Upcoming FDA-AACR Workshop Will Discuss DPD Deficiency Testing

When the chemotherapy drug 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) was approved in 1962, there was limited understanding of how it is metabolized by the body. What was clear, however, was its efficacy against cancer. Today, 5-FU and a related drug called capecitabine are commonly used in cancer treatment, but we now know that rare genetic variants can increase the likelihood that patients will experience severe, potentially life-threatening or fatal, toxicities.

Given the serious implications, should all patients be tested for these genetic variants prior to receiving 5-FU or capecitabine, even if it delays potentially life-saving treatment? How should patients be tested? Are the available tests reliable?

These important questions, among others, will be explored at an upcoming workshop organized by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR).

The FDA-AACR workshop, To Test or Not to Test—That is the Question: DPD Deficiency and Weighing Potential Harms, will be held on January 16, 2025, in Bethesda, MD, as well as online for those wishing to attend virtually. Registration is free and open to the public.

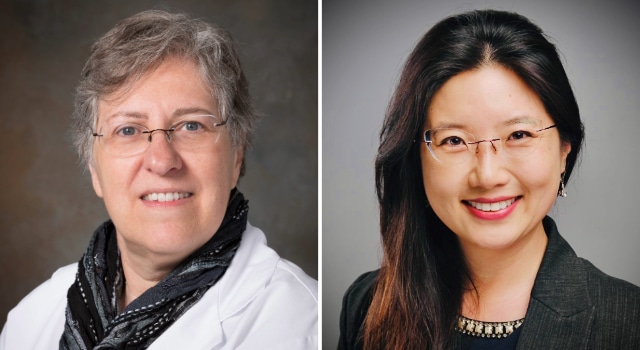

We spoke with the workshop’s cochairs—AACR President Patricia M. LoRusso, DO, PhD (hc), FAACR, from Yale Cancer Center, and Jennifer Gao, MD, from the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence (OCE)—to learn about the considerations for DPD deficiency testing and how the workshop aims to address some of the outstanding questions in the field.

What is DPD deficiency?

Gao: 5-FU and capecitabine are part of a group of chemotherapy agents known as “fluoropyrimidines.” Both of these drugs have been widely used as part of the standard of care treatment for patients with several cancers for many decades, including cancers in early stages where treatment is given with curative intent; 5-FU was approved by the FDA in 1962, and capecitabine was approved in 1998.

When 5-FU or capecitabine is given to patients for the treatment of their cancers, the body processes these drugs to a form that reduces the growth of cancer cells and to other forms that are not toxic so that the body can dispose of them. Some patients may have a rare inherited condition where their body is not able to properly break down these drugs, known as a dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD) deficiency.

The gene DPYD gives the body directions to make the DPD enzyme, and this enzyme plays an important role in eliminating fluoropyrimidines from the body. In some patients, one or both copies of the DPYD gene harbor certain variants that reduce activity of the DPD enzyme, and in very rare cases, the DPD enzyme may be rendered completely inactive. Patients with certain variations in the DPYD gene may have varying degrees of reduced activity of the DPD enzyme depending on the type and number of variants present and whether variants are found on one or both copies of the DPYD gene.

Decreased DPD activity can increase the likelihood of severe side effects, with the severity differing from patient to patient. The most frequently seen side effects include mucositis (sores of the mouth, tongue, throat, and esophagus), diarrhea, neutropenia (low white blood cell counts), and neurotoxicity (nervous system problems); these side effects can be severe or even life-threatening in patients who have DPD deficiency and are also receiving fluoropyrimidine drugs.

What are the benefits and harms of DPD genetic testing?

LoRusso: The benefit of testing, of course, is that we could potentially identify patients at risk of serious or life-threatening toxicities from 5-FU and capecitabine so their treatment can be adjusted accordingly by either choosing an alternative chemotherapy agent or by modifying the fluoropyrimidine dose. However, not all DPD deficiency testing is equal. There is not a standardized companion diagnostic test for this purpose, so the results of testing can be variable depending on many factors, such as gene variants tested, which tests are used, and other considerations.

There are also logistical concerns with cost and timing to consider. There are scenarios where a patient cannot wait for the test results to come back, especially if the test has to be sent out to a commercial lab and the patient urgently needs to start treatment.

Gao: It is important that tests provide accurate results and that prescribers have clear recommendations to follow. Test accuracy is critical, and currently there are no FDA-cleared or approved tests that can accurately identify patients with a DPD deficiency. Uncertainty related to potential false positive or negative results is challenging both for patients who have a DPD deficiency that may not be detected, and for patients who do not have a DPD deficiency but may end up delaying or foregoing potentially curative treatment based on inaccurate test results.

In addition, since there are many variations of DPD deficiency, a positive or negative test result will not necessarily predict what side effects a patient may experience or how severe they will be. There is also limited information on what dose of 5-FU or capecitabine would be safe if the test results show partial DPD deficiency, and what the differences in efficacy may be at reduced fluoropyrimidine doses.

What information is currently included in the FDA-approved labeling for 5-FU and capecitabine on DPD deficiency?

Gao: The approved product labels for both 5-FU and capecitabine include information about the risks of serious adverse reactions from DPD deficiency in multiple sections and in the “Patient Information” document. The labeling informs prescribers that treatment should be discontinued in patients who exhibit acute early-onset or severe reactions, and that testing before treatment should be considered if the patient’s clinical status permits. Additionally, both the 5-FU and capecitabine labeling states these drugs are not recommended for use in patients known to have certain homozygous or compound heterozygous DPYD variants that result in complete DPD deficiency.

What is the main objective of the workshop?

LoRusso: The workshop aims to bring together experts from all fields—clinicians, researchers, advocates, and others—to discuss the very important topic of genetic testing for DPD deficiency and how it should be handled moving forward. The workshop’s main objective is to expand education and awareness of the issue, which will ultimately impact clinical decision-making.

The workshop is currently shaping up in such a way that it should be relevant and informative for a wide range of audiences. I’m hoping that the attendance will include educators, people interested in science and pharmacogenomics, clinicians, advocacy groups that can educate patients, and patient advocates themselves who can help us better understand what the needs are from a patient and caregiver perspective.

Gao: The workshop will discuss the complicated issues surrounding DPD deficiency testing. We hope attendees will better understand what is presently known about DPD deficiency and the available tests, clinical considerations for counseling and testing patients prior to starting cancer treatment with 5-FU or capecitabine, potential implications of universally testing all patients, and future directions, including how drug companies, device industries, government agencies, patients, and oncology health care providers can all work together to advance the field and continue improving the safety of patients receiving 5-FU and capecitabine for their cancer treatment.

How will the collaboration between AACR and FDA strengthen the workshop?

LoRusso: Together, the FDA and AACR bring multiple angles to the workshop that would not be possible with either in isolation. The FDA embodies expertise on patient safety, patient drug tolerability, and drug therapies, while the AACR brings with it a vast scientific body of knowledge created by the membership that it holds. Through this membership, AACR will be able to widely disseminate the discussions that come out of the workshop about the value of DPD testing, the consequences of testing vs. not testing, who should be tested, and other topics.

Gao: The FDA OCE and the AACR share a common goal of providing greater awareness, understanding, education, and communication on this very important topic which impacts many patients with cancer undergoing treatment. Through a joint workshop, the OCE and AACR will leverage their combined expertise and convene a multidisciplinary panel to collaborate and advance the field of DPD deficiency awareness, testing, and knowledge. We look forward to a productive and meaningful discussion, and we hope to see many of you in person and online on January 16, 2025.