Understanding Inherited Breast Cancer

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in the United States. In 2018, 266,120 women and 2,550 men are expected to receive the news that they have the disease, according to National Cancer Institute data.

Inherited mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes account for between 5 percent and 10 percent of breast cancers in U.S. women and between 5 percent and 20 percent of breast cancers in U.S. men. For women who undergo genetic testing and learn that they have inherited a BRCA1/2 mutation before they receive a breast cancer diagnosis there are ways to reduce their risk of going on to develop the disease. Unfortunately, researchers estimate that most women with an inherited BRCA1/2 mutation cannot take advantage of breast cancer risk–reducing measures because they do not know they carry the mutation.

That’s why October, which is Breast Cancer Awareness Month, is a good time to raise awareness of the role that heredity plays in breast cancer and to highlight recent research published in Nature that holds promise for helping people who undergo genetic testing for BRCA1 mutations to better understand the significance of the results they receive.

As we provide insight into the issue of inherited breast cancer risk, it is important to remember that most cases of breast cancer are not caused by inherited genetic mutations but are caused by mutations that a person acquires during their lifetime.

Inherited genetic mutations can increase breast cancer risk

Researchers estimate that inherited genetic mutations account for between 5 and 10 percent to as many as 27 percent of all breast cancers. Inherited mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes account for many of the cases. However, some are accounted for by mutations in other genes, including PALB2, TP53, PTEN, CDH1, and STK11. For example, one study found that 10.7 percent of 488 patients with breast cancer had an inherited mutation in one of the 25 cancer-susceptibility genes studied: 6.1 percent in BRCA1/2 and 4.6 percent in 10 other genes.

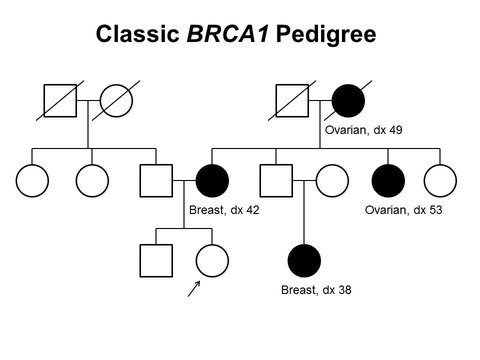

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are the most extensively studied breast cancer–susceptibility genes. Certain mutations in these genes not only increase risk for breast cancer, but also increase risk for ovarian, pancreatic, and prostate cancers. These mutations are often referred to as deleterious or harmful mutations to distinguish them from benign mutations in these genes that do not affect BRCA1/2 function and/or do not increase risk for cancer.

Women with a harmful BRCA1/2 mutation are up to seven times more likely to get breast cancer and 30 times more likely to get ovarian cancer before age 70 than average-risk women, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. To put this in context, an average-risk woman in the U.S. has about a 12 percent and 1.3 percent chance of being diagnosed with breast cancer and ovarian cancer, respectively, at some point during her lifetime.

Women who learn that they have inherited a harmful BRCA1/2 mutation should consult their health care practitioners because there are several ways that they can substantially reduce their risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer. Some women choose an enhanced breast cancer screening plan that may include screening at a younger age, at more frequent intervals, and/or using additional technologies such as MRI. Some choose to take tamoxifen or raloxifene, which are endocrine therapeutics that have been shown to reduce the incidence of invasive breast cancer by 30 percent to 68 percent in clinical trials that included women with various levels of risk for the disease, not just women with an inherited harmful BRCA1/2 mutation. Others choose risk-reducing surgery; it has been shown that having a bilateral mastectomy can reduce breast cancer risk by 85 percent to 100 percent and having a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy can reduce breast cancer risk by 37 percent to 100 percent and ovarian cancer risk by 69 percent to 100 percent.

Despite having ways to decrease cancer risk for women who have inherited a harmful BRCA1/2 mutation, it has been estimated that 90 percent of currently cancer-free individuals in the United States who have one of these mutations do not know it. Even among living breast cancer patients, only 30 percent of those with a harmful BRCA1/2 mutation have been identified.

BRCA1/2 genetic testing

Even though harmful BRCA1/2 mutations can dramatically increase a woman’s risk for breast cancer, these mutations are relative rare; it is estimated that just 1 in 400 people in the general U.S. population carry a harmful BRCA1/2 mutation. Therefore, most experts, including the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, recommend that a woman consider BRCA1/2 testing only if her health care provider deems it appropriate based on detailed assessment of her personal and family history.

As with all medical procedures, there are pros and cons to undergoing BRCA1/2 testing. For example, a positive result can empower a woman to act to reduce her risk of breast and ovarian cancer while a negative result can provide a sense of relief. On the other hand, a positive result can lead to anxiety and depression.

A less talked-about downside of BRCA1/2 testing is that the result of the test may be ambiguous because it reveals that there is a mutation in either the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene but we do not know whether or not the mutation increases risk for cancer. These mutations are known as variants of unknown significance (VUS). It has been reported that from 5 percent to 6 percent of BRCA1/2 tests among individuals of European ancestry in the United States show a VUS. Among individuals of African-American ancestry, VUS results are reported for up to 21 percent of tests. Determining whether BRCA1/2 VUS are inconsequential or important in increasing cancer risk is an area of intensive research investigation. One recent paper provides new insight into the likely clinical significance of hundreds of BRCA1 VUS.

Improving understanding of BRCA1 VUS

In the new paper, a team of researchers used a relatively new technology that they call saturation genome editing to assess the effect of nearly 4,000 single–base pair variations in the BRCA1 gene in an in vitro assay. This technology involves using the CRISPR–Cas9 gene editing tool to mutate each base pair in the DNA region being studied into every other possible base pair, one at a time.

The team focused on 13 of the 22 BRCA1 coding exons, selecting those that encode regions of the BRCA1 protein known to have an important role in the tumor suppressor function of the protein.

After in vitro analysis of the effects of each of 3,893 BRCA1 single–base pair variations, the researchers classed each variation as functional, nonfunctional, or intermediate. They then looked at how well their function data correlated with clinical significance data for the single–base pair variants found in the ClinVar database, a public archive of the clinical significance of genetic variants identified in patient samples that is funded by the National Institute for Health. Most of the 169 single–base pair variants classed as harmful in ClinVar were nonfunctional in the researchers’ assay and most of the 22 variants classed as benign in ClinVar were functional. They also classed 25 percent of the single–base pair VUS in ClinVar as nonfunctional.

The researchers, who are making the data freely available online to nonprofit, noncommercial users, said in a press release that they hope that “… the database will continue to grow and will become a central point for guiding the interpretation of actionable variants as they are first observed in women.” However, Stephen J. Chanock, MD, director of the National Cancer Institute’s Division of Cancer Epidemiology & Genetics cautions in a commentary accompanying the research paper that even though it might be tempting to make immediate use of the assay to interpret VUS identified during human genetic testing, in vitro data alone should not be used as the basis for medical advice—at least until the approach has been clinically validated.

Notwithstanding the cautionary remark, Chanock ends his commentary on a high note, stating that the study should help researchers to realize the promise of precision medicine.

Thank you for sharing this thorough post and individuals must be aware that this is hereditary so they can go for genetic testing.