published in another AACR journal, Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, researchers identified certain genetic variants that may increase the risk for esophageal cancer. In this meta-analysis, data from 304 publications that included 104,904 cases and 159,797 controls were examined to study the association between 95 variants in 70 genes or loci and the risk for esophageal cancer. The study found 13 variants in or near 13 genes, including CDKN1A, CHEK2, CYP1A1, EGF, PTEN, and PTGS2, that were associated with susceptibility to esophageal cancer. The authors note these findings could lay the groundwork for the identification of novel genetic factors that play a role in esophageal cancer and for the development of screening and prevention strategies for clinical management.

What influences the progression of Barrett’s esophagus to esophageal cancer?

In a study published in Scientific Reports last month, researchers examined the risk factors associated with the progression of Barrett’s esophagus to dysplasia and esophageal adenocarcinoma. They analyzed clinical, epidemiologic, endoscopic, and histologic factors, and found that age, abdominal obesity, smoking, colonic adenomas, and caffeine intake increased the risk.

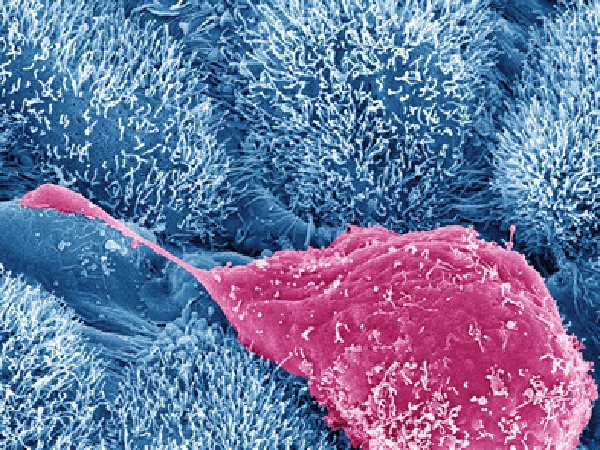

In another study, which was published in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention last year, a team of researchers conducted a case-control study in patients with and without Barrett’s esophagus who were scheduled to undergo upper endoscopy. Esophageal brushings were collected from controls and cases with low-grade or high-grade dysplasia or esophageal adenocarcinoma.

The study found no difference in the bacterial diversity between non-Barrett’s esophagus and Barrett’s esophagus, but the diversity was decreased in patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma. Further, there was a shift in the composition of the bacteria from low-grade dysplasia to high-grade dysplasia. Patients with high-grade dysplasia and esophageal adenocarcinoma were found to have relatively increased abundance of Enterobacteriaceae, a family of bacteria known to play a role in the inflammation of the gut and in carcinogenesis. The researchers conclude that the microbiome may play a role in the progression of the precursors of esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Can esophageal cancer be prevented?

One way to potentially prevent esophageal cancer is to avoid risky behaviors, such as smoking, and heavy drinking. A recent study found that physical activity plays a role in preventing many types of cancer, including esophageal cancer. There is some evidence that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can provide protection against squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus.

In the study from Scientific Reports discussed above, the researchers found selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor drugs (SSRI) provided protection against neoplastic progression of Barrett’s esophagus. The authors note that SSRIs are known to reduce cancer cell viability, suppress cell division, and slow tumor growth in preclinical studies of colorectal cancer, and that some of these mechanisms may also play a role in preventing the progression of precursors of esophageal adenocarcinoma.

The study also found that statins reduced the progression of precursors to high-grade dysplasia or esophageal adenocarcinoma by 48 percent. Research suggests that statins provide this protection via their antiproliferative, antiangiogenic, and proapoptotic effects.

The Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention study cited above that described the potential role of the microbiome in the progression of precursors of esophageal adenocarcinoma also found that compared with subjects not taking proton pump inhibitors, those taking this medication had increased gram-positive Streptococcus bacteria, which are known to have beneficial effects, and decreased gram-negative bacteria overall, which are known to have harmful effects, including promoting chronic inflammation. The authors note that the utility of proton pump inhibitors would require further study.

What progress has been made against this disease?

Research fuels progress against all cancers, including esophageal cancer.

Based on data from two clinical trials, KEYNOTE 180 and KEYNOTE 181, in 2019, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the use of the immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab (Keytruda) to treat some patients with advanced esophageal cancer. Specifically, the treatment was approved for patients with locally advanced or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus that has progressed after treatment with one or more lines of standard therapy. Eligible patients must have the protein PD-L1 in their tumors. The FDA also approved the use of the PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx test as a companion diagnostic for this indication.

A path forward

As researchers continue to learn more about the various factors that promote esophageal cancer, we can expect to see more progress with prevention, early detection, and treatment for this disease.